Driving back from the dump one day, I turned down Floyd Street and noticed a cute little house with a “For Sale” sign in front, noting it was under contract. Curious about its price, I looked it up and discovered it had been the residence of the “renowned children’s author and illustrator Marian Foster Curtiss.”

Looking her up, I realized I had spoken about her during a talk I gave in Wainscott many years ago. Besides her career as a children’s book author and illustrator, I recalled her unusual living situation. She spent many summers in Wainscott living in a children’s playhouse.

Finding a summer rental in the Hamptons has never been easy, but a tiny children’s playhouse was most unusual. Life magazine featured Curtiss in a 1952 article, photographing her in the playhouse, where she spent summers for a mere $50 for the season. A Life image portrayed her landlord, Dayton Hedges (1905-1989), towering in the doorframe of the child-size house while she sat at a small table amid her dolls, with watercolor doll sketches pinned to the playhouse walls.

She started coming to Wainscott in 1945. The playhouse, long gone, was located behind the historic Conklin House on Main Street. Her accommodations included a full-size cot, a chair, and a small two-burner kerosene stove. Dayton Hedges ran the Conklin House as a boarding house at the time.

In the late 1960s, Curtiss moved from the playhouse to larger accommodations on Floyd Street in East Hampton. Comparing working and writing in New York City to doing so in the country, Curtiss said in a 1969 interview with The East Hampton Star, “It’s easier to work in the city where the noise is so impersonal . . . here if you hear a car horn it might mean someone is driving into your driveway. . . . Here there is always the ocean beckoning, or digging in the garden.”

I grew up on Oakview Highway, a stone’s throw from Floyd Street. The childhood memory of Floyd Street that stuck with me was of a power company lineman electrocuted while servicing a pole there. My sister, thankfully, had a better memory. She recalled her favorite doll, Tiny Thumbelina, released in 1960. Her doll was damaged, and our mother told her it could be fixed by a doll doctor. My sister was amazed that such a person existed. They arrived at — you guessed it — the little house on Floyd Street, where Marian Foster Curtiss repaired her doll. The experience left an indelible impression on my sister.

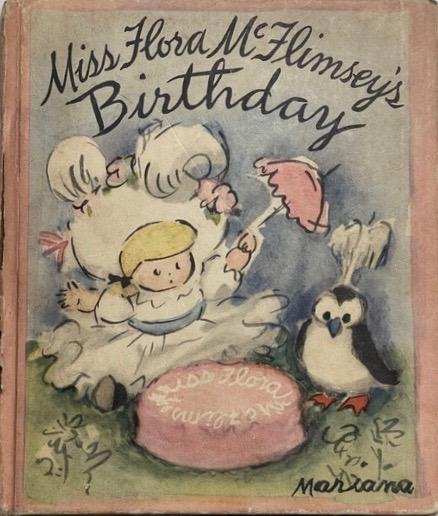

Curtiss’s best-known children’s book series featured a doll named Flora McFlimsey, written under the single pen name Mariana (her paternal grandmother’s first name). One reviewer called Flora McFlimsey the modern successor to Raggedy Ann, while another said it was the sweetest book character she had ever met. Curtiss described Flora McFlimsey as a cross between Queen Victoria and Mae West.

Her children’s books, published between 1945 and 1988, aimed to instill a sense of wonder in children, something she felt was diminishing in modern society.

She illustrated her books with watercolors, using dolls from her own collection as models, and also illustrated several books for other authors. Curtiss enjoyed collage art, incorporating silk, lace, feathers, and glitter into her watercolor paintings of antique dolls.

In a 1951 East Hampton Star article, Mrs. Robert Cheney, an East Hampton librarian, said her favorite Mariana book was “Doki,” about a Native American baby. “It was so popular that the well-worn book had to be rebound,” she said.

In 1962, Curtiss traveled to the Hotchkiss Elementary School library in New Castle, Del., for its dedication in her name. In 1966, the American Institute of Graphic Arts selected her book “The Journey of Bangwell Putt” for its annual list of 50 books of excellence. Today, her books are rare and hard to find, and they can be pricey, some as high as $250.

Fascinated by old toys and dolls, Curtiss not only wrote about them but also amassed an extensive collection. She participated in several exhibitions at Guild Hall in the 1950s and 1960s, displaying antique dolls and toys. In the 1970s, she visited the John M. Marshall Elementary School and Most Holy Trinity School to speak about her books.

Little is written of Curtiss’s personal life, so I turned to genealogical records. She was born in Ohio in 1890 and raised in Atlanta. The middle of three children, she had an older brother, Blair, and a younger sister, Elizabeth. Her father, Frank Osborne Foster, was a successful regional sales manager for the S.S. White Dental Manufacturing Company, working in Ohio, Philadelphia, London, and Atlanta. After retiring, he served on the Atlanta City Council and was a founding member of the Atlanta Rotary. Curtiss’s brother, Blair Foster (1888-1979), became a prominent attorney in Atlanta.

As a young girl, Curtiss quit her piano lessons, and her mother insisted she pick up something else. She chose art. She studied at Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans, the Art Students League in New York, and the Grande Chaumiére art school in Paris. While she was studying abroad in 1910, her mother, Mary Blair Foster, died of heart failure. Curtiss was just 19. Her father remarried the following year.

In 1920, Curtiss married Harold Stockly Curtiss at age 29; he was 41. A New York City automobile shop manager, he had been drafted in 1918 into the New York National Guard 7th Infantry, the 107th Regiment, known for the heavy casualties it took in France during World War I. They married two weeks before his official release from service. The following year, her 26-year-old sister, Elizabeth, died of tuberculosis. Within six years, her husband, Harold, passed away in New York City. She had lost a husband and a sister in a short period of time. Neither Curtiss nor her siblings had children.

During the Great Depression, Curtiss was employed by the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal initiative under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As part of the National Arts Index project, she was drawing and painting antique toys and dolls in museums. She credited this job with igniting her lifelong career as a children’s book writer and illustrator.

“It was here that I discovered another world — the world of pre-mass production days, of beauty and fine craftsmanship,” she said. This was where she first encountered the Flora McFlimsey doll, originally created in 1864 and inspired by a popular 1857 poem by William Allen Butler, “Nothing to Wear,” which her mother used to quote.

Curtiss passed away at Southampton Hospital in 1978 at the age of 88. Before her death, she donated her papers to the de Grummond Children’s Literature Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi. A collection of watercolors can be found at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. A school librarian who wrote Curtiss a fan letter shortly before her death unexpectedly received a parcel containing Curtiss’s Flora McFlimsey doll and others. The dolls sold at auction in 2012 for $3,500.

One never knows what they will learn taking a drive to the dump!

Hilary Osborn Malecki, a local history researcher, was born, raised, and still lives in East Hampton.