After 80 Years Montaukett Papers Return, Sort Of

One day in about 1885, George Fowler put pen to paper and signed away his remaining rights to his ancestral land at Montauk.

Mr. Fowler, a member of the Montaukett tribe, was among a shrinking number of native people who remained then, some two and a half centuries after the arrival of European colonists, and their diseases and economic exclusion.

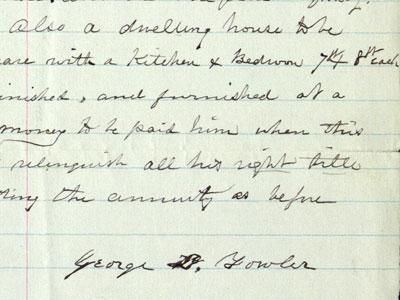

In the quitclaim agreement he signed that day, Fowler gave up all of his right, title, and interest to what had been his home in exchange for an annual payment from Arthur W. Benson, the founder of the Brooklyn Gas Company and developer of Bensonhurt who had just a short time earlier become the owner of all of Montauk’s approximately 11,500 acres.

The Fowler agreement is part of a cache of documents preserved at the Brooklyn Historical Society and now available digitally from the East Hampton Library that had been fought over for much of the 20th century. Interest in the material has increased following an agreement that will preserve Mr. Fowler’s house in the Freetown section of East Hampton, which Mr. Benson had given him in exchange for his property at Montauk.

The Benson papers, as they have come to be known, contain a significant trove of records, including account books of the Proprietors of Montauk going back to the early-19th century and a 1724 record of a land sale between the Montauketts and the East Hampton Town Trustees. Those involving Benson’s takeover of the land paint a picture of his efforts to consolidate his newly bought property and rid himself of earlier promises made to the Montauketts.

“The ready availability of the information provided in these scans is almost the stuff that dreams are made of from a research standpoint,” said Gina Piastuck, who runs the library’s Long Island Collection.

Unlike the rest of East Hampton, Montauk was carved off early on by the town trustees and left in the hands of a group of private citizens. A court upheld the Montauk Proprietors’ title to the land in 1851, and in its decision, ordered that all of the records relating to Montauk be taken from the town and given to the proprietors.

By 1879, the Proprietors had decided to sell out, and Mr. Benson was the winning bidder, offering $151,000. However, before the deal was finalized, the Proprietors, on advice of their lawyer, decided to turn all of the material over to the town. This did not sit well with Mr. Benson, who about a year later managed to convince them to instead give them to him. In a journal entry among those digitized by the East Hampton Library, Mr. Benson was quoted as promising to keep the papers “in a safe at Montauk and make available for viewing to East Hampton and Southampton residents.”

The importance of the papers became clear early on when members of the Montaukett tribe sued Mr. Benson, then his estate, claiming that their rights had been obtained by fraud and “undue influence by the Bensons and their agents and employees.” Instead of being made available to the townspeople, John A. Strong, an authority on the Montauketts, wrote in a 1993 book on the tribe’s losses, the documents were kept by Mr. Benson and used by his lawyers to plan legal strategy.

Interest in the papers continued into the 20th century. In 1922, The East Hampton Star reported that they had been given by Mr. Benson’s granddaughters to the Long Island Historical Society. In 1934 the East Hampton Town supervisor appointed local justices of the peace, Merton Edwards and William T. Vaughn, to a committee to investigate if copies at least could be obtained.

Negotiations with the Brooklyn Historical Society, as the organization was by then named, continued through the 1930s to no avail. In 1935 The Star reported that the records contained “accounts and receipts of the Proprietors of Montauk, a large number of documents relating to keeping cattle there, and 17 of the original Indian deeds and agreements. A number of these Indian deeds have never been transcribed and so are not to be found in the printed records of the town.”

A delegation from the library that included the late president of its board, Tom Twomey, and Ann Chapman and Janet Ross, visited the Brooklyn Historical Society in 1997 without success.

Finally in 2013, Mr. Twomey and Dennis Fabiszak, the library director, were able convince the society to loan the papers for digitization on the Long Island Collection’s state-of-the-art system with the help of Norbert Weissberg, a library donor and Brooklyn Historical Society trustee.

The society’s then-director personally delivered the three boxes containing the Benson papers, and during about a month’s work they were carefully opened and scanned. Steve Boerner, a library archivist, spent long hours cataloging the material and studying its chronology.

Tantalizing to all involved, a last box of documents awaits in off-site storage in Connecticut. Mr. Fabiszak said that he hoped that material could be added, though it could be a while.

Copies of the Benson papers are available on the library’s website under Long Island History.