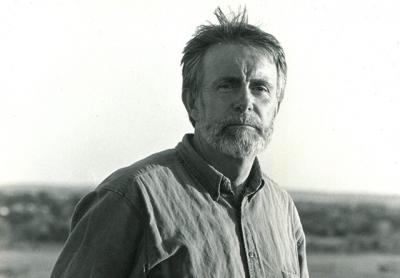

Gary Reiswig, Writer, Innkeeper, Was 76

Gary Dwayne Reiswig, the longtime owner and restorer of two of East Hampton’s historical inns, died in his New York City apartment on Aug. 20 with his family at his side. He was 76, and had been diagnosed with prostate cancer three and a half years ago.

Born in Booker, Tex., on Dec. 12, 1939, to John Fred Reiswig and the former Bella Gregory, he grew up on a farm in Beaver, Okla., on the Oklahoma panhandle.

“Grandmother helped my mother give birth,” Mr. Reiswig told an audience at the Parrish Art Museum in 2014, as part of a series the Parrish runs for authors and artists. The Dust Bowl years were ending as he was growing up, but life in Oklahoma, where the family farmed cattle and grain, was still not easy, he recalled. As a child, he would play in his own pretend farm, using old license plates as barns and shiny stones as cows and horses.

His mother, who had been taken out of school in the eighth grade, wanted more for her three children. “She took us to piano and voice lessons,” Mr. Reiswig, who was a strong baritone, told the Parrish audience. She also took them to the library.

Gary Reiswig was bright, and a good athlete, playing baseball and football. Colleges offered him athletic scholarships, but it was the church, central to the family’s farm life, that called to him. Members of his Christian faith saw his potential as a minister. Not only did the church offer a road out of the panhandle, “It chose him,” his wife, Rita Reiswig, said.

He was ordained, and, with his first wife, Patsy McDaniel, moved farther east with every new assignment. They had three children before divorcing in 1970.

Mr. Reiswig’s last ministerial assignment took him to Pittsburgh, where, his wife said, he began losing faith in his calling. “Religion couldn’t really answer all the problems that people had in their lives,” she said. “They needed other types of help, other than God. He gradually left the church.” He returned to school, obtaining a Ph.D. in education from the University of Pittsburgh.

Using the same strengths that made him a good preacher, he turned next to community activism. The needs of the poor and working class for day care and housing became central to his life.

Pittsburgh, like other American cities in the ’70s, was crumbling. In its dilapidated old buildings, Mr. Reiswig saw not despair, but hope. He believed in reclaiming and restoring them, and went to work for the city’s Planning Department to make the dream a reality. “I rededicated myself to preservation, saving old houses instead of souls,” he told his Parrish audience.

On one community project, a parent education program, he met the former Rita Mallet. They worked on it together using their respective strengths, his in education and outreach, hers in psychotherapy, and married on July 20, 1973.

A few years later, the couple stayed at a country inn run by a husband and wife, and thought it seemed an attractive way of life. They took out a want ad in Historic Preservation, a national real estate publication, seeking an old inn in a seaside town on the East Coast to buy and run.

They received over 100 responses. The owners of three East Hampton hostelries — the Hedges Inn, the Huntting Inn, and the Maidstone Arms — were among them. The last had been closed for a few years.

“We actually looked at about eight or nine places, up and down the East Coast,” Ms. Reiswig said. “We rented an R.V. and took our then infant child with us.” They chose the Maidstone. With no experience running an inn, they had a steep learning curve, which they embraced.

Morris Weintraub came on board as chef, leaving the Maidstone Club, and ran the restaurant for 12 years while the Reiswigs ran the inn and the bar. Mr. Reiswig’s passion for restoration was a major factor in the Maidstone’s renaissance; he later became a member of the East Hampton Village Design Review Board.

He had had two siblings, David Reiswig and Jane Reiswig De Burgh, both of whom he lost to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, which had claimed his father as well. His father’s family, it seems, had a genetic disposition to the disease. “Of my father’s generation, 10 of 14 siblings died in their 50s, including my dad,” he said at the Parrish. His wife said he thought that, should Alzheimer’s strike him as well, he could at least do things around the property, such as rake the leaves and tend to the grounds.

In 1986, according to a 2012 article by Gina Kolata in The New York Times, he received a call from an aunt, Ester May, who had lost her husband, his uncle, to the disease. She was participating in an Alzheimer’s study, she told him, and blood donations were needed from members of large families that were known carriers. Mr. Reiswig agreed to donate blood.

Nine years later, scientists isolated the gene that leads to early Alzheimer’s. It turned out that its passing from one generation to another was a hit-or-miss proposition. Gary Reiswig was not a carrier, meaning that his children were not either.

After that, he dedicated much of his time to the fight against the disease, working with the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network and writing a book, “The Thousand Mile Stare.”

The Reiswigs sold the Maidstone in 1992. Four years later they embarked on another project, the J. Harper Poor Cottage, nearby on East Hampton’s Main Street. They restored that inn, now known as the Baker House 1650, with the same enthusiasm they had put into the Maidstone. They sold it in 2004.

During those years Mr. Reiswig’s writing career took off. His novel “Water Boy,” published in 1994 by Simon and Schuster, was semiautobiographical, set in the panhandle. Reviewing it in this newspaper, James McCourt called the book a “powerful and dramatic first novel, notable for long stretches of really solid evocation, dramatization, and even reach.”

Mr. Reiswig also wrote screenplays, began reviewing books for The Star, and recently published a collection of short stories, “Land Rush: Stories From the Great Plains.” He was working on a revision of “The Thousand Mile Stare” at his death, and on another piece of non-fiction, a look at the changes in East Hampton since he had arrived. Rita Reiswig said both manuscripts will be completed posthumously.

Four children survive in addition to his wife. They are Gregg and Jeff Reiswig and Lora Reiswig Brown, by his first wife, and Jesse Reiswig. He also leaves two grandsons and two great-grandsons.

The family has suggested donations in Mr. Reiswig’s memory to the DIAN Project, c/o Dr. Randall Bateman, Campus Box 1082, Washington University, 7425 Forsyth Boulevard, St. Louis, Mo. 63105.