The late John Gosman Sr., a jazz aficionado, could not have known what was to come when he asked the saxophonist Lee Konitz, in 1972, to assemble a group to perform at Gosman’s Dock in Montauk. “I gave him $300 and put him up for the night, fed him and the band,” Gosman, who died in 2021, told this reporter in 2018.

It was the first of what has become a more than half-century tradition, free Sunday concerts that have brought legends including Toots Thielemans, Ruth Brown, Dick Hyman, Fathead Newman, Joe Farrell, the Heath Brothers, and Billy Hart to Montauk Harbor.

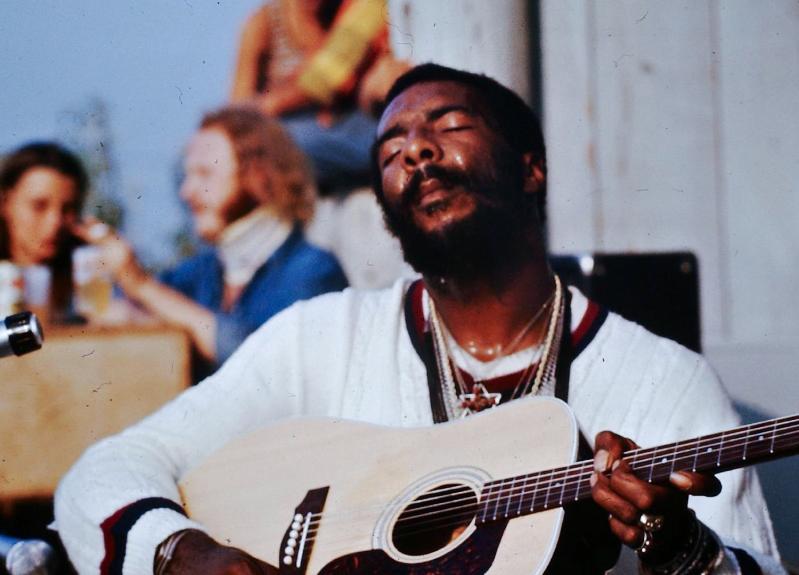

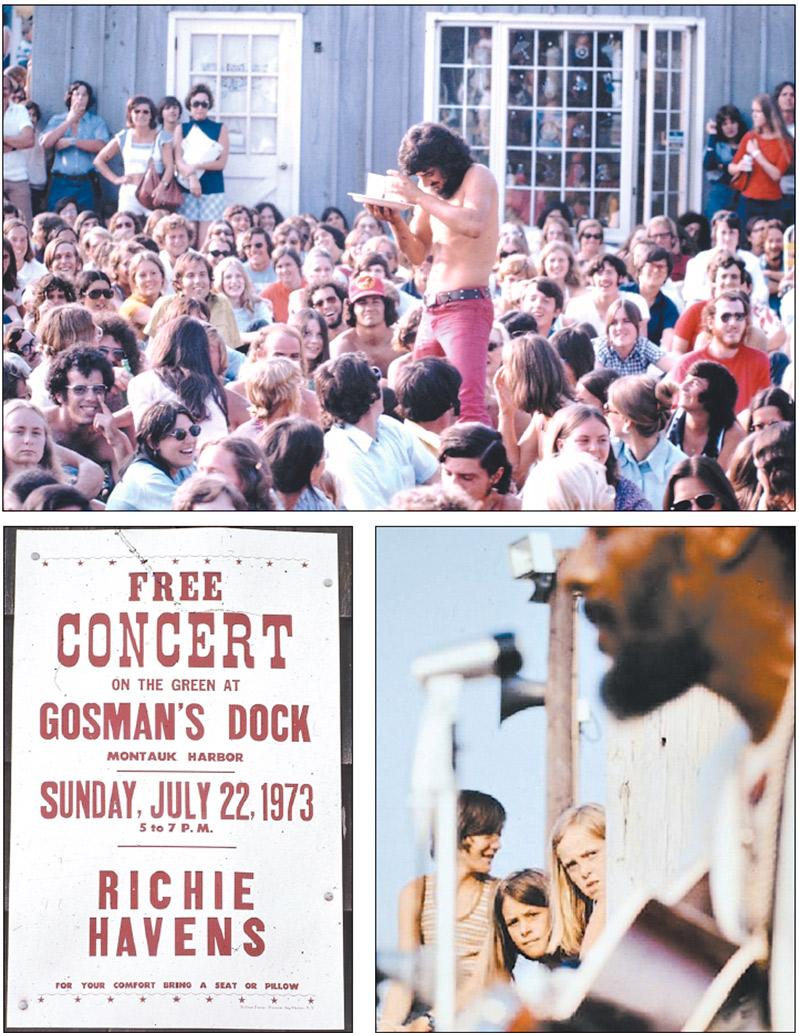

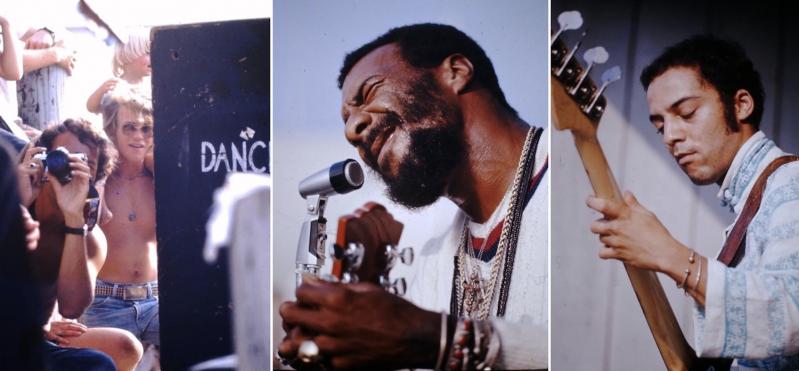

But one concert stands out from the innumerable performances on the outdoor stage at Gosman’s. Saturday will mark the 50th anniversary of a performance by Richie Havens, one that none who were there are likely to forget.

