In any inventory of the most influential documentary filmmakers, certain names inevitably appear: Dziga Vertov, Robert Flaherty, Marcel Ophuls, Frederick Wiseman, Michael Apted, Errol Morris, Albert and David Maysles, and the Maysles’ contemporary and onetime associate, D.A. Pennebaker.

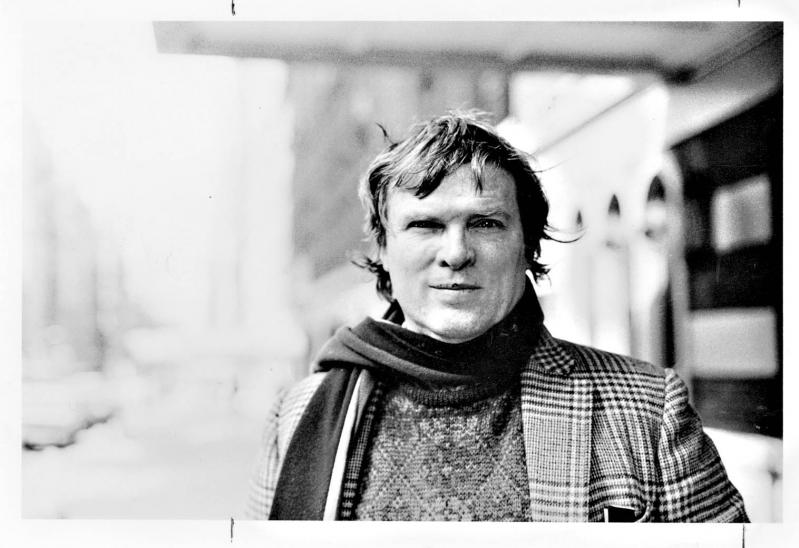

Mr. Pennebaker, who, along with Ricky Leacock, Robert Drew, and the Maysles brothers, is widely acknowledged as one of the progenitors of cinéma vérité, or direct cinema, died last Thursday at home in Sag Harbor. He was 94.

Asked by Daniel Eagan during a 2017 interview for Film Comment magazine to describe his visual style, Mr. Pennebaker explained, “You just watch. . . . Don’t interpret, don’t explain. I kind of got that idea from Flaherty. . . . The thing I understood about this kind of filming . . . is that you have to begin from the beginning. Like any story. You can’t get somebody to tell you what happened and have it work.” In order to “just watch,” he needed a camera that didn’t yet exist, one that synchronized sound and image. Along with Drew and a friend with a machine shop, he developed the synchronous-sound camera, which eliminated the need for voiceover narration. The camera was first used for the 1960 film “Primary,” which Drew directed and Leacock, Albert Maysles, and Mr. Pennebaker photographed. The film focused on John F. Kennedy as he traveled the country in his campaign against Hubert Humphrey for that year’s Democratic presidential nomination.

Mr. Pennebaker left Drew Associates in 1963 to form a partnership with Leacock, and in 1965 he covered Bob Dylan’s concert tour in England. The result was “Don’t Look Back,” a landmark that has since been selected by the Library of Congress for the National Film Registry. When asked by Mr. Eagan if Mr. Dylan was aware of his presence during the filming, Mr. Pennebaker said, “Always, always, always was, but he didn’t care. It was a homemade camera. . . . There were no lights, no equipment at all except the camera. And that’s all he would ever see. Sometimes I didn’t even have a sound person.”

Another landmark in his career was “The War Room,” which he made with Chris Hegedus, who began co-directing with him in the mid-70s. They were married in 1982. The film followed Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, but focused less on Mr. Clinton than on his campaign manager, James Carville, and his communications director, George Stephanopoulos.

Of that film, Mr. Pennebaker said, “I don’t think it’s possible to make a film about a person running for president. You can follow him, you can be with him a lot, but basically what you’re doing is a home movie, while he’s got the six o’clock news to worry about. . . . No matter how much money is involved, you’re not going to get anything that’s worth anything.” He and Ms. Hegedus were nominated for a best documentary feature Oscar for the film. Mr. Pennebaker received an Honorary Academy Award in 2013. Among his other notable films are “Monterey Pop,” the film of the 1967 rock concert that included the Who, Janis Joplin, and, most memorably, Jimi Hendrix, who followed his performance by setting his guitar on fire. The New York Times critic Renata Adler said of that film, “It is possible that the way to a new kind of musical . . . may begin with just this kind of musical performance documentary.”

Another landmark is “Town Bloody Hall,” his film of a 1971 panel discussion at Town Hall in New York City that pitted Norman Mailer against the writer Germaine Greer (“The Female Eunuch”), the journalist Jill Johnston, the literary critic Diana Trilling, and Jacqueline Ceballos, the president of the New York chapter of the National Organization for Women.

Jacqui Lofaro, the executive director of Hamptons Doc Fest, said, “The documentary world without D.A. Pennebaker is an American landscape without its iconic redwoods. Penny pushed limits to capture human nature, never judging or manipulating. His cinéma vérité style placed viewers in the moment, watching life unfold. Losing Penny leaves us without our North Star.”

Susan Froemke, a Springs filmmaker who was a longtime collaborator with the Maysles brothers, said, “You can’t overestimate the impact Pennebaker had on the development of documentary filmmaking in the U.S. Smart, charming, and kind, Penny’s ability to establish a deep trust with his subjects allowed his stories to unfold naturally before the camera without a preconceived script or narration.”

According to Don Lenzer, a director and cinematographer who lives in Amagansett, “Penny was an inspiration to all of us, but particularly to those of us who were part of the generation that just succeeded him. He ignited us with his unflagging confidence that nonfiction film could be every bit as dramatic and entertaining as theatrical fiction film.”

Donn Alan Pennebaker was born on July 15, 1925, in Evanston, Ill., to John Paul Pennebaker and the former Lucille Levick. After serving in the Navy and studying engineering at M.I.T. and Yale, he worked with his friend Francis Thompson on “N.Y., N.Y.,” an impressionist short film. “Francis . . . taught me what an artist was,” he said. “He understood that you committed to something for life.”

Mr. Pennebaker went on to make “Daybreak Express,” a film of a five-minute ride on the Third Avenue El set to music by Duke Ellington, and then joined Drew at Time-Life before setting out on his own.

In addition to Ms. Hegedus, he is survived by his son Frazer, who has produced many of his father’s documentaries; seven other children, Stacy, Linley, Jojo, Chelsea, Zoe, Kit, and Jane Pennebaker; 13 grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.