Although Helen Frankenthaler spent some of her formative years as an artist in Springs and East Hampton, she developed a more lasting relationship with Provincetown, Mass., during her marriage to Robert Motherwell. The decade she kept a summer studio there had a profound impact on her work.

An exhibition focused on this second-generation New York School artist’s relationship with the art colony at the very end of Cape Cod will open on Sunday at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill and continue through October.

Her first visits to East Hampton were in the summers of 1951 and 1952, after her initial visit to Provincetown to attend Hans Hofmann’s summer school in 1950. In Springs, she encountered Pollock, who was using unprimed and unstretched canvases he placed on the floor to absorb the black enamel paint he dropped from glass basters. It made a profound impression on the young artist, who was brought to his studio during this time by Clement Greenberg, one of Pollock’s most ardent champions.

Soon, she too was laying unprimed canvases on the floor to absorb the thin paint with which she soaked them. It was a technique she used throughout her career and one she brought to Provincetown as well from 1959 to 1969. She and Motherwell typically spent entire summers there. In 1965, just after their close friend the sculptor David Smith died, the couple took Motherwell’s daughters on a grand tour of Europe instead. That year, they also visited Amagansett briefly.

Motherwell had spent summers in East Hampton in a retrofitted Quonset hut beginning in 1944, but abandoned the area in 1952. The years in Provincetown seemed to define the parameters of their marriage, which lasted from 1958 to 1971.

The end of the Cape inspired Frankenthaler with its landscape defined by dunes, bay and ocean, and scrub pine, its regular traditions such as July 4th parades and her stepdaughters’ lemonade stand, and the flags and banners that waved throughout Provincetown. She spent her mornings working, often after a swim, her afternoons in recreation, and the evenings entertaining.

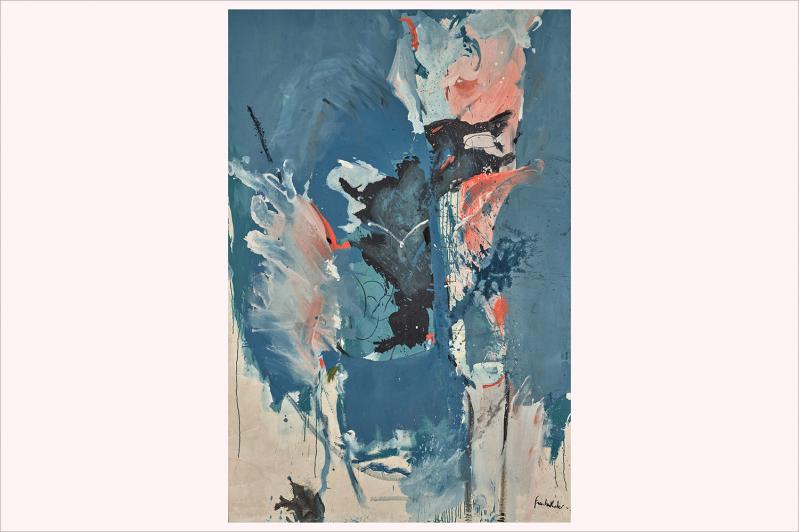

During this period, she had three different studios, and each offered its own stimulus. While what she saw there gave her inspiration, it was filtered through a mind attuned to sensations and what she defined as climates. “My pictures are full of climates, abstract climates and not nature per se, but a feeling. And the feeling of an order that is associated more with nature,” as Elizabeth A.T. Smith quotes the artist in her essay for the exhibition catalog.

This period also marked her move away from the influence of Abstract Expressionist painting to the more fluid approach that would come to define Color Field painting and influence artists such as Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland.

Ms. Smith also sees the effect of the landscape on Frankenthaler’s work, as it “visually and viscerally permeated her thinking, stimulating her work in a variety of ways.” She offers the artist’s insight that “my work is not a matter of direct translations, but something is bound to creep in to your head or heart.”

The exhibition includes 30 paintings and works on paper. Its catalog contains several essays, including one by Frankenthaler’s stepdaughter Lise Motherwell and one by the Parrish’s Terrie Sultan and Alicia Longwell, a timeline, and full-color plates and illustrations.