“Assassin of Shadows”

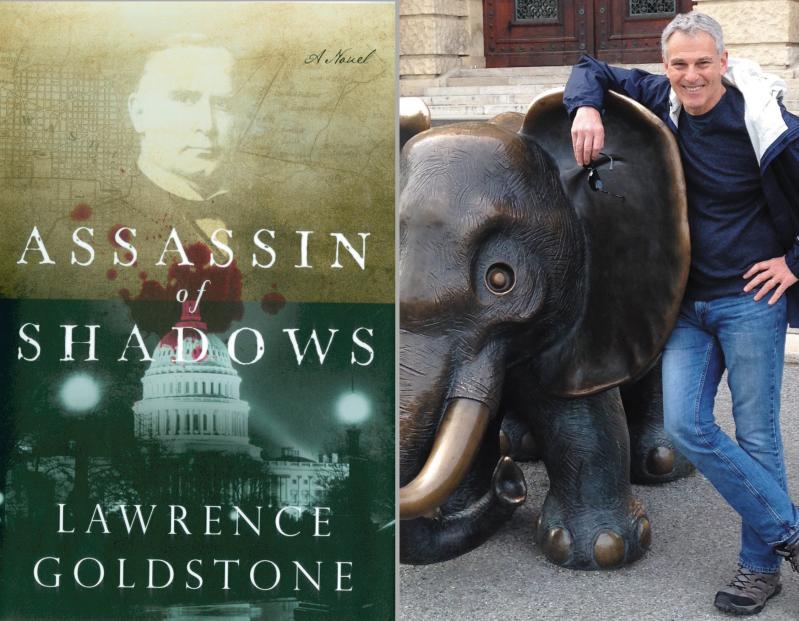

Lawrence Goldstone

Pegasus Crime, $25.95

In 1901, six months into his second term, President William McKinley was assassinated at the World’s Fair in Buffalo at the height of his popularity. At the time of his death, McKinley had led the United States to swift victory in the Spanish-American War and delivered the country out of an economic depression into years of prosperity. A Civil War veteran, a kindly friend and colleague, widely considered an effective president, he nonetheless had enemies among an impoverished working class, many of whom identified with a growing anarchist movement.

Yet, in what was considered an open-and-shut case, McKinley’s assassin acted alone. Or did he? In his new novel, “Assassin of Shadows,” Lawrence Goldstone offers an alternative theory.

A prodigious historian, Mr. Goldstone is drawn to fiction when incidents from our past leave questions open. In his novels “Anatomy of Deception” and “Deadly Cure,” he took readers on a metaphoric car chase through the real world of medicine at the turn of the last century, weaving in fictive elements and characters. In “The Astronomer,” science and church clashed after an imagined murder in 1534.

“Assassin of Shadows” is essentially a police procedural with a bouquet of credible theories that keeps the characters jumping. Was the assassin the anarchists’ dupe? Set up by dirty cops? An instrument of the vice president’s ambition? Or just a guy with a beef and nothing to lose?

At the heart of the story is a Secret Service operative, Walter George, a lovable mug of a guy who will stop at nothing to keep a plot line going. It’s worth knowing that prior to McKinley’s assassination, the Secret Service was tasked with routing out counterfeit U.S. currency, as well as safeguarding the president in public. In the opening scene, in which we first meet Walter — a bearded, beefy, giant of a man — we assume he is the henchman for a ring of Chicago counterfeiters on the lam. In fact, Walter is embedded Secret Service, inexplicably using his real name, in a sting operation that shows just how far he is willing to go.

There’s no rest for the weary. Walter is soon joined by Harry Swayne, nominally his boss, though, we’re given to believe, his intellectual junior. “Go home and pack a bag. . . . McKinley’s been shot. There’s going to be a big investigation,” says Harry, with apparent glee. “We’re heading it.”

McKinley survives Leon Czolgosz’s point-blank bullets to the chest and stomach, only to die of gangrene eight days later.

“I done my duty,” offers Czolgosz, a self-described anarchist, on his immediate arrest. Buffalo police swiftly round up anarchists, including the movement’s “high priestess,” Emma Goldman, in what Walter calls “a conspiracy to find a conspiracy.”

In real life, Czolgosz was swiftly brought to trial, convicted, and executed within two months of McKinley’s death. If he had secrets, they were buried with him, which opens the field for speculation in “Assassin of Shadows.”

