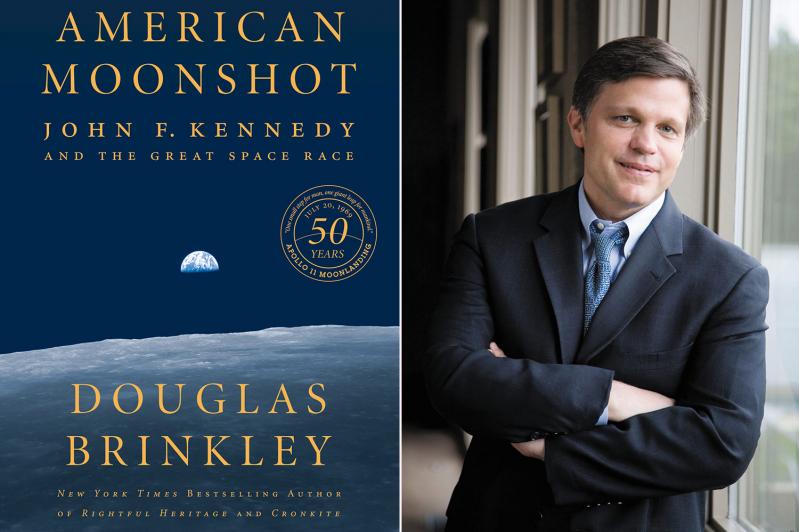

“American Moonshot”

Douglas Brinkley,

HarperCollins, $35

In the Icarus story from Greek mythology, Daedalus fashions wings of wax and feathers so Icarus can escape Crete. A careless youth, Icarus flies too high and too close to the sun, which melts his wings, and he falls into the sea and perishes. The usual takeaways, according to Stanley Kubrick: Don’t fly too high, don’t reach beyond your grasp, keep your aspirations grounded, or always listen to your father.

Kubrick’s takeaway is simple: Make better wings.

With “American Moonshot,” the eminent historian Douglas Brinkley has written a magisterial history of the space age and an affectionate valentine to those brave astronauts who flew to the moon, the politicians who dealt with the art of the possible, and above all to John F. Kennedy. It’s a really superior summer read — a colorful tale of Icarus and Sputnik, a practical tribute to building better wings. And to presidential moxie — defined as “force of character, determination, chutzpah, or nerve.”

“Both the Soviet Union and the United States believed that technological leadership was the key to demonstrating ideological supremacy,” Neil Armstrong said. Both invested enormous resources, had great successes and tragic failures, and produced “competition unmatched outside the state of war.”

But it was Kennedy’s Irish chutzpah and visionary strategy to sell the American public and his political rivals that a capitalistic free-market effort would pay off in worldwide respect for American imaginative engineering and scientific knowhow. James Webb, the NASA administrator, saw the Apollo mission as a potent combo of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Grand Coulee Dam, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the interstate highway system — with maybe the pyramids and the Manhattan Project thrown in as an afterthought.

Mr. Brinkley paints a respectful yet warts-and-all portrait of Kennedy persuading the American public that a Cold War battle could be fought by proxy in space, instead of on the ground. The “lavish investment” funded by American taxpayers would pay off in the end many times over by unifying government, industry, and academia and thereby producing technical benefits: space medicine, radiation therapy for cancer, CAT and M.R.I. scans, personal alert systems, muscle stimulants, satellite reconnaissance, water-purification systems, improved computer systems and weather forecasts, global search-and-rescue systems. Your smartphone and its useful global positioning system, or GPS, owe a huge unseen debt to Kennedy. (And, by the way, to Albert Einstein.)

Kennedy believed that Eisenhower’s wrong-headed views (“Anybody who would spend $40 billion on a race to the moon for national prestige is nuts”) and conservative dillydallying needed a stark revision, a morale-building boost, a makeover, a fresh articulation of national priorities, a shot in the arm to the American psyche that would lead to a propaganda windfall. Was he right? You tell me.

Mr. Brinkley argues that Kennedy’s “youth, radiance, vitality” — even his “poor health, philandering, the PT-109 incident” — but especially his “philosophy of courage” all coalesced to motivate him to believe that “bold steps forward are immortal.” He quotes the Beat Generation poet Allen Ginsberg: “Scientist alone is true poet he gives us the moon.”

From 1947 to 1957, Mr. Brinkley tells us, Kennedy’s friend and sometime alter ego was Wernher von Braun, whose “rocketry prowess and space technology genius were celebrated as national educational assets on TV” and on the covers of Time and Life. Despite his sinister Nazi past, reporters swooned over his charm, culture, movie-star looks, and his passionate commitment to going to the moon, which they considered “priceless national assets.”

His fan mail included mash notes from fawning women, teenagers wanting to know how to become rocket scientists, and even a note from a lady who wrote that “God doesn’t want man to leave the Earth.” She was willing to bet him $10 the U.S. would not make it. Von Braun replied that the Bible said nothing about space flight, but he said it was clearly against gambling.

Mr. Brinkley’s personal opinion is that “Wernher von Braun was culpable for war crimes associated with the German Third Reich, using slave labor to build his V-2s during World War II.” But while he should be honored for contributions to space exploration, “von Braun should not be treated as a sustainable twentieth-century American hero.”

There were plenty of naysayers and “conscientious objectors” to Apollo. Hans Thirring, a theoretical physicist, said that a manned moon voyage is like attaining perpetual motion, moving the Rocky Mountains, converting an animal into another species — “not an utter physical impossibility,” but it presented steep economic barriers. McGeorge Bundy, the national security adviser, thought the whole moonshot gambit was “grandstanding” and politically reckless. Others thought eradicating poverty was a priority.

Even though they were not close, J.F.K. had good (if not great) advice from Lyndon Baines Johnson: “The ‘multiplier’ of space research and development will augment our economic strength, our peaceful posture, our standard of living,” our educational system, and act as bold inspiration to young people. Even today, we can see the space program’s enduring ripples on 21st-century science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. To name just a few: voyaging to Mars, Tesla’s technologies, the detection of gravitational waves, and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence and planets beyond our solar system.

Presidential greatness (like genius) is the power to persuade. Eventually 20,000 companies and 400,000 individuals would contribute to Project Apollo. Maybe what drove Kennedy to gamble so much political capital was his tenacious competitive streak, his interest in space as the “New Ocean,” his Harvard education, his father’s legacy of win or die. Or his greatness.

He agreed with Einstein that imagination is more important than knowledge. He liked to quote Benjamin Franklin, who, after watching the first gas-filled balloon rise in Paris, was asked, “What good is it?” and said, “What good is a baby?”

Yet, sadly, Kennedy would confide to Ambassador John Kenneth Galbraith, “You will never know how much bad advice I had.”

Could such a bipartisan grand endeavor with so many moving parts ever happen again in the future? It would take more than charisma, chutzpah, and moxie — perhaps even more than an invasion of our planet by aliens — to marshal Congress, the private sector, and the American people to invest (or gamble) on a new New Frontier.

Mr. Brinkley’s well-researched book makes us realize why Cape Canaveral is now called Cape Kennedy, and why the NASA Civilian Launch Operations Center is called the John F. Kennedy Space Center.

Douglas Brinkley will sign copies of “American Moonshot” at the Authors Night benefit for the East Hampton Library on Aug. 10 in Amagansett and attend one of the dinners afterward.

Stephen Rosen, a physicist formerly at the Institut d’Astrophysique in Paris and at NASA’s Institute for Space Studies, lives in East Hampton and New York. He will give a talk titled “Albert Einstein: Rock Star” at the Cutchogue New Suffolk Library on Aug. 16 at 6 p.m.