A 1947 Painting, Newly Cleaned, Reveals Pollock's Methods

The cleaning of “Alchemy,” one of Jackson Pollock’s earliest poured paintings, has revealed a new depth of color and contributed further evidence that his working methods included using a structural plan as a way to ground his poured compositions.

The popular belief is that the artist’s application of paint was arbitrary, that “he threw stuff on the canvas and that was it,” according to Helen Harrison, the director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs. In fact, she said, although Pollock’s working methods were improvisational, “there is a plan, a grid of sorts that serves as a foundational armature or structure that he would play off against the next layers of paint.”

“Alchemy,” painted in 1947, was part of the original Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, a public art institution started by the art dealer and early patron of American Abstract Expressionists such as Pollock, as well as avant-garde European artists. She lived in New York City during and after World War II and was briefly married to Max Ernst, but returned to Europe a few years later, after her collection was featured in the Venice Biennale of 1948, and bought a Venetian palazzo.

Until recently, nothing had been done to “Alchemy” — the name came from an East Hampton neighbor, Ralph Manheim — since it went to Venice, said Ms. Harrison. The canvas “had never been cleaned or lined.” This was unusual, she said, as conservators have a tendency to tinker with works of art in order to strengthen them, clean them, or otherwise address issues of concern. “This painting was pristine in that way, but it was very dirty, and that made it dull. When a painting like that is cleaned properly it comes to life.”

“Alchemy” is also unusual in that it has a very dense and layered surface, which makes it fragile, so much so that it has never even left Venice, except for the trip to Florence for the cleaning. “Once they took off the grime, you could see that the colors really are true‚” and they carry through the different layers of the complex painting, said Ms. Harrison.

The difference is so dramatic that the Peggy Guggenheim Collection is hosting a special exhibition through September to celebrate the cleaning. It features the painting, shown without protective glazing to offer the full revelation of its surface. As part of the process, the conservators commissioned a three-dimensional scan of the painting and made a sculptural replica of it; visitors can touch the replica’s surface to fully appreciate the depth of the paint Pollock applied to the canvas. (A video of the scan is available here.) The scan also reveals what type of paint was used where, and the velocity with which it was applied.

Ms. Harrison said the scan offered such a thorough analysis of “Alchemy” that when a chip fell off the painting, the model was able to pinpoint the exact spot it had fallen from.

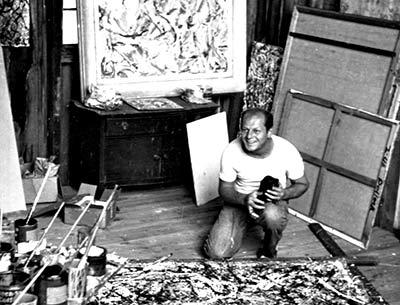

Pollock’s house and studio on Springs-Fireplace Road became involved in the Guggenheim exhibition after Luciano Pensabene Buemi, its co-curator, visited here with a curatorial team, to see where the artist painted.

From photographs taken at the time, it was obvious where on the studio floor “Alchemy” had been placed. Pollock laid out his largest canvases on an east-to-west axis, according to Ms. Harrison, so that the northern light would be behind him while he worked, but smaller canvases such as “Alchemy” could have been laid out anywhere on the floor.

The photographs showed the painting stretched on an old quilting frame that had belonged to Pollock’s mother. In a very timely coincidence, part of the frame was recently found, during the restoration of Pollock’s garage. “It still has the paint from ‘Alchemy’ on it,” Ms. Harrison said.

The frame is now on view in Venice as part of the exhibition, along with some of the paint cans from Pollock’s studio through September.