Walter initially suspects that Czolgosz acted alone, which he sets out to prove, effectively bucking “the system” he routinely holds in contempt. But soon our hero stumbles over real-life inconsistencies that give him pause. For instance, how could McKinley’s two experienced Secret Service operatives have allowed the assassin to get so close, failing to notice the suspicious bandage that concealed his gun?

The cops in “Assassin of Shadows” are largely morons, on the take, philandering, or seeking political gain; the trick is to figure out which is which and keep them straight. As Walter observes, the after-the-fact show of force on the part of the cops is always most impressive after a debacle. They clash with the Secret Service as a matter of course, showing their disdain for Walter and Harry in droll, sarcastic lines, along with sophomoric acts of non-cooperation.

Walter’s antecedents are the Sipowiczes and Columbos of yore, who appear so average they are easy to discount — at least, at first. Like his forebears, Walter soon reveals his latent superiority. A closet intellectual, he knows what texts have influenced anarchists because he’s read them himself (Proudhon’s “What Is Property?” though not in the French). He is an unsentimental reader of character, given to pronouncements such as “There are two kinds of trust. You can trust someone to be honorable or trust them to be predictable.” He impresses the good guys and the bad with his independence, a trait that marks him for either a middling career or an early grave. No matter, Walter is too dedicated to finding the truth to give a damn.

Mr. Goldstone’s brisk, often witty prose cuts right to the chase. He sets a scene with an authority that airlifts the reader in, leaving no doubt that he hasn’t veered far from the facts. The Cincinnati community from which Czolgosz hails is “a tumble-down neighborhood of immigrants and laborers; of families squeezed into tiny apartments; of the mixed smells of cooking fat, spices, and unwashed humanity . . . where commerce was conducted by raised fingers in barter. . . .” Here, radicals grow “like so many stalks of wheat, just waiting for the Emma Goldmans to happen along with a scythe,” observes Mr. Goldstone, with an evocative metaphor.

Likewise, in describing his cast, Mr. Goldstone works like a caricaturist, homing in on salient physical qualities. Czolgosz’s father is “a man every inch of whose body had received abuse or injury in pursuit of an adequate wage.” Mark Hanna, a powerful businessman and politician who propelled McKinley into office, has a head “dominated by ears that seemed to stretch from crown to jaw and a bulbous nose.” A sergeant in the Buffalo police headquarters is a “ruddy-faced fellow whose bovine neck bulged over his uniform collar.”

For all Mr. Goldstone’s skill, his story lacks the requisite suspense because of what I’ll call the McKinley Effect. On the president’s assassination, the country reeled in shock and truly mourned. However, the memory of McKinley was soon overshadowed by the ascension of Vice President Theodore Roosevelt to high office. In a splashy early act, T.R. took over the construction of the Panama Canal — the engineering marvel of its time — from the French, a move that was under debate during the McKinley years. McKinley was all but forgotten in the roar of T.R.’s personality.

Even the theory that T.R. orchestrated the assassination, which gets considerable play in “Assassin of Shadows,” fails to raise the stakes. It’s hard to invest fully in the outcome when the historical victim left an indistinct mark on public consciousness.

Nonetheless, there’s fun to be had in “Assassin of Shadows,” as well a romantic subplot that bumps along. Walter, against all odds, turns out to be something of a blushing ladies’ man. Harry’s widowed sister Lucinda longs for Walter to shave off his gnarly beard and succumb to a regimen of her home-cooked meals. Naturally, she is a beautiful woman, with chestnut hair, big eyes, and “full lips with a cupid’s bow in the center” — i.e., the Gibson Girl looks that were prized at the time.

Harry seconds the motion, peppering Walter with invitations to dine. But Walter is distracted by a quietly sexy anarchist.

With its mix of fact and fiction, of real-life characters with the imaginary, “Assassin of Shadows” propels the reader back to the history. Interestingly, the times were not unlike our own: social upheaval resulting from technological change, working-class strife, tensions between progressives and champions of the status quo, all of which provide rich context here. Mr. Goldstone resists coming to the predictable conclusions these conditions suggest, however. A wholly surprising outcome dovetails neatly with early-20th-century headlines.

As baffling as the phenomenon of Walter’s sex appeal or the mysteries behind the president’s assassination might be, it’s the novel’s title that’s the true puzzler. What does it mean, if anything? “Assassin of Shadows” sounds like a syntactical error, better suited as the name of a video avatar or a dangerous new cologne from Calvin Klein.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor at the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” a book about history’s great romantic women. She lives in Springs.

Lawrence Goldstone lives in Sagaponack.