Long Island Books: (Not So) Bad Boy

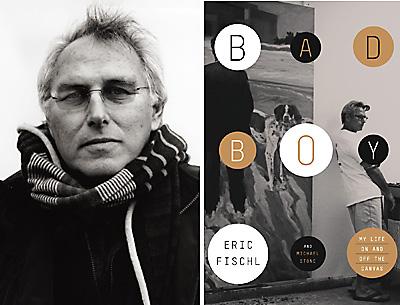

“Bad Boy”

Eric Fischl

Crown, $26

One of the lasting impressions I have of Eric Fischl was a night at the Parrish Art Museum, where he was in discussion with an adjunct curator about Fairfield Porter’s influences. The curator, who is no longer with the museum, had developed an elaborate theory regarding Diego Velasquez’s influence on Porter, an idea at which Mr. Fischl scoffed.

As the talk went on, it seemed that Mr. Fischl was increasingly annoyed by the curator, who, in turn, became more uncomfortable and uncertain. It could have been the moment, the artist’s mood, or the curator’s assumption that he understood painting in a way that gave him the agency to speak for artists and their intentions that riled him, but I walked away with the conclusion that Mr. Fischl was an artist who felt passionately about his work and his understanding of painting and that he did not suffer fools gladly.

In interviews before and after that talk, he was always engaging and apparently sincere. There was no agenda, even when discussing his huge personal project “America: Now and Here,” a mobile multimedia cultural fair that the artist envisioned being set up in temporary locations throughout the country for the exchange of art and ideas in areas that were too remote for them to be engaged in easily. It has yet to be financed.

So, I went into reading “Bad Boy: My Life On and Off the Canvas,” an engrossing and well-written autobiography by Mr. Fischl and Michael Stone, with some mixed impressions of the subject, and now I know why.

Mr. Fischl had a complicated, angry, and sometimes tragic childhood. He grew up with an alcoholic mother, who died after intentionally crashing a Volkswagen minibus into a tree during his college years. Although his mother had some artistic talent, his own was never encouraged. When he found it on his own at a community college in Arizona, his mother was threatened and his father discouraged, concerned that his son needed to find a “real” way to make a living.

Art was always a struggle for him. Although painting came naturally once he discovered his talent, he came of age in a time when at first painting had little value in the art world, and then later his realist style seemed retrograde. His search for subject and style was full of disappointments and challenges, but when he found catharsis in his work by plumbing the depths of his dysfunctional upbringing, he remained true to himself and found success.

He was fortunate to live through one of the more interesting times in American cultural history. He found his way to Haight-Ashbury during the summer of love in 1968 and ended up in the first class at the legendary art school CalArts in Valencia, Calif. It was there that he made two lifelong friends, David Salle and Ross Bleckner. Through the years, Mr. Salle and Julian Schnabel became Mr. Fischl’s main competition, in his eyes, and his ambitions for his work appear to have been shaped by their successes.

What is different and effective in this book is that Mr. Fischl, who is as candid as can be about his own issues and hangups, lets others who played significant roles in his life have their say, even those whom he considered rivals, sometimes bitterly so. Such is the case with Mr. Schnabel, who made it clear he did not want Mr. Fischl to be represented by Mary Boone, Mr. Schnabel’s dealer at the time. When she took him on anyway, he changed galleries, but only after publicly mocking a canvas of Mr. Fischl’s hanging in the gallery.

That was the youthful exuberance of the 1980s. Mr. Schnabel recalls in an essay he wrote for the book that he called Mr. Fischl’s paintings “anemic representations of memories” in a 1987 memoir, but he now says it was unfair. He contrasted his upbringing in tough areas of Brooklyn and Texas with the apparent suburban ennui reflected in Mr. Fischl’s paintings, noting they “didn’t address the violence in my life.” He says he has grown more appreciative of what Mr. Fischl was trying to accomplish. “I was so passionate back then. I took everything personally — the things I loved I stood up for, the things I didn’t, I didn’t.”

Mr. Fischl says in the book that Mr. Salle and Mr. Schnabel were “reintroducing imagery into their paintings, but they were also making art about art. I was trying to make a more direct connection with the viewer. . . . He’d be thinking he shouldn’t look at the stuff I was painting — scenes of masturbation, incest, voyeurism — but he wouldn’t be able to help himself. The only way to get out of the painting was by dealing with it.”

Mr. Fischl and his contemporaries came to maturity in New York, a city that defined success through gallery representation and supercharged sales that catapulted artists from obscurity to fame and wealth in the course of a single show. As a beneficiary of that same attention, Mr. Fischl saw his lifestyle, which included a day job as an art shipper — at one point he needed only $1,000 a month to support himself — change quickly to meals at four-star restaurants that cost about that much.

This monumental shift in the perception of artistic value, so that it correlated with the actual price fetched, changed the art world profoundly in ways we now take for granted.

What remains with the reader after finishing the book is that, despite Mr. Fischl’s high-octane multinational lifestyle and star-studded friendships, he remains supremely humble. After years of learning what it means to paint, studying art history, and then teaching what he has learned to others, beginning in his 20s in Nova Scotia, he has strong opinions about art and states them with great assurance, much like that night at the Parrish. But they are hard won and arrived at through experience and serious soul-searching that bring his self-doubts and insecurities into the mix.

His marriage to April Gornik is also a marvel, as he states himself, as it has survived his drug and alcohol abuse and his art superstardom and then fall. Although that last part, the fall, is hard to reconcile with the continual shows and repeat appearances of his past and current paintings and sculptures in multiple gallery booths at contemporary art fairs throughout the country. He explains that he and Ms. Gornik are the products of similarly difficult childhoods and know how to support each other and give each other distance when necessary.

What I realized in reading “Bad Boy” was that I had my own preconceived notions about what Mr. Fischl was attempting to accomplish in his paintings, but they fell away the more I came to know him through his words. There is a natural distancing that goes on in most art of the past few decades. It is difficult to come to terms in an honest way with someone baring himself figuratively or others literally.

I always assumed a certain ironic detachment and projection in his images of naked men and women in comfortable surroundings. Discovering that his parents lolled about naked at home in front of their four children and his household’s continual exchange of roles between parent and child was like experiencing a painting that at first looks abstract, but is instead an extreme close-up of something very real.

Eric Fischl lives on North Haven.