In the Name of Unity

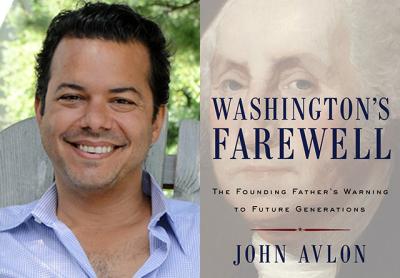

“Washington’s Farewell”

John Avlon

Simon & Schuster, $27

“You campaign in poetry. You govern in prose,” Mario Cuomo once famously quipped. But in rare moments of American history, our leaders have provided us with words more akin to Scripture, inspired texts that have outlined the nation’s principles, affirmed its commitments, and articulated its deepest purpose.

George Washington’s Farewell Address, the subject of John Avlon’s absorbing new book, stands as one of those texts, a foundational document of our political system and “the most famous American speech you’ve never read.” In “Washington’s Farewell: The Founding Father’s Warning to Future Generations,” Mr. Avlon, editor in chief of The Daily Beast, hopes to rescue Washington’s last words as president from their recent obscurity so that an American nation now riven by excessive partisanship and existential anxiety might rediscover its wisdom.

Mr. Avlon’s book could hardly have come at a more opportune time. After the ugliness of the 2016 campaign and the unsettling first weeks of the Trump Administration, Washington’s Farewell Address seems the prescription especially needed for the ills that plague our nation. Yet as unremembered as Washington’s last words now are for most Americans, for more than 100 years after its publication in 1796 the Farewell Address stood as the most revered and trusted document in the nation. Schoolchildren memorized passages, ministers incorporated it into their sermons, and presidents regarded it as the touchstone for all their decisions in office. Little did any of these people know that Washington had been working on his address for five years or that others had helped him draft it.

Washington hadn’t wanted to be president, desiring instead a quiet life at his beloved Mount Vernon after his time leading the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. But he accepted the call of duty to the nation’s highest office with reluctance. He was right to be reluctant. As adored as he had been as general, Washington as president faced vicious critics, a deadlocked Congress, and an unruly cabinet that splintered into warring factions. Bitter divisions between North and South and urban and rural regions grew heated.

“By the end of his first term, Washington had enough,” Mr. Avlon writes. He secretly asked James Madison to begin work on a valedictory address to mark the end of his presidency. But persuaded that the country would fall into civil war if he didn’t stay in office, Washington accepted a second term as president. The Farewell Address would have to wait.

In his second term, Washington passed the drafting work from Madison to Alexander Hamilton. John Jay, governor of New York, also had a hand in writing the Farewell Address. In the final weeks before publication, Washington furiously finalized the text, paring down Hamilton’s flowery language for his own plain style that, as he described, the “yeomanry of the country” would understand.

The Farewell Address, 6,088 words spread across 54 paragraphs, appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser on Sept. 19, 1796, and was republished in newspapers across the country in the months following. The address shocked its readers, serving as it did to announce Washington’s retirement from public life.

That announcement provided the address’s most immediate effect, establishing the precedent of the peaceful transfer of power and creating the tradition of a two-term limit to the presidency. (The 22nd Amendment, ratified in 1951, would turn tradition into law after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four-term presidency.)

But what of the address itself and the guiding principles it set forth? Mr. Avlon outlines the document’s six “pillars of liberty”: national unity, political moderation, fiscal discipline, virtue and religion, education, and foreign policy. Each grew out of the political circumstances of Washington’s presidency, lessons the president had learned and warnings for the future. Mr. Avlon presents the stories behind each pillar, what he calls an “autobiography of ideas.”

Washington’s plea for national unity reflected his concern with the growing factionalism in Philadelphia, evidenced by the emergence of political parties and the nation’s worsening regional divisions. But it also owed to his knowledge of the history of ancient republics that had fallen apart. Like many of his contemporaries, Washington owned a copy of Edward Gibbon’s “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” and read it as a dire warning for his own young nation. In his Farewell Address, Washington stressed that the independence and liberty Americans so cherished was dependent on their unity and would be threatened by any acts of division. Tellingly, the two words Washington used most in his address were “citizen” and “Union,” appearing eight and 20 times in the text, respectively. Washington was writing the unifying power of a national identity into the American consciousness through his Farewell Address.

For Washington, the call to national unity also depended on political moderation. While Washington lamented the rise of political parties, what he really feared was the extremism and hyper-partisanship those parties could unleash, thus destabilizing the republic. In advocating national unity based on a shared sense of citizenship, Washington believed the temptation to political extremism could be constrained, tempered further by a devotion to reason over emotion.

On foreign policy, the Farewell Address’s most cited maxim forbidding “entangling alliances” actually never appears in the document. Those were Thomas Jefferson’s words in his first inaugural address. The Farewell Address, instead, advocated neutrality. Mr. Avlon stresses that Washington meant this as a policy of independence rather than isolation, a view shaped by the bitter fights between Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans and their support for England and France, respectively. Washington believed 20 years of neutrality would allow the United States to become powerful enough that its independence would be secure. But he did not intend the U.S. would never act on the global stage.

Still, the isolationist interpretation of Washington’s words prevailed until the 20th century. In the closing section of his book, Mr. Avlon demonstrates how succeeding presidents drew on the Farewell Address to understand and articulate their leadership. Like other influential documents, including the Bible and the Constitution, the Farewell Address was no instruction manual, but instead a statement of principles that were always subject to interpretation.

Leaders picked and chose from the document, lifting out passages that they believed spoke to — and justified — their approach to the issues of their day. On the brink of civil war, Abraham Lincoln called on the Farewell Address’s appeal to national unity. Woodrow Wilson twisted the logic of Washington’s foreign policy prescription to propose nation-building and the creation of the League of Nations. Dwight D. Eisenhower copied the Farewell Address’s warning to future generations in his own farewell that cautioned an overgrown military-industrial complex threatened democracy.

What might President Trump make of Washington’s Farewell Address? Mr. Avlon’s book provides no thoughts, as it was likely completed before the election in November. Certainly, the history that Mr. Avlon provides shows that nearly all presidents have looked to the Farewell Address for wisdom and guidance. Yet whether or not Mr. Trump ever turns to Washington’s words, Mr. Avlon compellingly argues that the Farewell Address — printed in full in the book’s appendix — is not a document only for presidents but rather for all Americans to read and know, “providing a useful lens for assessing our own decisions as we face the future.”

Neil J. Young is the author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.” He lives in East Hampton.

John Avlon lives part time in Sag Harbor.