Back in Fashion & Better than Ever

Look at photographs and paintings of early 20th-century gardens on the East End and what do you see: roses, first and foremost. Climbing roses, frothy with blooms overflowing pergolas, arbors, walls, and fences. At the very pinnacle of high fashion were beds filled with the new, repeat flowering China and tea roses, surrounded by low clipped hedges of boxwood.

Surprise of surprises, ornamental grasses crop up, used in a variety of ways.

Most gardens in East Hampton’s summer colony had trophy double borders filled with nicely staked flowers, very much influenced by Gertrude Jekyll, and some sort of formal water feature. What the images don’t show are the legions of gardeners required to keep these spun sugar fantasies picture perfect.

One hundred and more years later, most East End gardens have to make do with fewer gardeners. Times have changed in other ways as well. Gardens and plants are as subject to trends as clothing, but when an old style is rediscovered and popularized decades later it returns with a contemporary twist.

Water features have evolved into swimming pools and naturalistic ponds. Instead of labor-intensive double borders, today’s more natural flower gardens tend to have a core of ornamental grasses and shrubs with sturdy perennials that no longer require staking and deadheading and that flower over long periods.

The rose probably remains the most beloved of all flowers. Where they used to flower once and briefly, and were followed by black spot, beetles, mites, and aphids, today’s roses can flower from spring through frost with foliage as fresh in October as it was in April with little to no maintenance, except to clip fragrant blooms for the house.

Garden fashion over the last 25 or 35 years has been motivated as much by environmental awareness and sustainability as the need for lower maintenance, however you interpret that, and the appeal of the prairie aesthetic as a refuge from urban and suburban daily life.

That grasses were popular in the Victorian period is difficult to fathom. My memory doesn’t go back quite that far, but I do dimly recollect the last vestiges of a Victorian bedding-out scheme, backed by pampas grass and probably cannas, at the Elizabeth Park Rose Garden in my hometown of Hartford.

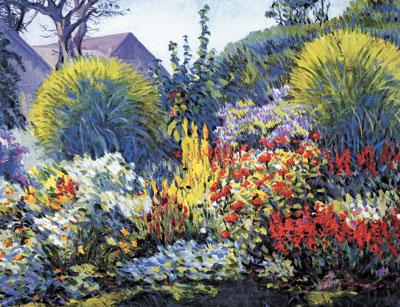

Beginning in the mid-19th century in England as well as the United States, the Victorians and Edwardians used a fairly broad range of hardy ornamental grasses. A photograph of a Southampton garden shows a small formal pool surrounded by fountain grass; a similar pool at the Wiborg estate in East Hampton seems ringed by rushes or reeds. Perhaps even more surprising is a 1927 oil of a summer flower garden incorporating two large clumps of Miscanthus sinensis, what the Victorians called Eulalia grass.

Some contemporary designers advocate landscapes that look untouched by human hands, using grasses without cultivar names. Go out to Napeague Meadow Road in Amagansett in late summer to see in its perfection what they try to emulate. In gardens, the result is often masses of floppy, bent plants, not at all what nature had in mind.

Here is where I get on my bandwagon to put in a good word for cultivars. The word cultivar is a contraction of “cultivated variety.” They are developed by sowing seeds of, say, native switchgrass, observing the seedlings and plants as they mature, and separating out those with interesting characteristics for further observation.

Seedlings from the same source can mature to different heights, with different flowers and flowering times, different autumn coloring, and different structure. (Think children from the same parents.) Nurserymen select ones with different ornamental traits and give them cultivar names so designers and gardeners know exactly what to expect when they use them.

Unfortunately, this is where some people have difficulty. I’m often told, “I don’t want a plant with a name, I want the real plant.”

In a redo some years back, switchgrass was planted at the sides of the steps half-way down the Mimi Meehan Native Plant Garden behind Clinton Academy in East Hampton Village. By late August the grasses would flop so badly we had to cut them back. They were replaced with two different cultivars: Northwind, very upright and tall, and Haense Herms, a shorter variety that turns brilliant red in autumn. This year they were cut down at the end of February only because we had to protect the new growth as the plants broke dormancy. The grasses with their floating seed heads had turned a lovely buff color but were otherwise in prime condition.

Variety in roses, on the other hand, comes from deliberate breeding. Over the centuries man has had a love-hate relationship with the queen of flowers. Roses have almost always been popular, and there have been wave after wave of different types coming into fashion as we persisted in trying to improve the race. Until the 20th century most roses flowered for a few weeks and afterward looked anemic or used up a lot of space with their long, rangy canes. No wonder roses were segregated in areas away from houses.

Repeat blooming hybrid teas, and their even more floriferous cousins the floribundas, were introduced by the hundreds, if not thousands, during the first half of the last century. People complained that breeders removed the fragrance from these stylish modern roses, and, unfortunately, the plants required rigorous spraying and fertilizing to maintain their looks and health.

Beginning in about the 1970s, perhaps because of the influence of Rachel Carson and the emerging environmental movement or perhaps because the pace of modern life picked up and people spent less time at home, interest in roses began to wane, even in England.

During the early days of my gardening life, like many new gardeners, I was totally seduced by roses: modern roses, heritage roses, David Austin roses. I tried them all, and each had its own disappointment. As the years went by it seemed always either to rain or threaten rain before I got to the maintenance, so it became haphazard. The roses went into decline, and, then, did I actually give thanks when the deer showed up and put an end to them?

In the last decade it appears that we are coming close to attaining the holy grail of roses, at least in our area, thanks in large part to Kordes, hybridizers from northern Germany, and Peter Kukielski, the curator of roses at the New York Botanical Garden. When Mr. Kukielski began a brave experiment there, he replaced most of the bushes in the rose garden in a search for longer blooming varieties with improved disease resistance. Each year the performance of the plants is evaluated and rated. (You can look at the garden’s Web site for lists of roses and their performance.)

I’ve toured the garden on a number of occasions. It is clear the best plants there are bred mostly by Kordes. Germany passed a law 25 years ago that banned treating roses with chemicals so Kordes had a head start breeding roses that would perform well and be beautiful without them.

Honestly, I don’t own shares in the company, but Kordes roses are some of the toughest you’ll ever find. They are bred specifically to be grown without chemicals or growth enhancers. Many of their newer plants have good fragrance and elegant old-fashioned looks as well. That’s what we’ve been looking for in roses for hundreds of years.

Among them are the Kordes lines called Fairy Tale roses, Vigorosa roses, and Climbing Max roses. Last year I ordered Kordes roses for the East Hampton Garden Club plant sale from Palatine Roses in Ontario, which introduces many of its new roses in North America. They arrived as dormant, bare-root bushes on April 1, were distributed Memorial Day weekend as vigorous, good-size plants, and by summer were busy putting out armloads of gorgeous blossoms.

As these roses from Kordes and (I hope) other breeders gain more exposure and become better known, I suspect roses will once again come back into the vanguard of fashion and popularity.