During the closing of cultural institutions last spring and after, Warren Neidich has emerged as a cultural force of his own. In May, he organized two iterations of "Drive-By-Art," an outdoor public art exhibition that invited artists to exhibit their work on their properties, near roads, or on sidewalks. One, on the South Fork, featured 62 artists; the second, in Los Angeles, showcased 126.

In August, his electronic highway bulletin board appeared outside Guild Hall with two messages: "Artists Are Essential Workers" and "Art Is An Essential Service." When the village of East Hampton determined it was not an artwork, it was removed, only to resurface in Springs at the Leiber Collection and, subsequently, at the Fireplace Project.

And in September, he launched C.A.R.E. Ltd., a studio-cum-gallery in an industrial space off Springs-Fireplace Road that most recently exhibited work by Elena Bajo, Sabra Moon Elliot, Candace Hill, Alice Hope, Laurie Lambrecht, Toni Ross, Bastienne Schmidt, and Almond Zigmund.

While this flurry of activity suggested his recent arrival on the East End, Mr. Neidich in fact has deep roots here. During the 1990s he operated the Nomad Gallery in a potato barn in Sagaponack, executed a project at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, and produced a series of photographs of the horizon at Louse Point for which he placed neuro-ophthalmological instruments in front of his camera lens at the moment of taking the picture.

He was born and brought up in northern Westchester County, but his mother had an apartment in Manhattan. "I always say my greatest art education came when I was in high school just by going to film art houses and museums and galleries," he said during a recent interview from his Los Angeles studio.

He studied photography, video art, psychology, and biology at Washington University in St. Louis, then spent a year as a research fellow studying neuroscience at the California Institute of Technology with Roger Wolcott Sperry, a Nobel Prize winner, before earning a degree in medicine at New York Medical College.

"Washington University had an outstanding art school, and I took all the photography courses I could. But when you're a man, and you have an interest in science, and you do it well, you are pushed into that field." The work he has done throughout his career has brought together ideas from art, science, critical theory, and philosophy.

One of his East Hampton studio works is a neon sign that reads "Cultural Value Transcends Market Value." "I'm a '70s artist, not an '80s artist," he said. "In the '70s, cultural values transcended market values, while in the '80s, market value overwhelmed cultural value." Dennis Oppenheim, Alice Aycock, Nancy Holt, Ana Mendieta, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner are among the artists from that decade he admires.

However, he adds that he is not mirroring the artists of the '70s but trying to update the issues raised by them. The conceptual artists of that decade "were interested in draining all of the sensibility from that artwork to make it a fully cognitive experience. I call those people dry conceptual artists."

"I'm a wet conceptual artist because I want beauty and relevance to be a doorway to enter the work. I am also a 1970s Minimalist in many ways. I have tried to move their phenomenologically based work dependent on sensory experience to one that could be considered post-phenomenological and based on the conceptualizing brain. I engage with the past, but I'm trying to move the discussion in a different direction."

Of the electronic highway sign that debuted at Guild Hall, he said, "It's a '70s work. The sign didn't look like an artwork, but it was." Somebody asked him why he didn't just paint the slogans and hang them on a gallery wall. He cited Smithson, who "took art out of the galleries." That the four walls of the gallery could no longer hold the artwork was an innovation typical of that decade.

Mr. Neidich recently published "The Glossary of Cognitive Activism (For a Not So Distant Future)," in which he defines almost 300 terms related to a political theory called cognitive capitalism, which posits the brain and mind as the new factories of the 21st century. The project was a means of communicating the kinds of words people need to become familiar with "in order that judgments about technology are not the exclusive domain of scientists and investors," but also available to artists and humanists.

He noted that while some neuroscientists still believe in the fixed architecture of the brain, he sides with those who assert that "the socio-political, cultural milieu or environment sculpts the neoplasticity of the brain and its architecture." Scientists have maintained that the gross anatomy of the brain has changed over the last two million years as a result of events -- the discovery of fire, for example -- that happened in the development of human society.

"The big difference today," said Mr. Neidich, "is that we have an accelerated technological field that is directly intervening with the material brain." One consequence of this might be a profound "surveillance nightmare. Not only will your credit card be surveilled when making a purchase, or what you're searching or what you're writing online, but your very thoughts might be monitored." While he envisions that this is where an accelerated technology might be leading us, he understands that these new technologies can also generate emancipating capacities.

