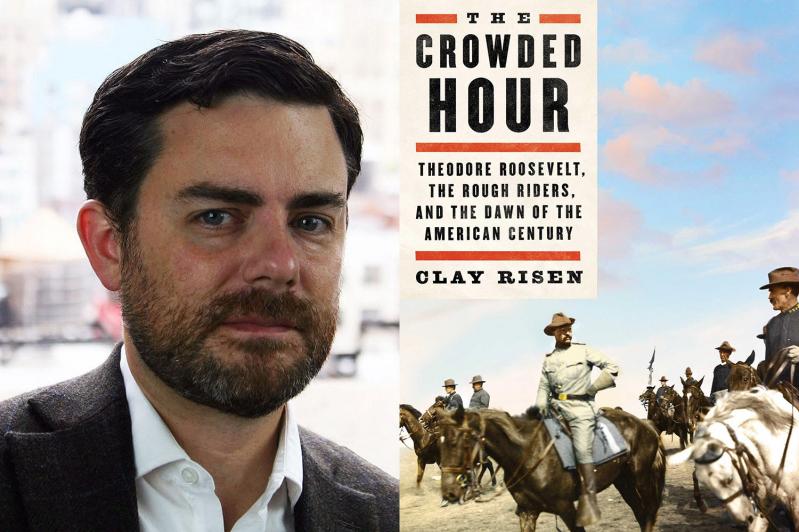

“The Crowded Hour”

Clay Risen

Scribner, $30

We denizens of the South Fork are perhaps aware that the great T.R. and his Rough Riders were encamped at Montauk following the victory of San Juan Heights in Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898. Actually, after five days of quarantine with his men, Theodore Roosevelt came and went from New York City and his home in Oyster Bay, but his regiment remained there for a time in case they should be needed to finish off the battle for Cuba.

Such is the local interest of Clay Risen’s engaging narrative in “The Crowded Hour,” which, while telling the story of Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, is primarily concerned with this event as the turning point in America’s role in the larger world.

Mr. Risen’s title is taken from Roosevelt’s own account in “The Rough Riders,” published by Scribner’s in 1899, in which he describes the onset of the assault: “The instant I received the order I sprang on my horse and then my ‘crowded hour’ began.”

You can almost feel T.R.’s characteristic exuberance in these words. “Bully!” he would often say to express his excitement.

The casus belli of this adventure was the Cubans’ stalemated struggle for independence from Spain, which had decimated the country, a failed American diplomatic effort to broker a settlement, alarming reports of humanitarian horrors promulgated by Hearst and Pulitzer newspapers, and then, notoriously, the sinking of the battleship the Maine. Mr. Risen’s objective, though, is not simply to retell the story of Cuba, T.R., and the Rough Riders, but to show when and how the United States began “playing with the great forces that . . . shape the future of the world,” as The Atlantic magazine put it at the time, and to suggest connections between that historical moment and the present.

The central chapters of the book make up a page-turning account of the Rough Riders’ ordeals and victory over the Spanish in 1898, which resulted in a treaty granting the United States “temporary” control of Cuba and ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

This story is framed by an account of the political moment when this country turned away from an inward-facing century of continental expansion and economic development to one of outward action, and the author identifies this transformation directly with T.R.’s personality: “Cuba represented a perfect test, and opportunity, for America as an emergent world power — intervention would be ‘as righteous as it would be advantageous,’ ” he writes, quoting Roosevelt.

T.R.’s valet, Edward Marshall (an African-American cavalry veteran), later wrote that Roosevelt seemed suddenly changed by the heat of battle into “the most magnificent soldier I have ever seen.” Thus, Roosevelt’s crowded hour became America’s crowded hour.

Teddy Roosevelt most probably knew that phrase from Sir Walter Scott’s classic novel “Old Mortality,” in which a chapter is headed by verse (attributed by Scott to an anonymous poet writing in the 18th century, now identified as Thomas Osbert Mordaunt) that says much about the national mood at this moment in American history:

Sound, sound the clarion, fill the fife,

To all the sensual world proclaim,

One crowded hour of glorious life

Is worth an age without a name.

Mr. Risen’s opinion of the new American tendency to interventionism is cautionary, if not critical. For example, he writes: “A brash rising nation like America, one that was asserting its newfound power abroad arrayed in the cloak of liberty and humanitarianism, could not have found a better enemy [Spain] — both as a caricature to match its own self-mythologizing, and as a declining empire . . . reveal[ing] the artifice that underlay the oncoming American century.”

Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders came to define America’s vision of itself as the heroic champion of those who seek liberty and independence: “On paper, the battle [of San Juan Heights] paled in every way to the major engagements of the Civil War.” And yet the battle “remains among the most important, celebrated, and contested engagements in American history.”

The takeaway from Mr. Risen’s argument is that “this pattern of ‘intervene first, ask questions later’ became a template for American foreign policy in the twentieth century.”

The title, the verse, and its attitude say it all. “Bully!” T.R. would have exclaimed.

Ana Daniel is the special projects editor for The Southampton Review. She lives in Bridgehampton.

Clay Risen is the deputy op-ed editor at The New York Times.