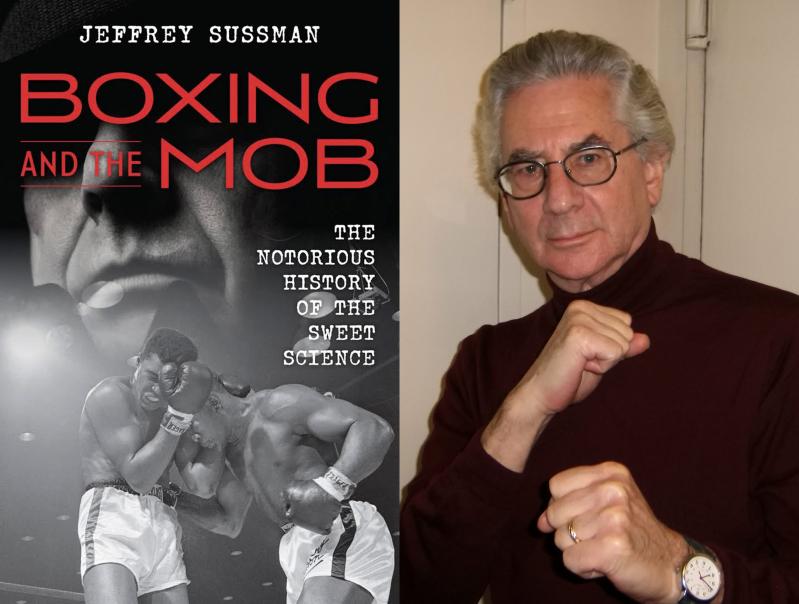

“Boxing and the Mob”

Jeffrey Sussman

Rowman & Littlefield, $34

After Cassius Clay, soon to be anointed Muhammad Ali by the Nation of Islam, became heavyweight champion, the boxing industry panicked at the possibility of a religious organization replacing the rightful rulers of boxing, organized crime. Under the mob, fights had been fixed, boxers exploited, officials bribed and intimidated. When necessary, legs had been broken. Could the sweet science depend on Muslims to govern the slum of sports with such authority?

Eventually, Don King would emerge to crack the whip, his credibility as a convicted killer as powerful as any Mafioso. But as a rookie boxing reporter, I remember the anxious time when the future was unclear. There were hearings and editorials calling for a federal boxing czar, at least a central government like that of every other major sport (boxing was one, then), but underneath was a certain nostalgia for the days when Owney (The Killer) Madden could call on his childhood fellow delinquent, the actor George Raft (né Ranft), to slip a tranquilizer into the champagne of a fighter they had bet on to lose.

This is the world that Jeffrey Sussman calls up in his “Boxing and the Mob.” Stylistically, Mr. Sussman is what in boxing would be called a “banger,” less dependent on finesse than straight-ahead slugging, a technique that works well enough for pounding through a gamey half-century of brutality, fake news, and the romance we attach to outlaws.

I arrived toward the end of the era, but in time for a taste. At a Las Vegas fight, big enough for the press agents to dole out cash-stuffed brown envelopes and hookers to major reporters and columnists (at The Times we were forbidden to accept any gifts), there was consternation when one pundit of pugilism reported that his wallet was missing after a sleepover. Was this the apocalypse, had the so-called Mustache Petes lost their grip?

When word was eventually spread that the wallet had been found and the miscreant disappeared, there was relief mixed with the disgust; the universe was still in order. As with most tales of boxing and the mob, it is still not clear to me how much of this story is true.

But gangster-dominated boxing, as Mr. Sussman makes clear, was a nasty business. The likes of Madden, a protégé of Arnold Rothstein, who fixed the 1919 World Series, his henchman, Abe (Little Hebrew) Attell, a former fighter, and the mobsters Frankie (Mr. Gray) Carbo and Blinky Palermo controlled the arenas, the promotions, the commissions, the managers, and the fighters, taking a cut from each and betting on sure things. Not unexpectedly, the odious Roy Cohn comes in for a cameo.

The victims were always the fighters. Their savings, their futures, their minds were ripped off by criminals allowed to operate by politicians, bankers, and the slumming gentry who satisfied their homoerotic bloodlust at the fights. Feeling guilty, I always bought the ties one former contender, now punch-drunk, peddled in the lobbies of fight hotels.