Among the many forms his work has taken are multidimensional neon structures, one of which, the "Pizzagate" neon, was recently exhibited at the 2019 Venice Biennial. The result was inspired by fake news, specifically the now-debunked conspiracy theory that Hillary Clinton and some of her aides were operating a child sex ring out of the Comet Ping Pong pizza parlor in Washington, D.C.

Mr. Neidich has noted that the words in the suspended networked structure stand in for both the Cloud and that assortment of functional connections that make up the dynamic brain in action. Specific terms range from "clickbait" to "cognitive capitalism" to "WikiLeaks" to "Edgar Welch," who was so convinced of the story's truth that he traveled from North Carolina to the pizza parlor with an assault rifle. Mr. Neidich also made an experimental video documentary, "Pizzagate: From Rumor to Delusion," for which he received an appreciative letter from Mrs. Clinton.

Another neon piece, "Statisticon," represents the brain as "the central node of an assemblage of new technologies." The words at the top layer of the installation, among them "collage," "actions," "rap," "shamanism," "psychedelic drugs," and "neural plasticity" refer to "the emancipatory capacity of art, and the capacity of nature . . . to open the brain's capacity to be free and liberated rather than controlled and constricted."

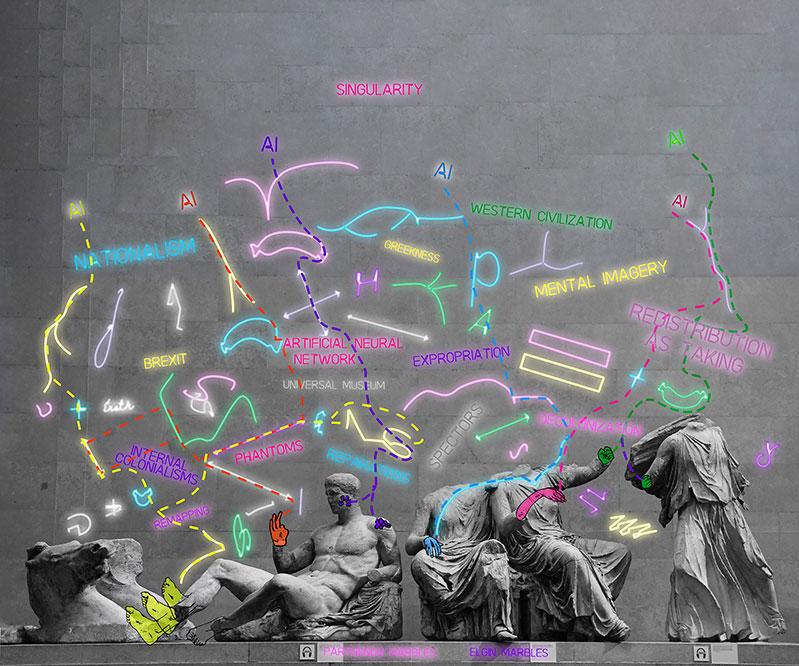

A work currently in progress, "Parthenon Marbles a.k.a. Elgin Marbles Recoded," deals with four sculpted figures that were removed from their original site at the Parthenon in Athens by Thomas Bruce, the Seventh Earl of Elgin, and installed in the British Museum where they now reside. In articulating themes of colonialism and expropriation of indigenous cultural products, Mr. Neidich uses the metaphor of phantom limbs sprouting from the broken limbs of the marble figures to stand in for alternative, non-Western positions on race and gender.

For the past 12 years, before moving to the South Fork during the pandemic, Mr. Neidich has been working primarily in Berlin and Los Angeles. He has taught at Goldsmiths College in London, Weissensee Academy of Art in Berlin, and at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles and has been a visiting lecturer at Brown, Harvard, Columbia, Princeton, U.C.L.A., California Institute of the Arts, La Sorbonne, University of Oxford, and Cambridge University.

His intention, he said, is to "try to incite a new reading of the history of American art that leapfrogs over the '80s, reconnects to the '70s, but in a way that is experimental and up to date with the new kinds of technologies and that can generate new kinds of capacities."