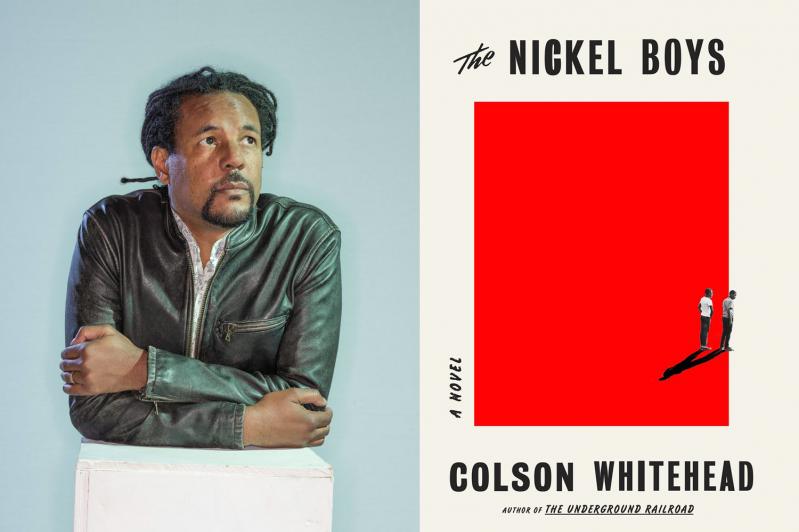

“The Nickel Boys”

Colson Whitehead

Doubleday, $24.95

Based in large part on the true story of a Florida reform school where wayward boys, black, white, and Latino, were to be transformed into young men “useful” to society, “The Nickel Boys” follows the life of Elwood, an optimist raised by his grandmother who listens to a record of a Martin Luther King Jr. speech over and again on her turntable, who wants to change the world, who thinks about the politics behind busing and lunch counter boycotts, and who is certain justice can be won. Elwood is the purest of the pure. A character so strong, so smart, so correct.

The reason why Elwood, who was college-bound on the day his life plummeted into disintegration, so unjustly ends up in this hell-on-earth place is a heartbreaking revelation in this slender novel. And that’s where Elwood meets Turner, a pragmatist who will guide him through many, but not all, of the intricacies of dealing with cruelty.

Colson Whitehead’s last novel, “The Underground Railroad,” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award for its investigation into Civil War-era freedom attempts. “The Nickel Boys” shows us how little a difference a century made.

Today forensic archaeologists continue to unearth the graves of boys, black and white, who “disappeared” into the Florida “reform school” system, each discovery representing vicious, bloody beatings, privation. All at the hands of angry, greedy hypocrites. Newspaper and NPR accounts report that the men who made it out alive have been tormented by a lifetime of nightmares.

The Florida School for Boys, also known as the Arthur G. Dozier School for Boys, operated a 1,400-acre campus from 1900 until 2011 in Marianna, Fla., near Tallahassee, and the school had a second campus near Okeechobee opened in 1955. For a very long while the facilities were the largest reform schools in the country. On the Marianna grounds, some 100 deaths were documented, but there were 55 burials outside the actual cemetery.

After abuse allegations from the U.S. Department of Justice, as well as Florida law enforcement, the facilities closed. But when asked in the 2000s to have the bodies exhumed, the State of Florida demurred. DNA matches be damned. The state wanted to sell the property. Relenting, the state asked University of Florida archaeologists to investigate. In 2017 Florida held a formal apology ceremony. Indeed, as of this very week, forensic workers have been summoned back to examine more sites at the Okeechobee land, where there are possibly 27 additional unmarked graves.

Most of the brutalized boys, now men, who feel they can come forward with their stories are white.

Oh, how much the writing in “The Nickel Boys” holds back while walloping home the message. Mr. Whitehead’s sentences are simple, straightforward. Which of course makes the horror behind every event more painful. He has ripped out every unnecessary word or description. Elision is his weapon of choice. Reading attentively, there were several moments when I stopped and asked, “Wait. What just happened?” Only to reread the previous paragraph and realize, “Oh, of course. That was inevitable.”