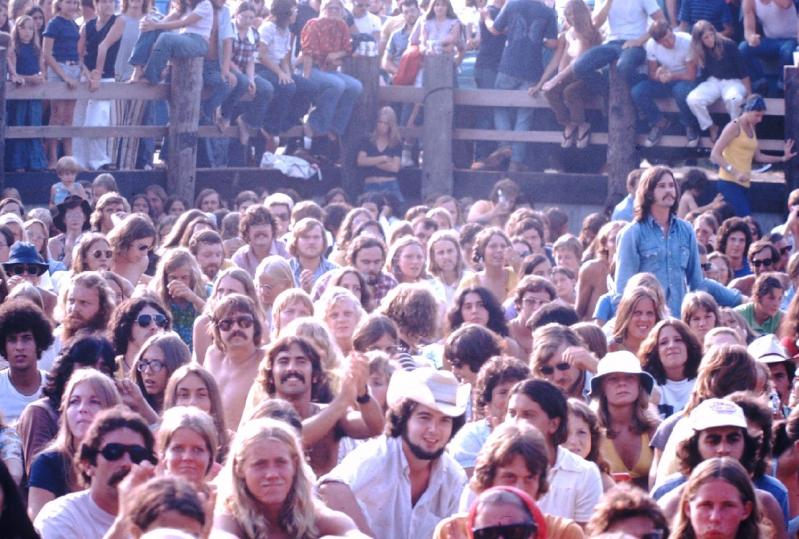

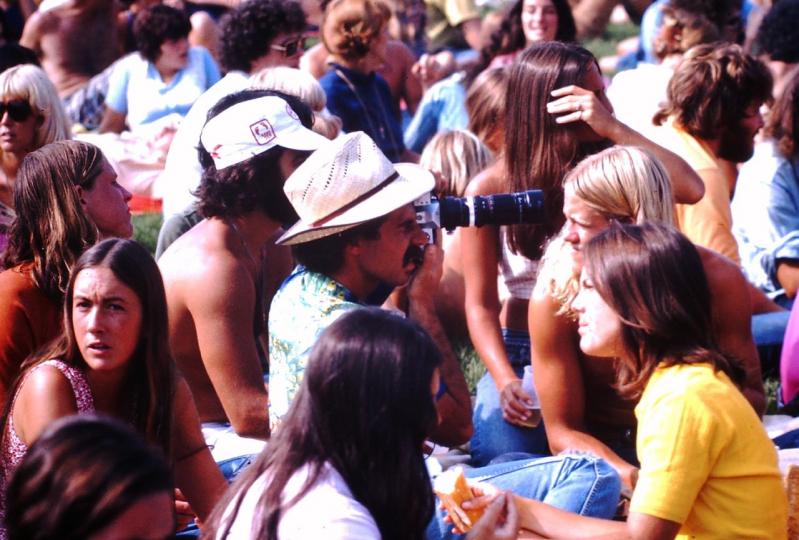

Ask any of the thousands in attendance, and they will likely remark on the sheer number of people there. The crowd, in fact, is all that a 6-year-old would-be reporter clearly remembers.

It was not quite four years after Havens, who died in 2013, had memorably opened the Woodstock Music and Art Fair. With the scheduled opening artist stuck in traffic, Havens, whose popularity had grown since arriving on the Greenwich Village folk-music scene in 1961, reluctantly agreed to open the four-day festival.

“Richie was always willing,” said Walter Parks, who played guitar with Havens from 2001 until Havens’s retirement a decade later. “He was a can-do guy. If a promoter asked him to perform first, he might privately be not so crazy about it, but in order to be a servant to the bigger cause, Richie would say yes.”

With sparse accompaniment — his own bassist was unable to reach the site, with some 300,000 people descending on a farm in rural Bethel, N.Y. — Havens was electrifying, stirring the sea of humanity before him. He closed his set with a spellbinding improvisation incorporating the spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” It came to be known as “Freedom,” an anthem memorably featured in the film “Woodstock.”

It was “one of the most significant moments in American musical history,” said Peter Honerkamp, an owner of the Stephen Talkhouse in Amagansett, where Havens performed annually for more than 20 years, “for being the opening act, for what the concert became, and for the fact that his performance was so powerful. The magnetism that he brought to that performance really became symbolic, in many ways, of that whole time, and certainly of that concert.”

“Richie Havens wasn’t scheduled to be the opening act of the Woodstock Festival,” according to the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts, “but, in retrospect, it is hard to imagine anyone else doing it.”

“We have something very much in common in that we first learned of him when we were very young,” Mr. Parks told this reporter. “I learned of him when I saw ‘Woodstock.’ When I heard him play, I thought, this is all the world’s music in one man.”

The first jazz concert a success, Gosman, with the help of Pat DeRosa of Montauk, a saxophonist who died in March at age 101, booked a supergroup comprising Thad Jones, Mel Lewis, Pepper Adams, George Mraz, and Roland Hanna. “A real bunch of all-stars,” Gosman remembered. “From that point on, we used to do them every other week,” starting on the first weekend after the Fourth of July.

He had met Havens in the bar at Gosman’s Restaurant, where celebrities regularly partied in the 1970s. “I said, ‘Would you consider doing a concert for us? I can give you $500.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, I can do it.’ “

July 22, 1973, would see the fourth concert at Gosman’s, and “audiences were getting bigger with each one,” said Brian McKernan, who was working at Gosman’s Clam Bar at the time. A stage had just been built — previous performances had taken place on a patio — and an adjacent parking lot turned into a “village green” complete with a gazebo. “There was much more room for the audience now,” he said, “which was fortunate, because Havens attracted a massive crowd.”

