It was about a dozen years ago, but Lee Bieler remembers well the telephone call he got from his friend Tim Van Patten. A television and film director, Van Patten is one of HBO’s go-to lensmen for many of its most prestigious productions: The Sopranos, Masters of the Air, Game of Thrones. Van Patten wanted to discuss a project HBO was gearing up to do with a potential showrunner whom he thought Bieler might know.

“I hadn’t seen him for a while, but one day my phone rings and he says, ‘Hey, I have a question,’ ” the 73-year-old Bieler recalled in a voice feathered with warmth and respect for the subject. “He says, ‘Do you know a guy named Allan Weisbecker?’ He goes, ‘What is his backstory? What is his deal?’ ”

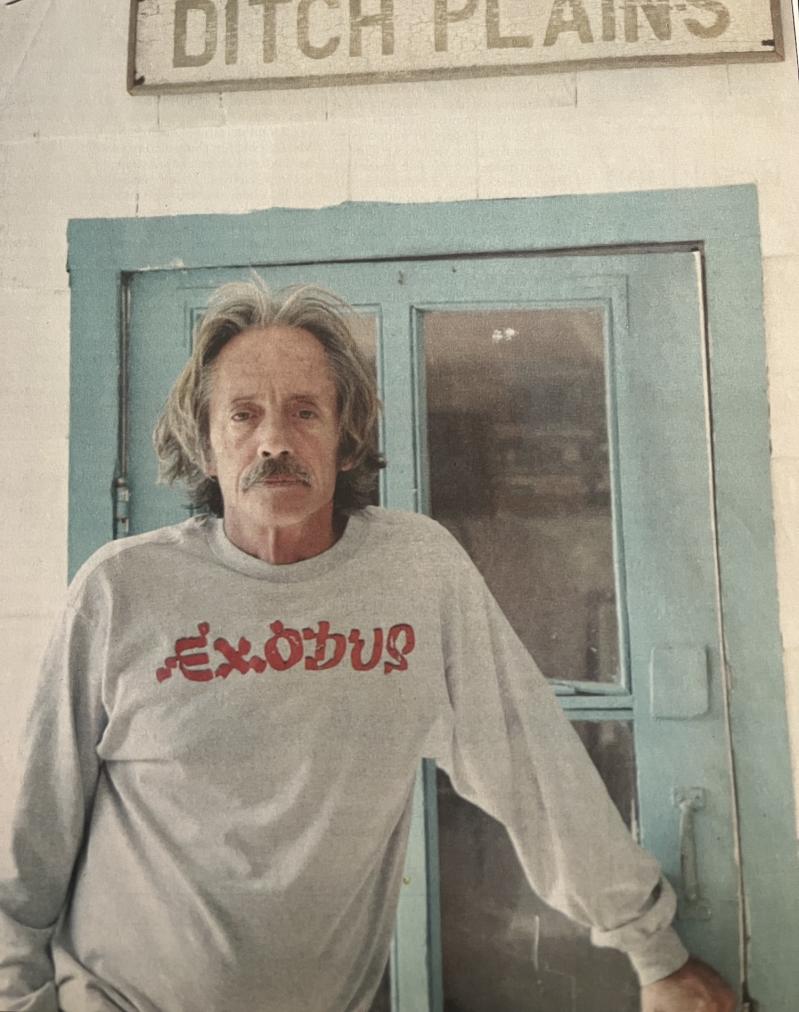

It’s a question perhaps best answered by a biographer in 750 pages, a psychiatrist af- ter years of sessions, or anyone following a map of the wandering Weisbecker’s travels. The biographical facts of the late 75-year-old Weisbecker’s life are easy enough to assemble. Single words convey his professions and preoccupations: Surfer. Gonzo writer. Moviemaker. Drug smuggler. Photojournalist. Adventurer. Conspiracy theorist.

His list of credits is similarly illuminating: the surfing novel Cosmic Banditos. The autobiographical In Search of Captain Zero and Can’t You Get Along With Anyone? A Writer’s Memoir and Tale of a Lost Surfer’s Paradise. The TV shows Miami Vice and Crime Story. The magazines American Photo, Men’s Journal, Popular Photography, Sailing, Smithsonian, Surfer, Surfing, and The Surfer’s Journal, for which Weisbecker wrote or took photographs. Sean Penn, John Cusack, and Brad Pitt have all bought or pursued options to produce films of Captain Zero and Cosmic Banditos, but none has been produced yet.

