“Exhalation”

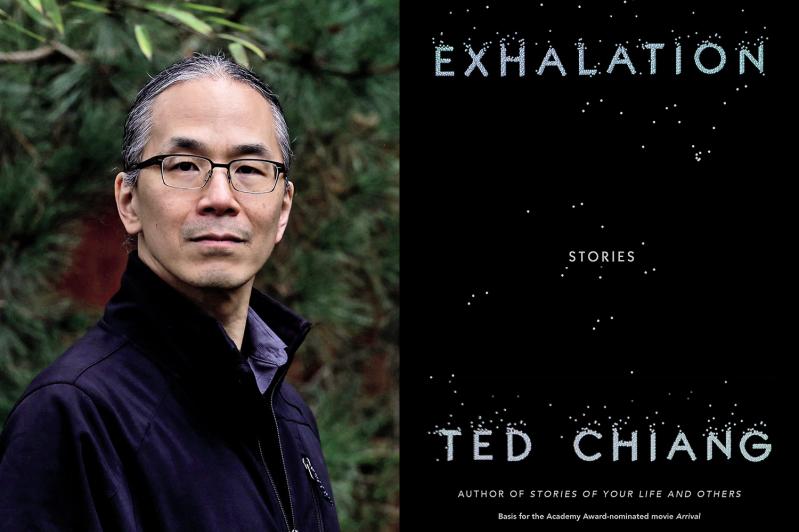

Ted Chiang

Knopf, $25.95

Breaking into the mainstream as a science-fiction writer is a difficult path. Ted Chiang, however, has come about as close as one can get. The 2016 movie “Arrival” is based on one of his novellas, and now he is back with a new collection of stories titled “Exhalation,” which has garnered both glowing reviews and jacket blurbs from no less than Joyce Carol Oates and Colson Whitehead.

Most of the stories in “Exhalation” are set in an America perhaps a few years into the future but nevertheless feel utterly contemporary. Many of them will remind viewers of the television series “Black Mirror,” in that they take current technology and exaggerate it to its logical conclusions, to see where the chips land. And while you can feel the kick the author is getting from inventing inevitable tech “advances,” you sense his ambivalence as he asks both himself and his audience: “What in the hell are we really doing to ourselves?”

In “The Lifecycle of Software Objects,” players adopt an online “digient” — a kind of digital companion — that one “trains” over a number of years to respond in increasingly human ways. Ultimately, some of the players become emotionally invested in their digients. So much so that when the software company goes bust, players scramble to find new games that will host these now homeless entities. Here Mr. Chiang is asking tough questions about digital ethics: If digients have some primitive ability to think and feel, can they simply be abandoned to the digital graveyard?

Norman Mailer once said that the paradox of technology is that it brings “more power and less pleasure.” So it is in Mr. Chiang’s world. In the brief story “What’s Expected of Us,” a small hand-held device seems harmless enough, “like a remote for opening your car door.” You simply press a button after seeing a green flash. Then comes the existential crisis. When users inevitably try to break the rules, the device seems to anticipate the player’s move.

“There’s no way to fool a Predictor,” the narrator writes ominously. Soon the “implications of an immutable future sink in.” Realizing their choices don’t matter, that there’s no such thing as free will, people refuse to make any choices at all. “Like a legion of Bartleby the scriveners, they no longer engage in spontaneous action.” Soon even walking and eating seem superfluous.

The two anomalies in the collection are “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate,” a Borgesian fantasia about mirrors that manipulate time itself, and “The Great Silence,” a short but ingenious story told in the first-person voice of a parrot who wonders why humans are obsessed with the search for extraterrestrial life. “We’re a nonhuman species capable of communicating with them. Aren’t we exactly what humans are looking for?” The narrator speculates that extraterrestrials “conceal their presence, to avoid being targeted by hostile invaders.” (Granted, this is one very smart parrot.) “Speaking as a species that has been driven nearly to extinction by humans, I can attest that this is a wise strategy.”

But near-future technology is closest to the author’s sensibilities. In “Dacey’s Patent Automatic Nanny,” an inventor creates a robot nanny to look after his child. What could possibly go wrong? “He struggled visibly to contain his emotion at seeing what he had wrought . . . a child so wedded to machines that he could not acknowledge another human being.”

And in “The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling,” humans acquire the ability for a digital memory — that is, a database where everything they’ve done or said can be accurately recalled. While this might be good for settling he-said-she-said arguments, the human cost is enormous, including the ability to forgive and forget. “The relationship between those two actions isn’t so straightforward. . . . In most cases we have to forget a little before we can forgive. . . . It’s this psychological feedback loop that makes initially infuriating offenses seem pardonable in the mirror of hindsight.”

It’s worth stating that for all the brilliant technological set pieces, there is not a single memorable character in “Exhalation.” Mr. Chiang even makes a halfhearted stab or two at romance, but falls hopelessly flat. Is this the author’s intent? Is he implying that these characters — who spend most of their waking hours wired to the digital world — are doomed to emotional sterility? Is the title urging us to take a step back from the rapidity of advancement — a deep breath, if you will — till we get our bearings and remind ourselves what it is to be human?

“Man becomes, as it were, the sex organs of the machine world,” warned Marshall McLuhan a half-century ago. “Exhalation” makes us wonder if he was right.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of “Exposure,” a work of speculative fiction that satirizes technology and the media, and the novel “Lit Life.” He lives in Springs.

Ted Chiang grew up in Port Jefferson.