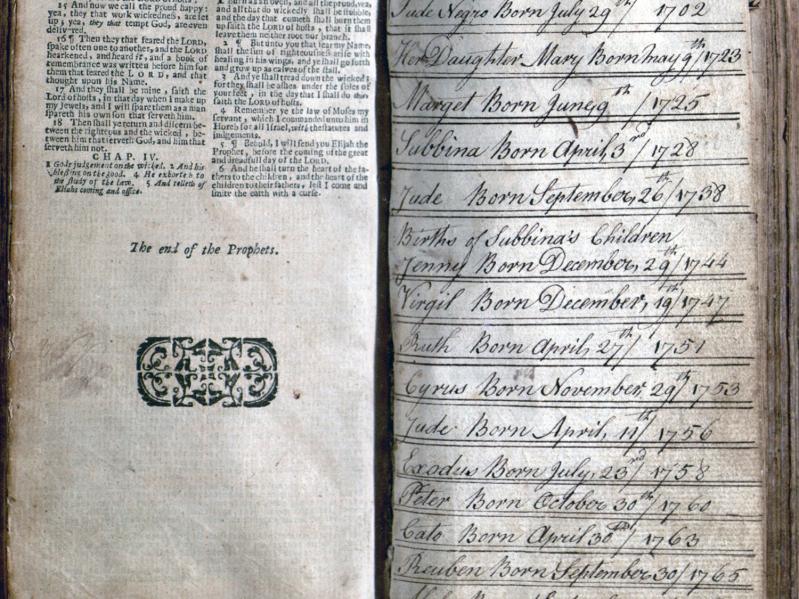

On July 29, 1702, a woman named Jude was born. It is uncertain who came before her, but the birth, death, and marriage dates of her descendants are documented in a family Bible that had been passed down for more than a century. After years of safekeeping by the family, the Crook Family Bible was donated to Bridgehampton’s Hampton Library sometime after 1923.

Although families have documented their histories in Bibles since the 15th century, this family Bible is unique. It belonged to Cato Crook (1763-1841), a formerly enslaved man who lived in Bridgehampton. Cato had been enslaved by Herrick Rogers (1775-1827) and Micaiah Herrick (d. 1840) but was freed in 1817. He was literate, as evidenced by a letter he wrote in 1819 to Elias Smith (1772-1839) of Smithtown regarding his niece, who had escaped Smith’s “hard usage.” With little information about him, this letter and the Crook Family Bible help us paint a broader picture of Cato’s life.

Cato’s documentation has enabled us to identify several enslaved individuals and their family network. Using research done by the Plain Sight Project, we can parse that certain individuals listed in the Crook Family Bible were enslaved by David Gardiner (1738-1774), Abraham Gardiner (1720-1782), and Lyman Beecher (1775-1863). Cato’s decision to document his family history allows a better understanding of enslavement on Long Island and the experience of African-Americans on the Island before the 20th century.

The digitization of the Crook Family Bible is part of an ongoing project between the Long Island Collection and the Hampton Library’s Elise Quimby Local History Room, designed to increase access to historical materials pertaining to Long Island. Most important, partnerships like this one allow us to make materials like the Crook Family Bible accessible, highlighting otherwise hidden histories of eastern Long Island.

—

Megan Bardis is a librarian and archivist in the East Hampton Library’s Long Island Collection.