New Effort to Ban Three Chemicals Used on Long Island

With three million Long Islanders dependent on a single underground aquifer for drinking water, and the annual use of millions of pounds of pesticides, fungicides, and herbicides, local environmental groups have asked the State Department of Environmental Conservation to immediately ban the three most frequently found chemicals, atrazine, metalaxyl, and imidacloprid, from use on the Island.

In a January press release from the Citizens Campaign for the Environment, one of the organizations that has called for the ban, these chemicals are said to have been linked to cancer and kidney and liver damage, in addition to having negative effects on the environment and shellfish populations. The National Resources Defense Council recommends that consumers use certified filters to remove volatile organic compounds from their water until the chemicals are phased out.

Other groups that have asked for the ban include the Long Island Sierra Club, the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, the Sustainability Institute at Molloy College, and the Group for the East End.

For over 50 years, farmers internationally have used the herbicide atrazine to fight weeds in corn and other crops. The European Union banned it in 2003, citing “ubiquitous and unpreventable groundwater contamination,” following bans in France, Denmark, Germany, Norway, and Sweden. The same year, however, the Environmental Protection Agency approved its continued use in the United States. Nine years later, atrazine is still a widely used herbicide, with more than 60 million pounds applied annually across the country.

Atrazine’s effects have been documented extensively. One source, pubmed.org, cites evidence that atrazine interferes with reproduction and development, and may cause cancer, with amphibians, mammals, and humans affected even at low levels of exposure. Another concern is the chemical’s potential to act synergistically with other contaminants.

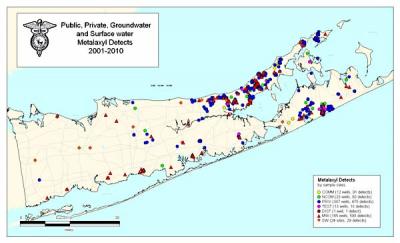

The D.E.C.’s own Long Island Pesticide Use Management Plan, issued in December, shows that imidacloprid was detected 782 times at 182 locations on Long Island, metalaxyl 1,292 times at 727 locations, and atrazine 126 times at 88 locations. Suffolk County, with the largest agricultural sales in New York, and in particular the East End, are of greatest concern.

In addition, the D.E.C.’s Web site notes that many other chemicals in use on Long Island have been detected at concentrations in excess of New York State standards. Once in an aquifer, they remain there for decades or longer, discharging contaminants into surrounding surface water resources, including freshwater and tidal wetlands, the Web site states.

According to Dick Amper, executive director of the Long Island Pine Barrens Society, a new water quality assurance entity is necessary to assure that water quality standards are met. In his opinion, because there is no single identity charged with protecting groundwater, it is not being adequately protected. The Suffolk Health Department regulates drinking water while the D.E.C. regulates surface water.

Mr. Amper called on others to take action, including manufacturers, distributors, and users, health advocacy groups, homeowner and civic associations, farmers, vineyards, nurseries, golf courses, and public health and town planning organizations.

“This is the biggest environmental challenge that has ever confronted Long Island,” Mr. Amper said, emphasizing that homeowners must be a part of a “shared commitment and sacrifice to turn this around, before the next generation of children cannot drink the water anymore.”

Residents can do their part by maintaining cesspools adequately, returning unused pharmaceuticals to appropriate facilities, paying attention to chemicals in personal care products and solvents used in the home, and avoiding chemical fertilizers, he said.

The D.E.C. has also recommended citizen attention to household chemicals, asking the public to avoid “weed and feed” combination products. It has reported that 62 of the contaminants found in groundwater are contained in personal care products, including anti-bacterial soaps and toothpastes.

Paul Wagner, vice president of Treewise Ecological Landscape Management in East Hampton, said that the insecticide imidacloprid is widely used in lawn care here for grub control. His company is among those that use natural or biological methods to promote healthy soil. He also said hydrogen peroxide, which breaks down readily, was a safe fungicide.

Commenting on the massive effort he thought it would take to really protect groundwater, Mr. Amper said the amount of nitrogen from sewage had increased in the upper glacial aquifer by 40 percent since the last study 17 years ago and deeper levels have increased by 200 percent. “It is really bad,” he said. “If the present trend continues, water will be undrinkable before 2050. It is a disaster in the making, and it raises the hair on the back of my neck.”