“Weisbecker was some kind of modern-day Jim Morrison — alone with everybody, cruising and writing, dreaming and surfing,” Surfer Today wrote cogently of Weisbecker’s passing in October. Bieler, who relishes telling the stories of his friend, has his own favorite word for him.

“Let’s just say that Allan was a pirate,” Bieler said. “He had a lot of life experiences that he pulled into his writing. The surfing world. The pot world.”

Montauk to the World

Weisbecker’s writings of the surfing world put him on par with world-class fin-free surfer Derek Hine. Hunter S. Thompson was probably a vast influence on Weisbecker’s work, said one of his best friends, 73-year-old Tony Caramanico of Montauk.

Weisbecker was a tall, rather gangly teen when the two met on a Montauk beach in the early 1970s. They bonded over surfing Long Island shores, and Caramanico, an artist and local businessman, probably stayed in touch with Weisbecker as much as anyone did during the latter’s peripatetic life. Weisbecker’s was an important voice for the surfing world for its combination of his skill as a surfer and writer, Caramanico said.

“Cosmic Banditos came first, but Captain Zero was Allan at his best,” Caramanico said. “Allan wasn’t a pro surfer or anything like that, but he was very good. He was an accomplished surfer, and he lived that lifestyle. He was always trying to go surfing. The thought of surfing was always there, right around the corner.”

Never a best seller, Captain Zero superficially resembles two works of another seminal surfing chronicler, John Milius, who co-wrote the script for Apocalypse Now and co-wrote and directed the surfing paean Big Wednesday. Weisbecker’s nonfiction narrative combines his love and pursuit of surf with his journey from Montauk across the U.S. to California and then south in search of a childhood friend, Christopher, who had disappeared in Central America on a surfing jaunt five years before.

His only clue to Christopher’s whereabouts is a postcard signed “Captain Zero.” Like Willard’s in Apocalypse, Weisbecker’s journey mixes his narrative ruminations on Christopher, the goal of his search, with sharply etched descriptions of the people and situations he encounters along the way. Publishers Weekly called the book “a lovely personal reflection that mixes the right amount of dreamy meditation with page-turning allure.”

“Weisbecker clearly delights in storytelling as much as he enjoys language itself. . . . Such imagery with a balance of pathos and humor make Weisbecker’s account very worthwhile reading.”

The book is like a surfer’s version of another epic tale of a compulsive on- ward journey, Kerouac’s On the Road, and has built a worldwide cult following among surfers, Caramanico said.

Captain Zero serves another important function, said Biddle Duke, an East Hampton writer, publisher, and ardent surfer. “It’s very much the story of surfing here in the ’70s and ’80s,” said Duke, east’s founding editor. “That was the scene: drugs, travel, adventure, doing anything to figure out how to keep surfing and see the world with a surf board. Long Island was behind California and Florida for sure,” as a surfing locale, Duke said, “which was part of the thrill of being part of it in the ’60s and ’70s. It was emerging and being discovered. Breaks were being discovered and surf shops were opening here for the first time.”

The original surfers of the region — Bieler, Russell Drumm, Caramanico, and Weisbecker — were among the many who pioneered surfing as a commercial recreation and avocation for the Island. Their discovery of the Island’s rocky coves and curved beaches, which are necessary for creating the long-breaking waves that surfers cherish, was a major contribution to Montauk culture, Duke said.

“There are waves even on the Great Lakes. Each coastal region has its own surf scene,” Caramanico said. “California has better waves because they don’t have a continental shelf. We have better waves than the Gulf Coast because we have the Atlantic Ocean and the rocky coves in Montauk.”

Riding the Nose

Montauk was critical to Weisbecker’s life. As he relates in Captain Zero, he had lived in New York City when his father took him to “the end-of-the-road place called Montauk.” The place “had a frontier feel. To a 9-year-old boy with an active imagination and whose adventuring had been limited to the writings of Jack London and Robert Louis Stevenson, Montauk’s towering, saw-toothed crags, desolate rock-strewn shores and densely impenetrable woods seemed preternaturally wild and remote, and untamed territory where fearsome beasts surely lurked.”

Fatefully, his father took him to sea the day after they arrived in Montauk on an expedition of snorkeling and spearfishing, which Weisbecker had learned the previous winter at a Y.M.C.A. pool. Weisbecker’s ripe description makes plain that this was the moment that transformed him from a mere combina- tion of his parents’ traits — his mother’s courtly warmth and cheerfulness; his father’s moody-dark hermitage — into the solitary adrenaline-fueled wanderer and diarist he became.

