Donald XLV, Richard II: Mirror Images?

A ruler with authoritarian tendencies. Inside, endless palace intrigue as warring factions vie for influence. Outside, bullying of allies and threatening of adversaries. A tight-lipped investigator seemingly closing in and soon, perhaps, to compel a climactic showdown.

Is this the White House, or a work of Shakespeare?

And if the latter, is it comedy or tragedy? “That’s what I don’t know yet,” said Richard Horwich, of Northwest Woods in East Hampton. “We’re only in, I would say, Act Two.”

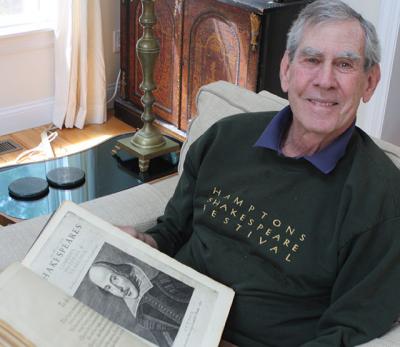

Mr. Horwich, a retired professor who taught at New York University and Brooklyn College, leads the Shakespeare Discussion Group at the Amagansett Library and serves as dramaturge, or adviser, with the Hamptons Shakespeare Festival. He is also the author of “Shakespeare’s Dilemmas” (“the scholarship is thorough and admirable,” William M. Peterson wrote in The Star’s review).

Likening President Trump to a Shakespearian character is not new. In a 2016 article in The Los Angeles Times, written before the election, Charles McNulty asked, “What would Shakespeare, the greatest detective of the soul of man in literary history, have made of Donald Trump?” After turning to the comedies for material, he settled on “Julius Caesar” and “Coriolanus,” citing their “almost prophetic reading of our current moment.” Last year, New York’s Public Theater was harshly criticized for a depiction of the assassination of a very Trumpian Roman ruler in its production of “Julius Caesar.” One performance was disrupted by protesters.

“Tyrant: Shakespeare on Trump,” a recent book by the scholar Stephen Greenblatt, defines a tyrant, Mr. Horwich said, as “a leader manifestly unsuited to govern, someone dangerously impulsive or viciously conniving or indifferent to the truth” — someone who, Mr. Greenblatt writes, has “limitless self-regard, the law-breaking, the pleasure in inflicting pain, the compulsive desire to dominate. He is pathologically narcissistic and supremely arrogant. He masquerades as a populist but has only disdain for the common people.”

Does this remind you of anyone?

Mr. Greenblatt, Mr. Horwich said, cites characters and works including Jack Cade in “Henry VI, Part 3,” Richard III, Macbeth, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Cori olanus,” and Leontes from “The Winter’s Tale.” “He makes a very good case for most of them,” he said, “but I don’t see Julius Caesar, Lear, or Coriolanus as tyrannical. But then, I don’t yet see Trump as a tyrant — only a wannabe, who might develop into one under the right circumstances, unless someone like Richmond, Macduff, or Brutus stops him.”

Rather, Mr. Horwich sees Richard II as the closest analogue to the 45th president of the United States, despite some obvious differences. “What so many people despise about Trump is that he’s trampling on American institutions, breaking our national taboos, dragging our world reputation down, compromising our integrity. That’s exactly what did Richard in. He’s in the same business as Trump: real estate.”

“Richard, like Trump, kept alienating his supporters until there were none left, a process we’re watching unfold. Richard, like Trump, was a military hawk, so intent on defeating and annexing Ireland that he bankrupted the treasury to fight a war there.”

“And in his sexual proclivities,” Mr. Horwich said, Richard II “is the mirror image of Trump. Trump is so blatantly sexist and macho, so eager to prove his manhood by grabbing [women], bragging about the size of his ‘fingers,’ etc., that he’s a laughingstock. Richard isn’t quite that, but characters in the play are always making snide, veiled references to his effeteness, even effeminacy — and in fact, in real life, he designed his own clothes and is credited with the invention of the handkerchief. That’s distinctly un-Trumpian, yet there’s a kind of . . . I’m not going to call it sexual dysfunction, but a kind of a removal from the mainstream, one to one side, the other to the other, that makes him unpopular and the subject of ridicule.”

There are, of course, outcomes apart from comedy and tragedy, “and one of them is irony,” Mr. Horwich said. “Shakespeare’s tragedies, as they get later and later, the endings become more and more ironic. It becomes more about the failure of kings, in particular, to realize dreams or hopes or ambitions, and fail their countries. Lear is an example of that.”

What follows Act Two in, perhaps, “The Tragicomedy of Trump,” is anyone’s guess. “Who knows how all this is going to play out?” Mr. Horwich asked. “He might be deposed, he might have his throne usurped. . . . Will the Republicans somehow get their way and defang” Robert Mueller, the special counsel, “and derail his investigation? I would bring it all into line with the fates of various and sundry of Shakespeare’s kings.”

The Shakespeare Discussion Group will meet on June 9 at 10:30 a.m. at the Amagansett Library.