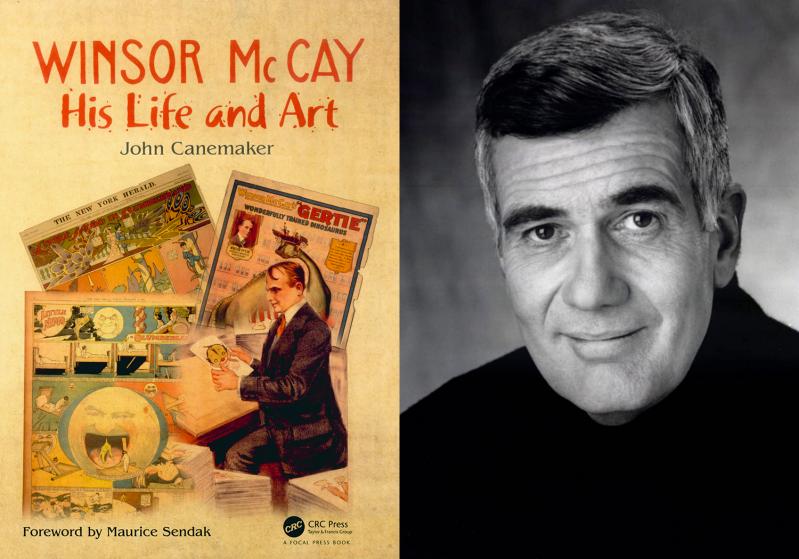

“Winsor McCay: His Life and Art”

John Canemaker

CRC Press, $59.95

Like Mel Blanc, who gave multitudinous voice to the Looney Tunes, or even Walt Disney, Winsor McCay was a uniquely American genius, up from nothing, out of nowhere, self-taught, and propelled by an immense imagination.

Primarily a newspaper cartoonist, McCay in fact beat Disney to the punch in the nascent field of animation, introducing “Gertie the Dinosaur” in a 1914 vaudeville act in Chicago, the artist (“James Cagney with a forelock”) live onstage issuing commands to the animated diplodocus, who seemed to hear and reluctantly obey in the midst of her childlike antics, before McCay joined her onscreen as an animated figure, Gertie lifting him onto her back, and they rode off together.

“Not until the Walt Disney studio hit its stride in 1934 (ironically, the year of McCay’s death) would the animated cartoon match the high-quality draftsmanship and naturalistic motion established two decades before in ‘Gertie the Dinosaur.’ ”

So writes John Canemaker in “Winsor McCay: His Life and Art.” Out recently in a glossy coffee table format, it revisits, corrects, and expands upon biographical work the author did in the 1980s. Mr. Canemaker, a Bridgehamptoner when he’s not heading up the animation program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, isn’t just the country’s pre-eminent scholar of animation, he’s a practitioner, winning a 2005 Oscar for his animated short “The Moon and the Son.”

Here he details the trajectory of an artist with “an absolute craving to draw pictures all the time,” as McCay himself once put it. He got his start painting posters for traveling circuses and so-called dime museums, in particular the Wonderland in Detroit, which “combined aspects of vaudeville, funhouses, and circus midway freak shows under one roof.” One such museum in Cincinnati introduced him to the Armless Wonder, Joe-Joe the dog-faced boy, and the What Is It, gnawing on a thighbone.

A “lifelong fascination with the grotesque” would stay with McCay, and “appeared as a leitmotif in all his later works,” most memorably in his witty strip “Dream of the Rarebit Fiend,” which first appeared in The New York Evening Telegram in 1904, offering “a decidedly adult point of view and an anticipation of surrealist conceits in its juxtaposition of fantastic occurrences in mundane settings, the instability of appearances, and the irrationality of life.”

Among the “Rarebit” strips reproduced in this volume, we see a sleeping man slowly suffocated by birds and small mammals that gather at his mouth, a teddy bear that comes to full-grown life to devour an infant and attack its parents, and a burial of a supposedly dead man who remains alive enough to hear himself bad-mouthed by his pallbearers and wife before the dirt falls, seemingly on the reader, who is stuck in a corpse’s-eye point of view. All in the Sunday funnies, mind you.