“Picture how the boy’s hands are shaking as the tools of the coming sea hunt are unpacked, his father smiling in anticipation of the kill, of blood in the water. Imagine the shivering in the boy’s gut as his fear of night monsters is overwhelmingly supplanted by the utterly human fear of a very real unknown. . . . Now picture him an hour or so later, standing on this same promontory, seawater-wet and breathless from the climb back up the cliff, diving knife strapped to his waist, and, dangling from a stringer, a small blackfish slain by his own hand. Imagine him gazing at that now-familiar blue vastness and wanting to be out there again, right away.”

“Knowing all that has happened since, it’s clear to me that my life would have turned out very differently had I not conquered my fear and entered the water that day,” he wrote.

Years later, when Weisbecker joined the Long Island surfing scene in the 1960s, his timing was prescient. The Montauk beaches were beginning their ascent to one of the East Coast’s premier surfing destinations. And he himself was a pretty good surfer, though not professional-grade. The mid-1960s were a time when great surfers rode the nose on longboards, heavier surf boards difficult to control. Weisbecker learned quickly to ride the nose. Most surfers who try it never get that good, Caramanico said.

“It is difficult,” said Caramanico. “Everybody buys these longnose boards — they call them nose riders. Basically, they’re wide-nose, flat boards, and a lot of people that buy these particular style boards, they don’t even wax the nose because they don’t go near it. Basically, they’re riding the wrong-size board for their capabilities, but people don’t know that.”

When Kyle Paseka of East Hampton met Weisbecker on Long Island in the 2000s, he was already good friends with her late husband, Rusty Drumm. She could see why he was never without someone lovely on his arm. Tall and ruggedly handsome, Weisbecker could have a sharp tongue — woe betide his opponents in arguments.

“He could piss people off,” she said. “He wasn’t a sellout and he was very, very smart. He would always be the smartest guy in the room.”

But he had a gallantry about him as well, Paseka said. “I’ll always remember we were at a party and he was sitting at my table. He was very suave and debonair,” she recalled. “I said something like, my champagne’s warm, and he grabbed my glass and just tossed the contents over his shoulder and said, ‘Well, then, let’s get you some cold champagne.’ And it just was such a great gesture. You know what I mean? It was funny the way he just tossed it right out. And it was at a fancy wedding. He just flung it over his shoulder . . . I’ll always remember him doing that.”

After Montauk, Weisbecker was a student at the University of Hawaii during the early 1970s, when that scene exploded with some of the greatest surfers of the day, Caramanico said.

The F-ing Boat

Weisbecker had a good pirate’s knack for putting himself next to the treasures of his day and a good writer’s ability to turn his adventures into stories. Best of all for him, he avoided the scourges of his time.

Chiefly, he never went to Vietnam, instead leaving Hawaii and Montauk and spending time in France, North Africa, Central America, and other places in search of waves and, as he himself frankly disclosed, dealing drugs.

He smuggled hashish from North Africa and marijuana from Colombia into the U.S. It is in describing this period of his life, the 1970s and ’80s, that Caramanico and Bieler’s voices become more circumspect.

“He never did cocaine. Don’t ever put that in there. That wasn’t heroin,” Caramanico said of Weisbecker’s dealings.

Weisbecker’s account, again in Captain Zero, has him successfully smuggling his biggest marijuana haul, 20,000 pounds, out of La Peninsula de la Guajira, Colombia — “the Wild West epicenter of the mammoth Colombian marijuana trade” of the mid to late 1970s. Nicknamed at first just “the Boat,” the 80-foot craft he and Christopher and two hired-on crewmen used was a sunken “Down Island former banana hauler of questionable provenance (and no legal residence),” rescued from 40 fathoms off Montauk Light. So little of the boat’s equipment worked that they wondered if the craft was cursed. It was so mechanically woeful that they inserted an F-bomb amid the name they gave it: the F-ing Boat.

Thanks to his drug-dealing, this period was a time of economic prosperity for Weisbecker and by the early 1980s he had used it to propel himself into scriptwriting gigs with Miami Vice and another TV show directed by Michael Mann, Crime Story. He bought a house in Montauk and seemed content. He had also begun writing scripts for Hollywood that kept him in cash the rest of his life. One of his scripts got made: Beer, a 1985 comedy that satirically examines an advertising firm’s woeful attempts to keep a dying American brewery afloat. With each renewal of the options of those deals, Weisbecker got fresh financial infusions to propel his lifestyle.