Fighters felt trapped in the system. The vaunted Jake LaMotta would never have been given the chance to fight for and win the middleweight championship if he hadn’t first taken a dive (for $100,000) on an earlier fight. He was paying dues to the mob. Later, according to Mr. Sussman, he compared the treatment of boxers to that of whores, selling their bodies until they were discarded.

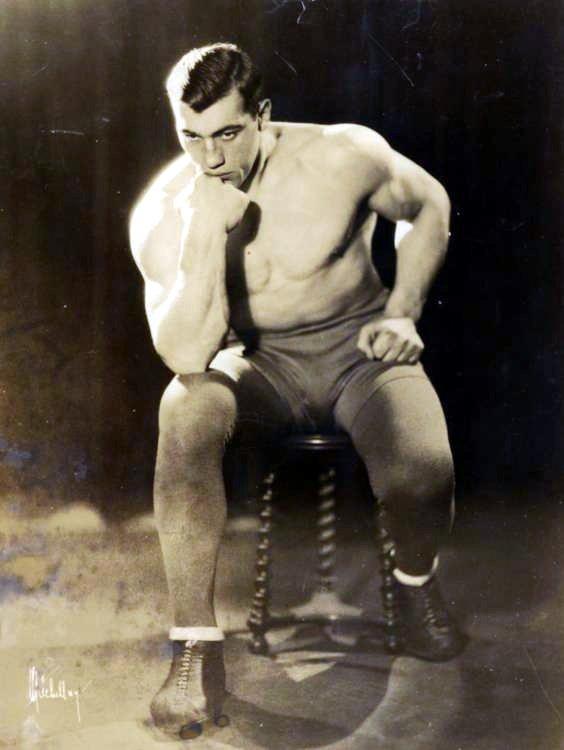

The prototype was Primo Carnera, a genial 6-foot-7 circus strongman who spoke little English (best remembered as the inspiration for Budd Schulberg’s “The Harder They Fall”). He fell into the hands of Madden and Raft, who guided him through a series of fixed fights toward Max Baer’s heavyweight championship. The so-called “Ambling Alp” actually thought he could fight, watching his opponents take dive after dive. His boxing career ended when Baer rejected Madden’s bribe and beat Carnera helpless. The mob faded away. Baer paid Carnera’s hospital bill and helped set him up as a successful wrestler.

The most interesting character in the book is Sonny Liston, well covered elsewhere. Liston was mobbed up, and his past was littered with suspected dives, his and others. Yet he was also, unquestionably, one of the great fighters of his time. I found him scary, yet oddly poignant. Liston was the second youngest of an Arkansas sharecropper’s 25 children. He made his way to St. Louis, where he became a mob enforcer. He learned to fight in prison.

I was ringside at both his fights with Clay/Ali and can only agree with Mr. Sussman’s absolute uncertainty over whether they were fixed. A huge favorite to retain his title in 1964, he lost that first fight with Clay by refusing to come out for the seventh round, claiming a dislocated arm. Was that true or had the Nation of Islam threatened him? Was he part of a betting coup? Mr. Sussman reports the rumor that he and the Las Vegas gambler and alleged mobster Ash Resnick had each made a million betting on Ali to win. Of course, such rumors made up for our predictions that Liston would knock out Clay in the first round.

In the second fight, it was Liston who went down in the first round, victim of either the perfect punch or the phantom punch. Who knew what was in his haunted mind? Malcolm had just been murdered, and there were rumors of more killings to come. What moral standard had he pledged to uphold? His death at 39 or 41 or 43 (even his age was not certain) was considered a mob hit, somehow boxing related.

Mr. Sussman has dug up an all-star roster of low-life scum for our reading pleasure, but these days that mob doesn’t look so bad compared to the ones we have chosen. At least there was some style.

During the Senate boxing hearings in 1964, I rashly opined that Liston’s pal Resnick, whom I described as a good-looking gangster hanger-on, should be banned from boxing. Weeks later, in a dark Las Vegas parking lot, three men surrounded me and pushed me up against a car. One of them got close enough for me to smell his cologne. It was Resnick. He said, “Good looking, huh?” He smiled and pinched my cheek. Chuckling, the three walked off into the night.

Robert Lipsyte lives on Shelter Island, where he writes a column for The Reporter. He is the author of “SportsWorld: An American Dreamland.”

Jeffrey Sussman will talk about “Boxing and the Mob” on June 8 at 1 p.m. at the East Hampton Library. He lives part time in East Hampton.