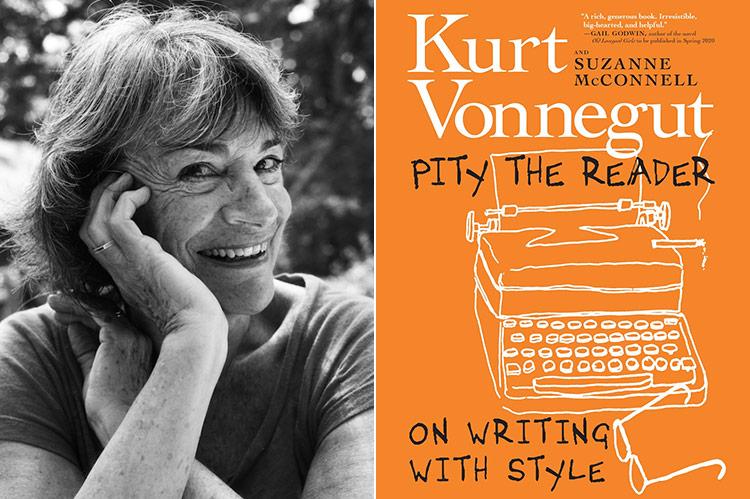

“Pity the Reader”

Suzanne McConnell

Seven Stories Press, $32.95

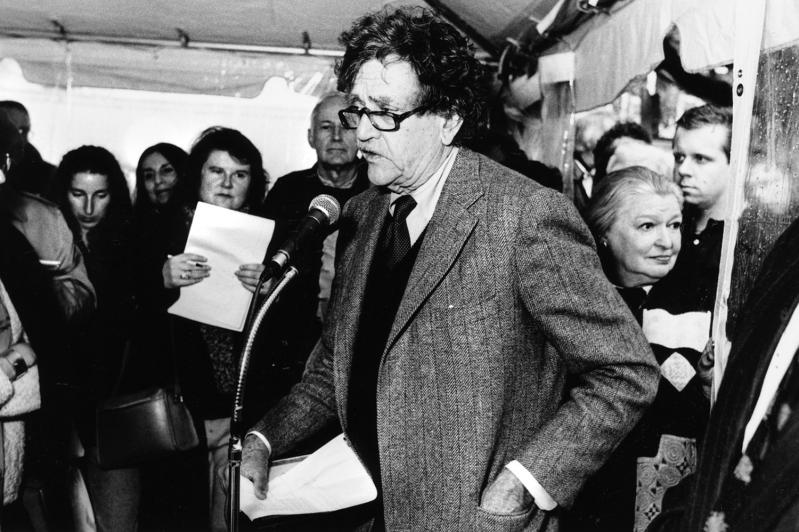

In 1965, broke with three children, Kurt Vonnegut took a teaching post at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He was far from a famous writer then, his first two books already out of print. Vonnegut claimed that the head of the writing program, Paul Engle, “hadn’t even heard of me.” But then they needed a last-minute replacement for Robert Lowell, who’d “decided not to appear.”

Among his students at Iowa were the novelist John Irving, Gail Godwin, and the author and editor Suzanne McConnell, who subsequently taught writing at Hunter College for three decades. In the new book “Pity the Reader: On Writing With Style,” Ms. McConnell has assembled a compendium of essentially everything Kurt Vonnegut ever said or wrote about being a writer. These teachings — most of them pragmatic, if occasionally didactic — are presented along with entertaining biographical anecdotes, edited manuscript pages from Vonnegut’s novels, and personal remembrances from Ms. McConnell’s days as his student.

Taken as a whole, “Pity the Reader” is generous, encouraging, and nothing if not thorough, checking in at roughly 400 pages (by the end Ms. McConnell is even instructing on how to be married to, and married as, a writer). As a fiction writer’s chapbook, it is best taken in small chunks, where in brief chapters, with titles such “Beginnings,” “Breakthrough,” and “Plot,” to name a few, Ms. McConnell uses Vonnegut’s comments as a jumping-off point to address the budding writer’s most basic concerns.

