‘Galloping Grandfather’ Hailed

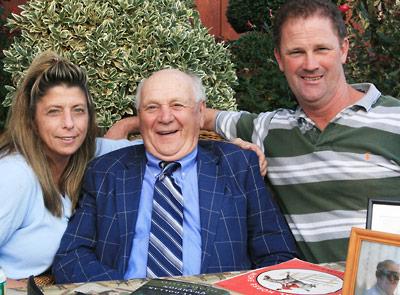

Harry de Leyer, “the Galloping Grandfather” who is now a great-grandfather as well, spent four hours here at East End Stables Saturday afternoon signing copies of Elizabeth Letts’s best seller about him and his Cinderella show-jumper, Snowman, an event that enabled many of his former students to reconnect with their teacher, who has lived in Dyke, Va., for a number of years.

The story of Snowman, a former plow horse de Leyer rescued from the glue factory in 1956, and with whom he went on to win national show-jumping championships, is one of sport’s most compelling. The long gray gelding for whom the sky seemed to be the limit when scaling fences was show-jumping’s equivalent to Seabiscuit.

Ms. Letts, who lives in Baltimore, was there that day too, and said she got the idea for “The Eighty-Dollar Champion: Snowman, the Horse That Inspired a Nation” when, quite by accident, she saw on the Internet a black-and-white photograph of Snowman jumping over another of de Leyer’s horses, Lady Gray.

She wrote de Leyer a letter, she said, and so began a collaboration that resulted in a very well-written book, published by Ballantine Books, that debuted at around the time of the Hampton Classic at number 10 on The New York Times best-seller list for hardcover nonfiction.

Suzanne Wolfson, who had interviewed the 84-year-old de Leyer on radio station WBAZ the day before, said she remembered having been fascinated by Snowman and de Leyer’s story when she read the children’s book about them in the 1960s. Later, she rode at East End Stables, which is owned by Andre de Leyer, one of Harry’s sons, and his wife, Christine.

Andre and his sister Harriet de Leyer, who in the book is credited with giving Snowman his name, taught her, said Ms. Wolfson, who still rides there. As for the interviewee, she said, “He was so much fun.”

In a long line of people waiting for their books to be signed, Carol Kurzig, a former student of de Leyer’s, recalled that while she’d started riding late, “he made me jump in my first lesson.”

Mark Goldstein said that de Leyer had “taught me and my whole family. . . . He sold me a horse named Twiggy and told me not to interfere when we approached a four-and-a-half-foot wall. He said the horse would jump it, and he did! Harry gave us a lot of confidence . . . and he made it fun. He enriched all of our lives.”

During his first lesson at East End, de Leyer asked Jerry Schwabe, if he’d ever jumped a fence. Schwabe had ridden at the Claremont stables in New York City, but had only jumped cross rail fences that he said, bending close to the ground, were “this high.”

“The ones he had me jump the first day were much higher,” Schwabe said. “He’d be running and waving his hat to get the horse to go over.”

He and his wife subsequently bought horses. “We’d go in the evenings,” he said wistfully, looking away from the barn over the fields, “down there, bareback, no reins, no nothing. . . . I have good feelings about Harry.”

Asked what it was like to jump, Barbara Sansone, Schwabe’s wife, said, “It’s like flying in heaven.”

“I didn’t know if he was alive,” Letts said, when asked to continue the story of how she’d come to meet de Leyer, who is to present trophies and ribbons at the Washington International Horse Show at end of this month. “He called me . . . it was in 2008 . . . He really helped me set the story within its historical context. In 1956 I wasn’t born yet! Snowman was more of a story of my parents’ generation.”

Given the success of her book, and should a film of “The Eight-Dollar Champion” be made, it will also become a story of this one.