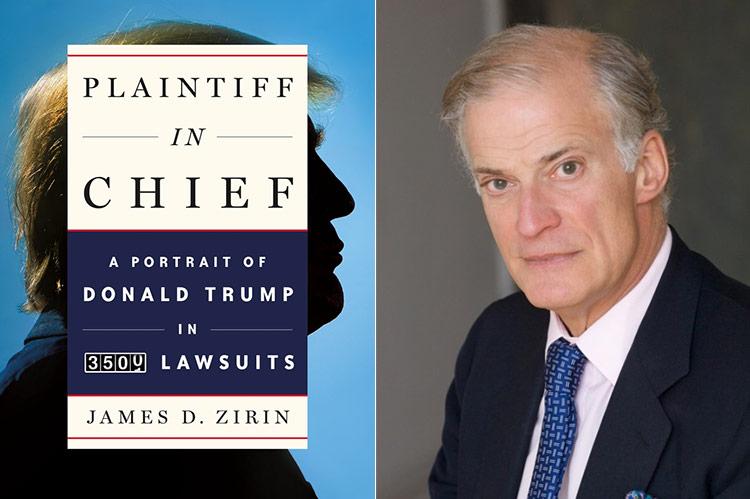

“Plaintiff in Chief”

James D. Zirin

All Points Books $28.99

In his very first court case, a 27-year-old Donald Trump denounced as “outrageous lies” the allegations that his father’s real estate empire in 1973 was violating the federal Fair Housing Act at 39 apartment buildings in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island. He also announced a $100 million counterclaim for sullying the Trump name, and later through his lawyer smeared a young Justice Department Civil Rights Division attorney named Donna Goldstein for overseeing “Gestapo-like interrogation” and “descending upon the Trump office with five storm troopers.”

Sound familiar?

Mr. Trump’s lawyer, mentor, and defender then and long after, you may recall, was the notorious, reptilian Roy Cohn of McCarthy hearings infamy, from whose legal rules of the road Trump the Younger has done his best (or worst) to follow: Never Surrender, Never Settle, Counterattack, Countersue, and Always Declare Victory. Though settle Mr. Trump often had to do.

“Where’s my Roy Cohn?” Mr. Trump as president has reportedly cried as troubles mount.

Those tactics, as the lawyer/author/journalist James D. Zirin reminds us, worked to delay resolution of the F.H.A. case for years. But, in the end, claims against the government and Ms. Goldstein were dismissed (she became a respected Los Angeles Superior Court judge), and Mr. Trump did agree to a typical slap-on-the-wrist settlement: to avoid future discrimination and buy a two-year series of For Rent newspaper ads touting “Equal Opportunity Housing.”

Still, Mr. Trump claimed victory, citing the settlement’s boilerplate language: “without admitting or denying guilt.” But investigation of discrimination at Trump properties continued into the early 1980s.

In “Plaintiff in Chief: A Portrait of Donald Trump in 3,500 Lawsuits” (a figure for which the author credits Newsday, while noting that the American Bar Association reckons 4,000), Mr. Zirin promises a special “window into his nature, temperament, and methods” — “scorched earth” tactics but actually a less than stellar win-loss record: “40 years in which he abused the power of the lawsuit, mostly with little success in court but with remarkable success in attracting attention to himself, as well as the ‘Trump’ brand.”

“This pattern of behavior,” says Mr. Zirin, “will present some insight into his conduct in office in which he seeks public approval by attacking his critics and then portraying himself as the victim of a political witch-hunt, more sinned against than sinning.”

True enough. And Mr. Zirin paints that pattern in sharp detail — Mr. Trump’s often contentious real estate dealings, legendary unpaid debts, unsuccessful casino gamble in Atlantic City, the Trump University fraud, and boorish misogyny.

But, frankly, there is also something a bit incongruous, even uncomfortable, about picking through the complexities of these long-ago legal encounters while day after day we witness how much further Mr. Trump as president can go — carelessly compounding crises overseas, paving the way at home for perhaps the most dramatic trial in American history, in the U.S. Senate, over his own impeachment.

Still, Mr. Zirin comes naturally to his interest and expertise on the legal, illegal, and anti-legal aspects of our current commander in chief, having served more than 50 years as a trial attorney and federal prosecutor.

His father was a New York trial and appellate lawyer, and “most of my parents’ close friends were lawyers and judges [who] gathered at our house to discuss interesting cases in court.” His wife’s grandfather David T. Wilentz prosecuted the 1935 Lindbergh baby kidnapping and killing case.

Accordingly, Mr. Zirin was “astounded” and “outraged” by Mr. Trump’s “war against the courts, the judiciary, and the Justice Department, as well as basic constitutional values,” his calls for a Muslim ban, his demonizing the free press as “enemy of the people,” and such.

But one can contest Mr. Zirin’s argument, understandably reflecting a lawyer’s bias, that Mr. Trump’s “bullying techniques” in and out of court “catapulted him to the summit of the American political system.” More important, one might suggest, was Mr. Trump’s weaponization of celebrity, the stagecraft, screencraft, and marketing magic he mastered through his reality TV show, “The Apprentice,” and the sense he developed of a polarized, disgruntled America that would become his base, its values, desires, and prejudices to which he so successfully plays.

Indeed, before his election, Mr. Trump’s sharp legal and financial practices made him so mutuum non grata that only a few institutions would risk lending. Most notable was Germany’s Deutsche Bank, subsequently fined for laundering funds from wealthy Russians of just the sort also funneling small fortunes into Mr. Trump’s condos, which now only raises more questions about his Moscow connections, inclinations, maybe obligations.