The advice is mostly useful, and a bit familiar. “Have the guts to cut,” implores Vonnegut. “Every character should want something,” he says later on, “even if it’s just a glass of water.” Ms. McConnell warns of one of her failed early stories about a toxic love affair: “Too much attachment to my personal experience. Not enough distance.”

This last comment also relates to Vonnegut’s struggles with his early attempts at the novel that was to become “Slaughterhouse-Five.” In perhaps the strongest section of the book, Ms. McConnell marks the evolution of that novel all the way back to letters Vonnegut wrote to his family during World War II. There are exclamations of frustration, bits of misfired first drafts, all culminating with the breakthrough — the mordant, ironic first-person voice he finally discovered in the late 1960s. Asked in 1969 how it felt to finally have a great success with “Slaughterhouse-Five,” Vonnegut replied with typical crusty humility.

“I would hate to tell you what this lousy little book cost me in money and anxiety and time. When I got home from the Second World War twenty-three years ago, I thought it would be easy for me to write about the destruction of Dresden, since all I would have to do would be to report what I had seen.”

“I had to say something about it,” he concludes in an earlier interview. “And it took me a long time and it was painful.” For any author who has ever struggled with a difficult novel, these words function both as a caveat and a catharsis. If you’re on to something big, it will probably hurt.

Not everything here is a pearl of wisdom, however. Ms. McConnell begins the book with a 1980 article Vonnegut wrote for The New York Times titled “How to Write With Style.” She quotes a number of “rules” from his piece, which include “Do not ramble,” “Keep it simple,” “Say what you mean to say,” and, finally, “Pity the readers.” While these are solid edicts for a freshman composition class, we can be thankful that authors as baroque as Melville, Faulkner, and Pynchon never heeded them. David Foster Wallace’s 1996 masterpiece, “Infinite Jest,” for example (it’s essentially one long digression), clocks in at just over a thousand pages, printed in a font so small you need a radio telescope to discern it. How’s that for pity?

No, not everyone is David Foster Wallace, but then that is the point. Rules as ascribed to writing — especially fiction writing — are a folly. It has been done 10,000 different ways, and will yet be done 10,000 more. The only tried-and-true rule is “be great,” which is nearly impossible, and precisely why it is so thrilling the rare times we encounter it.

Later in the book, in fact, Ms. McConnell will take her teacher to task for his tendency for what she calls “methodologism.” And in the classroom, “Pity the Reader” chronicles a wiser, more hands-off Vonnegut. John Irving recalls him this way: “He’d say, ‘This part bored me.’ And then one hundred pages later he’d say, ‘This was really funny. . . .’ Mostly he just left me alone.”

The writer Barry Jay Kaplan remembers his first conference with Vonnegut: “ ‘Your stories make me very nervous. . . . I don’t know what to say about them.’ ” A “silence ensues,” until Vonnegut adds, “ ‘What I mean is . . . I just think you ought to keep writing them, don’t you?’ ”

And it may be that Ms. McConnell has the sagest advice of all in “Pity the Reader.” “Be kind to yourself,” she advises. “Don’t pummel yourself with expectation. Go easy. Your material will eventually find its way to voice.”

Perhaps this, in the end, is all that a creative writing “instructor” can really offer: gentle encouragement. Ms. McConnell nearly admits as much. “If you’ve got some talent, passion, and a good story to tell, must you spend a fortune on an MFA program to hone your craft?” she asks. “Not necessarily.”

A young writer could do worse, however, than “Pity the Reader,” which is instructive but mostly restrained and, for Vonnegut fans, an incidental portrait of one of the 20th century’s great American satirists.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of “Lit Life,” among other novels. He lives in Springs. Kurt Vonnegut lived in Sagaponack.

Suzanne McConnell will talk about “Pity the Reader” at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor on Saturday at 5 p.m.