Yet his drug exploits, detailed in mostly humorous tones in Cosmic Banditos, had become something regrettable to him by the time Captain Zero was published in 2001. He describes in Zero how he had a Spanish copy of the former available in the mobile home where he spent the last few decades of his life, but declined to get it when a Mexican fisherman asked after the book.

“I don’t want to show it to him,” Weisbecker wrote in Zero, “because the story is about a high-living, nihilistic marijuana smuggler, and even though that part of my life is long gone and over with I’m embarrassed about it here and now, sitting with a man of his simple tastes, who works so hard for very little.”

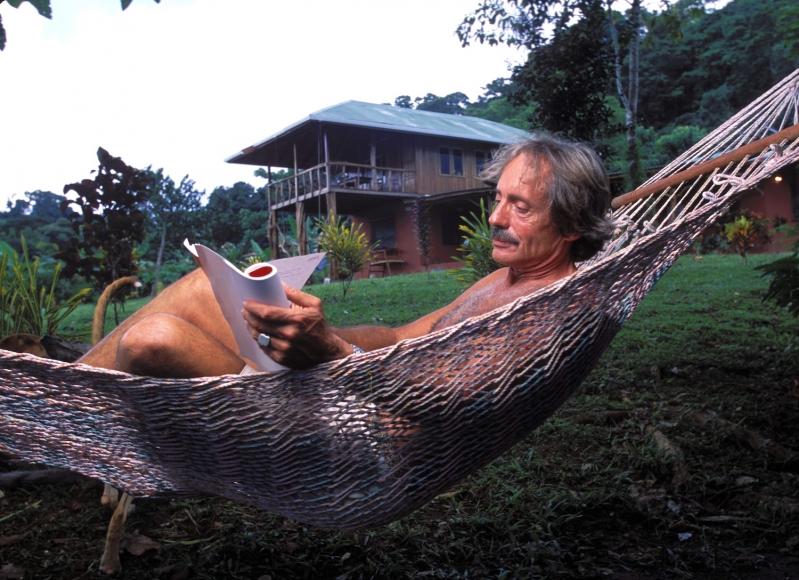

A Big Camper

Weisbecker’s end is a difficult subject for his Long Island friends. They saw very little of him into the early 2000s and less as that decade passed into history. A difficult time in Costa Rica, where illnesses and a bad relationship with a girlfriend — Weisbecker never married — soured the man’s ebullience. It was as if the bright cheerfulness of Weisbecker’s mother had in the writer’s mind been swamped by the dark reclusiveness of his father. Caramanico never met Allan C. Weisbecker Sr., but his son told Caramanico of a visit to his father in upstate New York that ended abruptly because the elder Weisbecker never came to the door.

“It’s kind of tragic, because he became his own worst enemy in a sense that he self-destructed,” Caramanico said. “Maybe his emotions, certain things that were happening to him, he couldn’t deal with. . . . He became even more closed in and the hermit part of him came out. Even though he was outgoing, inside he was starting to tear himself up.”

“I think at that point he got a little lost,” Caramanico said. “Then he abandoned us. He got that big camper” — a 2008 Four Winds Chevrolet R.V., covered with a galleryful of bright images of horses, beaches, and sunsets — “and moved out of Montauk.”

Caramanico speaks of the abandonment with no bitterness, but sadness. When Weisbecker died, he was in Michigan, away from the Long Island coast that helped shape the best parts of him, and his friends don’t speak of the details of his death. Paseka said Weisbecker had become a full-blown conspiracy theorist with a blog he wrote late in his life. Its patrons speculate that he was murdered, but she doesn’t seem to believe it. Maybe it is not that surprising that rumors of grandiose murder plots would circle around the death of a man who lived life outside the boundaries, on a grand scale.

Part of the reason for his Long Island friends’ reticence might be that they haven’t yet really had a chance to mourn him. A memorial service of some sort is planned for Weisbecker this fall. Perhaps a more complete reckoning with his passage will come with that.

But one also senses within his friends an acceptance of Weisbecker’s untimely death. The bravery and beauty of the man was his willingness to face his own restless darkness amid his globe-trotting adventures. Paseka recalls him describing his troubles with a surfer’s term for the terrifying and sometimes deadly moment that surfers face on the shore- ward side of a huge wave just before it slams down on them.

“I remember once sitting on a bench with him and we were watching the waves and he said, ‘Oh, I got caught inside,’ ” Paseka recalled.

“ ‘Caught inside?’ ”

“Yeah. It happens in life, too,” Weisbecker said. “Sometimes you get caught inside.”