But Montauk’s answer to Woodstock nearly didn’t occur at all. As it happened, Havens was to play a July 21 concert in his native Bedford-Stuyvesant, in Brooklyn, with a rain date of the 22nd. The concert was rained out, and Havens was obliged to perform in Brooklyn that day. “He called me the day of the concert,” Gosman remembered, “and said, ‘Sorry, I can’t do it.’ By that time, I had put a little ad in The Star.”

By 10 a.m. “the place was full,” he said. “When he called and said, ‘I can’t make it,’ I said, ‘You’ve got to come, we’ve got thousands of kids here now. They’ll wreck the place.’ By that time, the pall of marijuana outside, you could take a deep breath and get stoned.”

But Havens “was always punctual,” Mr. Parks said. “Richie really believed in the common man, and he would give his time generously to just anybody.” He, “like any of us, enjoyed the attention, but he also gave back so much.”

Havens was flown to Montauk, Mr. McKernan said, “and apparently someone had told him that Gosman’s is right next to the airport,” when in fact they are across the harbor from each other.

A borrowed rowboat solved that problem, “but then Havens somehow dropped his dentures, which slid under the boat’s floorboards,” Mr. McKernan continued. “An anxious few minutes passed as Havens was rowed across Montauk Harbor while feeling about beneath his seat for his teeth, without which he wouldn’t have been able to sing.”

“Fortunately, he found them and then gave a two-hour concert every bit as powerful as the one at Max Yasgur’s dairy farm four years earlier.”

By showtime — 5 p.m. — “there must have been 5,000 kids there,” Gosman said. Parked cars snaked on either side of Flamingo Road all the way to North Farragut Road, a mile and a half away, he said.

“The green and adjacent areas were packed,” Mr. McKernan remembered, “and so many hippies had climbed atop Gosman’s Fish House there was genuine concern that the roof would collapse.”

“I was on my boyfriend’s shoulders watching the concert,” DeRosa’s daughter, Patricia DeRosa, recalled. “It was packed, people were coming out on the train. It was the greatest concert ever.”

Jane Bimson, a sales representative for The Star, also recalled the crowds during furtive breaks at Gosman’s Restaurant, where she worked as a waitress.

Such was the crowd size that it, too, was reminiscent of the Woodstock festival, Mr. McKernan said. “I wish I had been able to watch more than just a few minutes of the concert, or even taken a few photos, but I was too busy with my co-workers serving the madhouse crowds.” Thirty minutes in, “we stopped selling food and concentrated on meeting the seemingly endless demand for soda and beer.” They poured from multiple taps for more than two hours, “grateful that we had an ample supply of beer kegs and syrup canisters,” he said. “We were rolling in refills about every 15 minutes.”

Cleanup after the concert took quite a while, he said, “but the elation everyone felt at Havens’s fantastic performance lasted far longer.”

The crowd was so thick that Havens could not leave, Gosman said, “so we took him by boat over to the airport, paid for his plane fare, and they flew him to Flushing Airport. It was really a hectic day.”

“The Richie Havens concert held at Gosman’s Dock last Sunday was a huge success,” The Star reported four days later. “Record crowds turned out for this second of a series of free concerts.”

“He was a great performer, a lot of passion in his songs,” Gosman remembered. “A very modest guy, too.”

“He was the sweetest guy in the world,” Mr. Honerkamp agreed. “Gentle, soft-spoken, easy to deal with, affable. He liked everyone” at the Talkhouse.

Mr. Parks remembered his audition with Havens, in a Jersey City basement studio, as demonstrative of the man. “We only played one song,” he said. “The same intensity he played ‘Freedom’ at in the movie of Woodstock, he played in that basement for me. It showed me that this man respects me enough to be completely, 100-percent present in the moment. Also, that was the way I would come to learn from Richie that he could do anything.”

“When he tended to the song at hand and the person he was talking to, even a stranger, he passed love around the world,” Mr. Parks said. “It will live way beyond Richie Havens’s lifetime.”