The Family Business

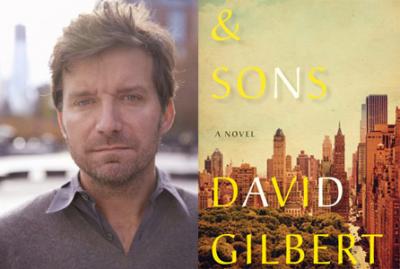

“& Sons”

David Gilbert

Random House, $27

Add David Gilbert’s “& Sons” to the short list of this year’s best novels. Mr. Gilbert’s foot is on the gas from the very beginning of this ambitious, chance-taking novel and he never lets it up. He brilliantly balances a multilayered story of familial relationships and lifelong friendships and breathes new and exciting life into what can be the too familiar stories of father-son relationships and of writers and the tribulations of the writing life.

At the forefront of a large assortment of characters is A.N. Dyer, a frail, reclusive 79-year-old legendary writer best known for his first novel, “Ampersand,” for which he won the Pulitzer Prize at the age of 28. In ill health, he asks his two older, estranged sons, Richard and Jamie, to return to New York City in order to know their much younger half-brother, Andy, better. Only 17, Andy’s birth was the result of an affair Dyer had with a young woman who “shined her youth against my darkening age.” Her unexpected death brought their infant son to the father to be raised, resulting in his wife, Isabel, divorcing him.

The novel opens at the funeral of Dyer’s lifelong best friend, Charles Henry Topping. Topping’s youngest son, Philip, a failed writer, is the story’s curious narrator. Recently separated from his wife and children because of an extramarital affair, he has also lost his teaching position at a private school (where he once was Andy’s teacher). He has an “infatuation” with Dyer, “the great man.”

Philip ingratiates himself into the Dyer orbit, although Richard and Jamie barely tolerate him at best. He is both an outlier and interloper. He feels an emotional attachment to Dyer and longs for even the most contemptuous recognition from him. He thinks he would be a better son to him than Dyer’s own are: “I knew I could be a good son, the right son, the proper son to this great man, certainly better than his real sons.”

While thinking of how little he actually knew about his own father, a man he once told his mother he did not love, Philip observes that “fathers start as gods and end as myths and in between whatever human form they take can be calamitous for their sons.” The in-between period certainly causes problems for the Dyers.

Dyer believes his choosing to be a writer was a detriment to his being a real father to his sons. It gave him an excuse to withdraw from family life and indulge himself. His removal from their lives made him a mystery to them while growing up. Jamie thinks he knows his father better through reading his novels than through his own personal relationship with him, but he recognizes that “being a good and attentive father was neither in his nature nor in his nurture.” Dyer’s stated goal as a father was Hippocratic, to do no harm, but he tells his sons they should sue for malpractice.

While Dyer may not be father of the year, his sons have not won any prizes either. When his own son, Emmett, asks him why he hates his father, Richard honestly replies that “neither one of us was suited to the relationship” and admits that he would have hated any father. Richard and his father share the certainty that death would resolve many of their problems. Richard says that only when Dyer is dead will he be able to love him without complication, while Dyer thinks that he can “only be a good father to a dead son.”

Dyer’s considerable fame is borne not only by him but also by his sons, for both good and ill. Studio heads, headmasters, sycophants, and honest admirers all use the sons as a means of attempting to reach their reclusive father. However, his fame can also reflect upon them advantageously: “Maybe A. N. Dyer was a cold and distant light but he gave them a shine they parlayed into a swagger.”

Dyer hopes to mitigate his mistakes with his older sons through his relationship with Andy. He sees Andy as a means to rewrite the errors in his own life, just as he is rewriting the draft of his famous first novel and improving it as he does. (It is part of a scheme to secure a better price from the Morgan Library, which wants to buy his papers. Unbeknownst to anyone, he burned the original draft of “Ampersand” long ago.) He calls rewriting the draft a “reconstruction project,” and Andy is quite literally his own personal reconstruction project, especially if we are to believe a bizarre midnovel plot twist.

The father refers to his youngest son as “my best days ahead.” He tells his oldest sons that he wants his last words to be: “Be kind. Rewind.” Evoking the ubiquitous video store slogan, Dyer yearns to return to the beginning and be granted a do-over.

Despite his fame, or perhaps because of it, writing made Dyer a miserable person. He claims that imagining the stories is the best part of the writing process. The actual writing, however, is like Chernobyl. He finds no joy in the work, just relief that the disappointment is manageable. He proclaims the process a parody of living.

Despite their efforts to distance themselves from their father, Richard, a former drug addict, now drug counselor and screenwriter, and Jamie, a film documentarian, find themselves in the family business. They all struggle to create substitute worlds that call into doubt the gaps between life and art, fiction and reality, and that raise the question in what ways are our lives true.

This question is central for Philip, the ersatz writer and erratic narrator, as well as displaced son and father. Through his discovery of some old correspondence between his father and Dyer (which is reproduced throughout the book), he comes to a realization about his father that fuels a desire for revenge upon the Dyers for his father and himself.

Philip is telling his story through a prism of 12 years, looking back at the time of his father’s death and the return of the elder Dyer sons. Philip is not only a vengeance-minded narrator but apparently an omniscient one as well, imagining much of what he could not possibly know. He tries to “refashion his father” from the correspondence and “all the bits of information, both in fact and in fiction,” he uncovers or divines.

Philip’s version of the story of A.N. Dyer and his sons is his own opportunity to rewind and reimagine what happened. How much can the reader accept as true, especially once Philip acknowledges, “I’m not sure what really happened”? But even if it is fiction, does it tell the truth?

Mr. Gilbert stakes out large topics — family, friendship, literature, creativity, and death among them. He brings the kitchen sink to the novel, almost as if he believes “& Sons” may be his one and only chance so he might as well crank up the novelistic machinery to overdrive and use all of the tricks he can. Yet he integrates all of the elements into an intricate and coherent whole.

There might be some complaint about an excessive number of characters or too many plotlines, rambling digressions, or simply too many pages, but Mr. Gilbert weaves the threads together masterfully. Any complaint seems minor compared to what he achieves. Mr. Gilbert is a gifted writer of exceptional insight, imagination, and control. “& Sons” is a beautifully written virtuoso work — both tragic and comic — from beginning to end.

William Roberson taught literature at Southampton College for many years and now works at L.I.U. Post.

David Gilbert lives in Southampton and New York.