Mr. Whitehead is a writer who trusts the intelligence of his audience. This technique is indeed the manifestation of reality. Sometimes in real life we have someone who explains to us why one event leads to another. But far more often we must make those connections for ourselves. That was certainly the truth for the Nickel boys.

One of the major scenes in the book is the annual December boxing match between a black and a white “student.” Nickel, the novel’s eponymous former director of the school, was a fighting enthusiast who “maintained a general interest in fitness overall. He possessed a fervent belief in the miracle of a human specimen in top shape and often watched the boys shower to monitor the progress of their physical education.”

“The director?” Elwood asked when Turner told him that last part.

“Where do you think Dr. Campbell got that trick from?” Turner said. Nickel was gone, but Dr. Campbell, the school psychologist, was known to loiter at the white boys’ showers to pick his dates. “All these dirty old men got a club together.”

The “old men” are dirty in plenty of other regards, including the ways they finagle betting on the big fight.

The year when Elwood and Turner were witnessing the events, Griff, “the baddest brother on campus,” with arms like “pistons” or “smoked hams,” was to box Big Chet, who’d come from “a clan of swamp people.” Just before the match, Spencer, the current director of the school, approached Griff and subtly told him to throw the match. Griff didn’t understand. At last Spencer laid it out in plain language. Turner noted that boxing was “crooked as a country preacher.” Yet all the boys held out hope.

Griff was a fighting machine at the beginning of the match. But halfway through all those dirty old men were furious, stomping out, because Griff kept on pounding Big Chet. Until Griff relented. Remembering he was supposed to throw the match. Problem was Griff’s math was off. He’d waited too late.

“They came for Griff that night and he never returned. . . . And if it made the boys feel better to believe that Griff escaped, broke away and ran off into the free world, no one told them otherwise, although some noted that it was odd the school never sounded the alarm or sent out the dogs. When the state of Florida dug him up fifty years later, the forensic examiner noted the fractures in the wrists and speculated that he’d been restrained before he died, in addition to the other violence attested by the broken bones.”

Even in reform school Elwood persists in writing letters to the editor of a progressive newspaper about the injustices he sees. (Yes, despite innocence he has been bloodily beaten at Nickel.) He hears nothing back from the newspaper. He knows he can’t send his letters to be forwarded by his grandmother. She would rip them up as being too antagonistic. And what does he posit? His enormous heart dictates that there are so many letters of outrage on the same subject as his regarding what is incorrect, what is wrong, that the editors don’t have room for one more — his.

On work detail, essentially pro bono for a family in town, Elwood and Turner engage in a philosophical conversation.

“You’re getting along. Ain’t had trouble since that one time. They going to take you out back, bury your ass, then they take me out back, too. . . .”

“You’re wrong, Turner.” Elwood tugged on the handle of a weathered brown trunk. It broke in half. “It’s not an obstacle course,” he said. “You can’t go around it — you have to go through it. Walk with your head up no matter what they throw at you.”

“I vouched for you,” Turner said, wiping his hands on his trousers. “You got ticked off and need to get it off your chest, that’s cool.”

But Elwood’s “thoughts prowled and roved after midnight.” He was seeking justice. And Turner was trying to protect him from harm.

How can what happens at the end of this novel be possible? (This is an anti-spoiler alert.) Oh no, the reader exclaims.

But of course. Everything was inevitable. Mr. Whitehead’s skill at elision is extraordinary.

Lou Ann Walker is the director of the Stony Brook Southampton and Manhattan M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature. She lives in Sag Harbor.

Colson Whitehead has spent many summers in Sag Harbor, where his family has a house. He’ll read from “The Nickel Boys” at the Unitarian Universalist Meetinghouse in Bridgehampton on Aug. 1 at 6 p.m.