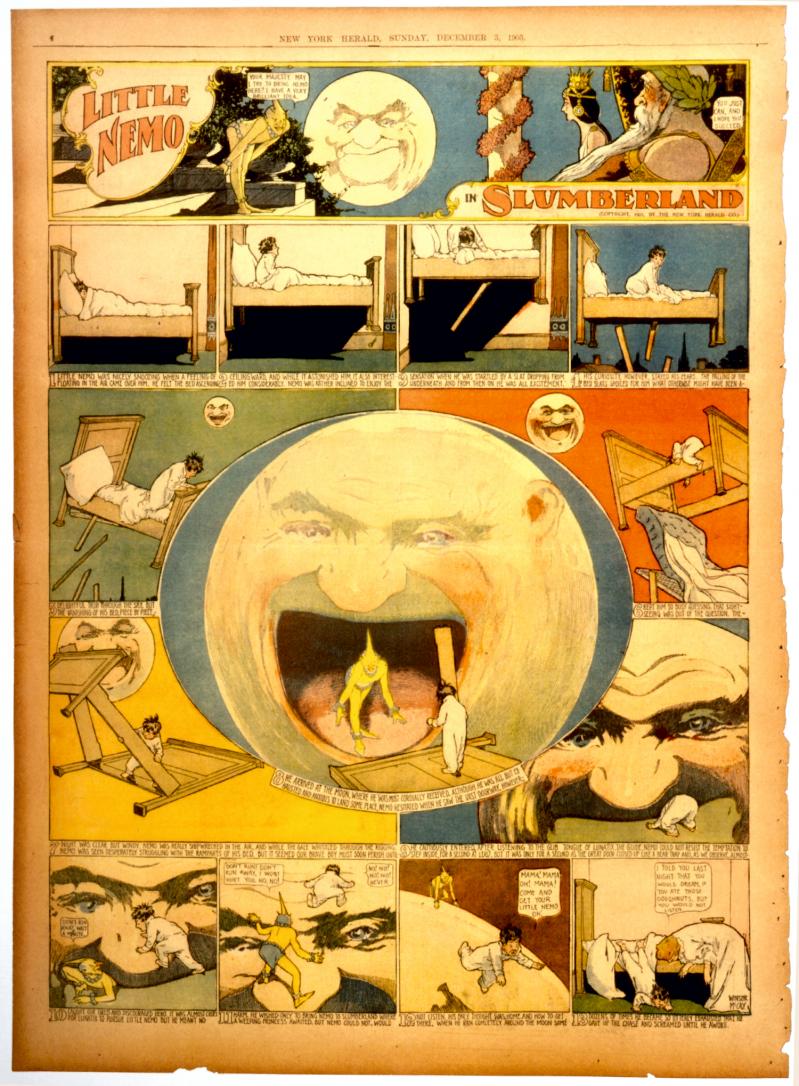

The nightmares in these strips end with the subjects waking up in horror, a motif McCay would also use (the waking, anyway, in dazed bewilderment) in his masterpiece, “Little Nemo in Slumberland,” which Mr. Canemaker describes as “a child’s version of the mythic theme of the quest, set in a dream world,” and “quite simply the most beautiful and innovative comic strip ever drawn.”

It first appeared in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Herald in 1905, its success helping to make McCay famous and rich — factoring in vaudeville performances and royalties from licensing and merchandising, by 1914 he was earning somewhere close to $100,000 yearly, with showplace homes in Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn and Sea Gate, near Coney Island.

McCay — as the author points out, bohemian turned bourgeois, a fantasist who later promoted a social conscience, a private man who shut himself away for hours to work in solitude yet who loved the stage — was undone by a combination of his own admittedly terrible business sense, his being browbeaten into political editorial cartooning, marital stress, and plain old exhaustion.

Of course there’s another contradiction in the reverence with which the cognoscenti regard the work of “the first master of two new art forms,” while his name shrinks into obscurity.