Vija Celmins is a visual seductress. From her early treatment of everyday objects to the water and sky images that have become her trademark, she has fashioned an art that skirts the line between representation and abstraction in a way that is mesmerizing.

Leaving viewers to wonder what they are looking at and experiencing, the long-time Sag Harbor resident does what she can to have them look, and then come back to look again. This is immediately apparent in her two-floor retrospective at the Met Breuer in New York City, “Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory,” which opened last month.

As a young artist in the 1960s, she, like many of her generation, was reacting to and retreating from those still mired in the tenets of the New York School. It likely helped that she attended the University of California at Los Angeles for an M.F.A. beginning in 1962 and remained in that city for two decades.

Rather than adopting grand, gestural, and abstract action painting, or what she termed in a catalog essay “painting about itself,” she turned to what might be termed realistic banality, “looking at simple objects and painting them straight.” Her contemporaries, often under the designation of Pop Art, were exploring similar terrain, but with winking irony and humor. She wasn’t looking for a commercial gleam or colorful “BLAM!” Her aim was, and still is, authenticity.

The exhibition encompasses 120 objects from more than five decades. The fifth floor of the Met show highlights these early years and includes her early 1960s studio object paintings as well as mid-to-late-1960s paintings she made from “found images” in magazines, books, and her own photographs. Then as now, she considers the appropriation of images for her work as “re-describing” rather than copying. Through this process she is “remaking the image, leaving my traces, bringing it into another space or context,” as she said in an interview quoted in the catalog.

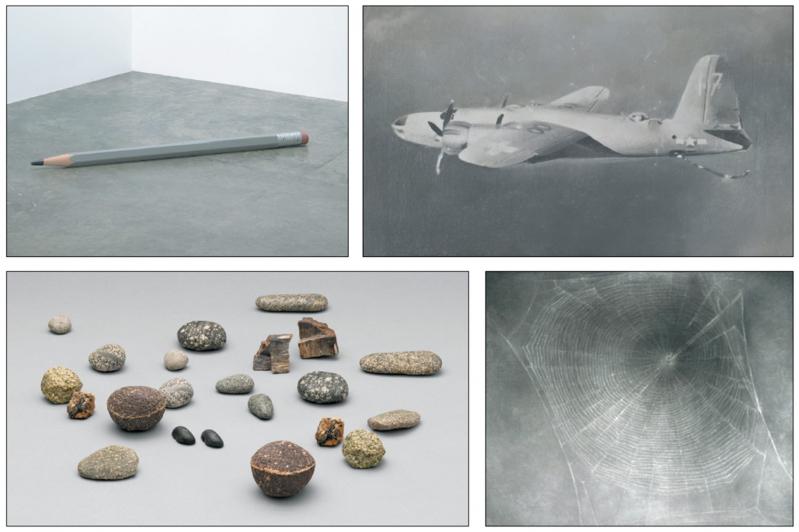

The images she chose were typically violent or tragic incidents, inspired by the escalation of the Vietnam War and perhaps tied to her childhood experience as a postwar refugee — contemporary or World War II planes on fire or crashing, an “Explosion at Sea,” a “Forest Fire.” A series of transportation images followed, featuring a train, truck, and car. These were all in black and white, which gave them a cooler distance, but she rendered some paintings during this time in color. “Freeway,” an atypical employment of illusionistic space and classical perspective, is subdued and overcast. A sculpture, “House 2,” and the painting “Burning Man” have fiery reds and glowing yellows. Giant sculptures of a pencil and pink erasers are further evidence of her combining painting and sculpture during this period.

By 1968, she abandoned painting in favor of pencil drawing on an acrylic ground. In a new series, she renders in pencil replicas of photographs and other printed images. Some continue to have dire connotations, such as “Hiroshima,” “Airplane Disaster,” and “Zeppelin.” Yet others return to the mundane objects of her first explorations, in this case, letters and a photo of a moonscape.

The fourth floor begins with her ocean drawings from photographs she took of the Pacific near her studio in Venice Beach. For about a decade beginning in 1968, her barren backgrounds came to be flooded with imagery. Her new compositions filled each page, stopping just short of the borders. In this way, she underlined the object-ness of these drawings. The endless ripples on the surface lacking a horizon, land mass, or any other reference point rendered the subject as flat as its surface, converting realism into the abstract.

Ms. Celmins continued to use this approach for years to come, expanding it to the night sky, the surface of the moon, and the desert across multiple mediums that have included graphite, charcoal, oil paint, and several printmaking techniques.

This representation of an artist in full allows us to examine in depth every part of her career and the sometimes circuitous route of how each phase spoke to the next, or was a reaction to the previous or the beginning, and so on. An early intention to take evidence of her hand out of her work can be seen in its fullest realization in the “Night Sky” paintings from the 1990s and early 2000s, in which the canvas is painted and sanded, then painted and sanded again, building up a rich, brushless surface.

“To Fix the Image in Memory I-XI,” the sculptural piece from which the show takes its name, and a much later piece called simply “Two Stones” are unusual extensions of her imagery out from the picture plane and into the third dimension. Found objects, in this case desert rocks, were used as models to cast in bronze and paint to match them. In the first piece, dated from 1977 to 1983, there are 11 examples, as indicated in the title. Each stone and its effigy are placed next to or near each other, urging the viewer to “look and look again,” one of the artist’s regular exhortations.

One cannot help but study each piece to discern the subtlest contrasts and clues as to which is which. Some are easier to place than others, but even with the originals and copies determined, the group of objects continues to fascinate. Both pieces date from what is presumably the finding of the rocks in 1977 but continue to the casting and painting of their twins, in the latter case from 1977 to 2014-16, another nod to the conceptualism at the heart of Ms. Celmins’s work.

As the organizers note, her painting of the stones marks her return to the medium in the early 1980s, interrupted for a time by charcoal in the 1990s, but a constant throughout the rest of her career.

The later years seem a kind of “eternal return” to original and older themes. These have been reinvigorated with new discoveries such as her “Spider Webs” and “Blackboard” series, each an “invitation to look harder than you would look normally,” something she hopes inspires “a double take . . . and maybe a little smile comes out of it.”

There are many opportunities to marvel and even smile in this exhibition, a testament to the success of its creator. It will remain on view through Jan. 12.