After a dead humpback whale was found floating six miles off Montauk on July 24, scientists from the Atlantic Marine Conservation Society are seeking to pinpoint the cause of death.

“It’s pretty inconclusive what we’ve found so far,” said Robert DiGiovanni, the founder and chief scientist of the conservation society, which conducted a necropsy of the animal on Friday on a cordoned-off portion of Montauk’s Umbrella Beach. “The whale was severely decomposed so we didn’t really find a lot of internal organs,” said Mr. DiGiovanni.

The whale was female, just over 30 feet in length, and the carcass had bite marks, said Rachel Bosworth, a spokeswoman for the organization. “It is difficult to determine when the animal died or its age due to decomposition and predation,” she said.

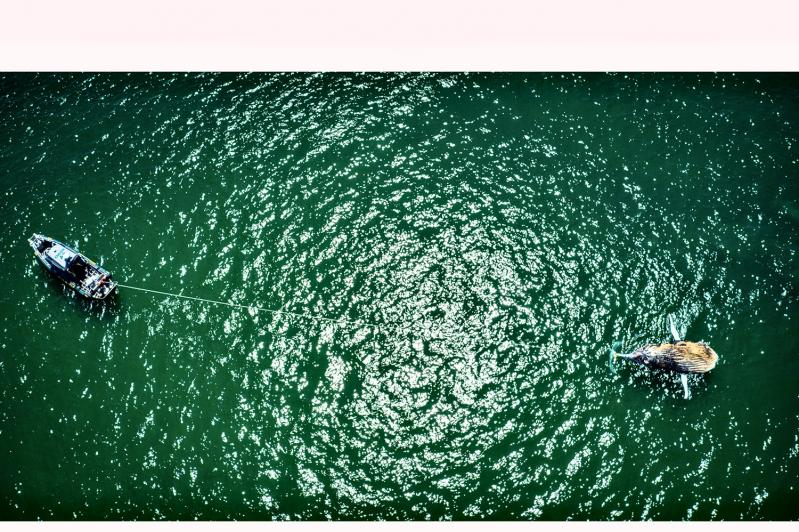

The whale was first discovered by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and reported to the marine conservation society. By Friday, as the whale was drifting closer to shore, members of the East Hampton Town Marine Patrol and the D.E.C. towed the whale onto the beach.

“It took over an hour to go a mile and a half,” said Joe Vish, a harbormaster, “because we didn’t want to pull the tail off.” Mr. Vish said a boat with a crew from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries had also been on hand. The group had been hoping to tag great white sharks that might be feeding on the dead whale, he said, but none were found.

After the whale was placed on the beach, the carcass was examined by Mr. DiGiovanni and his colleagues, Kimberly Durham and Jennifer Lopez.

“We take tissue samples, and get in the abdomen, and look at the skull and see if there are any broken bones,” said Mr. DiGiovanni. “You look at each organ system and see does it look normal or abnormal?”

Upon initial examination, he said, he did not see signs that the whale had been entangled in a fishing net. (On July 15, a humpback whale had gotten trapped in a gillnet off of Town Line Road in Sagaponack and had ultimately freed itself.)

The A.M.C.S. scientists were able to recover the contents of the whale’s stomach on Friday and will analyze them to determine what species it was feeding on, said Mr. DiGiovanni.

“This is the time of year when the whales would be here putting on weight, so we’ll examine how well it was feeding, and if there’s a problem,” he said.

The samples collected will be sent to a pathologist, said Ms. Bosworth, and it may take several months before a more detailed analysis is available.

As the necropsy was proceeding on Friday, with scientists slicing the carcass into smaller chunks, a backhoe and dump truck were positioned nearby, waiting to cart the remains away.

“All the cuts we make make it easier for us to get into the area we want to examine, and they also make it easier to move the animal,” said Mr. DiGiovanni, who added that he still finds it hard to work on the dead creatures.

“Even though this was scientific and we were able to collect information, what we like to see is free-swimming healthy animals,” he said.

Getting the answers to what led to this particular death, he said, can help many other whales.

“This is now 32 large whales that have come up in two and a half years,” he said. “We’re seeing more animals, but we might be seeing them because they’re more plentiful. That’s what we want to understand.”

The state’s stranding hotline, which should be used to report both living and deceased whales, dolphins, seals, and sea turtles, is 631-369-9829. Alerts of sightings ºcan be sent to [email protected].