Perhaps recent court rulings that a president must reveal his tax returns to duly authorized legislators and investigators will ultimately answer those questions. But that trail leads to a Supreme Court now more politically tilted than ever in recent memory, thanks to Mr. Trump himself. So, to quote him, “We’ll see what happens.”

“Trump’s ego led him to throw caution to the wind” in the Atlantic City casino venture that became a multimillion-dollar disaster, Mr. Zirin maintains. “He craved the limelight, and the casino business, with its annexed hotels bringing with it popular entertainment, busty showgirls, sporting events, celebrities, media coverage, flash, and glitz, was perfect for him.”

But it’s not hard to imagine that the darker force of organized crime, with which Mr. Zirin reports Mr. Trump worked comfortably, if deniably, on New York construction, also pushed him to help generate a mob cut from the Jersey projects, even if Mr. Trump had privately suspected he’d lose his own big bet on betting.

“If anyone taught Trump that it was legally possible to treat women like shit,” Mr. Zirin writes, “it was Cohn” — a homosexual who died of AIDS, though not before being disbarred for “reprehensible conduct” despite a defense mounted by a former federal judge, Harold R. Tyler Jr. (And, though not mentioned, by a former federal prosecutor, Michael Mukasey, later U.S. attorney general, now an East Hamptoner and, earlier, my college roommate.)

But Mr. Trump was “first, last, and always a womanizer,” we are reminded — with at least 16 complaints of sexual misconduct against him at the time he took office, including one involving a woman working on his campaign. Only one, by Summer Zervos, a contestant on “The Apprentice,” has become a pending court case, with a New York State Appeals Court last March rejecting Mr. Trump’s bid to halt her suit for defamation after Mr. Trump called her a liar.

And then there are the two famous pre-election payoff cases — $150,000 by the then-Trump-supporting National Enquirer to “catch and kill” the Playboy centerfold model Karen McDougal’s tale of a yearlong affair in 2006-7, and $130,000 apparently by Mr. Trump himself (through his now-jailed lawyer Michael Cohen) to squelch the claims by the porn star Stormy Daniels of similar adultery about the same time.

The House Judiciary Committee in September reportedly decided to question both women about those payoffs as possible campaign finance violations “in coordination with and at the direction of” Mr. Trump, Mr. Cohen has testified.

Meanwhile, the Manhattan district attorney’s office has sent subpoenas to the Trump organization’s accounting firm for eight years of Trump taxes in its investigation of the Daniels payment as a violation of state law. And this month a federal judge, Victor Marrero (appointed by Bill Clinton), smacked down the claim by Mr. Trump’s corporate lawyers (including former A.G. Mukasey’s son Marc) that a sitting president could not be involved in any type of “criminal process” because it would “distract him from his constitutional duties.”

“Bared to its core, the proposition the President advances reduces to the very notion that the Founders rejected at the inception of the Republic, and that the Supreme Court has since unequivocally repudiated: that a constitutional domain exists in this country in which not only the President, but, derivatively, relatives and persons and business entities associated with him in potentially unlawful private activities, are in fact above the law,” wrote Judge Marrero. “Because this Court finds aspects of such a doctrine repugnant to the nation’s governmental structure and constitutional values, [it] DISMISSES the President’s suit.”

Again, the Supreme Court could say otherwise. And Mr. Zirin notes the majority legal view that pre-presidential activities cannot be considered grounds for impeachment. But those tax returns could shed unflattering light on far more than Mr. Trump’s extramarital escapades.

In that narrow respect, however, given Mr. Trump’s incorrigible womanizing as a young man, husband, and father, it’s noteworthy that there have been no reports of sexual improprieties since his election. Could he really have broken such a lifelong habit now — with all the awesome power and appeal of the presidency?

Could official security details be preventing new bad behavior, or secretly enabling it, as in the Kennedy White House? We await more whistle-blowers — if that term, in this context, is not too vulgar.

As for impeachment itself, Mr. Zirin sees the political danger for Democrats in voting articles that the Senate would not pass, in essence declaring him not guilty and surely energizing his base.

Of course the author could hardly have imagined the phone call with a Ukraine president desperate for mysteriously stalled U.S. military aid, including Mr. Trump’s Mafia-style mandate (“I would like you to do us a favor, though”) for investigation of Joe Biden and his son, arguably attempted extortion through misuse of Oval Office power for political purposes.

But Mr. Zirin would not be totally surprised by that, or by Mr. Trump’s subsequent weakening in the polls.

Toward the end of “Plaintiff in Chief,” he writes: “We all watch anxiously for the next shoe to drop, the next salacious fact to emerge, the next dollar to be wired to or from an LLC bank account, the next traditional ally to be trashed, the next cabinet member to be fired or hired, the next ‘great’ deal to be announced only to find there is no deal at all.”

“In 2020,” he hopes, “the American people may find Trump’s conduct in office so grotesquely repugnant to presidential norms that they refuse to return him to power.”

And then it may well be a viciously angry, unpredictable complainer in chief and his unconscionable hints at civil war with which we’ll all have to deal.

David M. Alpern, a former reporter, writer, and senior editor at Newsweek, interviewed Donald Trump during 32 years as host of the “Newsweek On Air” (later “For Your Ears Only”) radio show. Most recently he moderated monthly discussions on foreign policy for the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor, where he lives.

James D. Zirin’s previous book was “Supremely Partisan,” about the Supreme Court. He has a house in East Hampton.