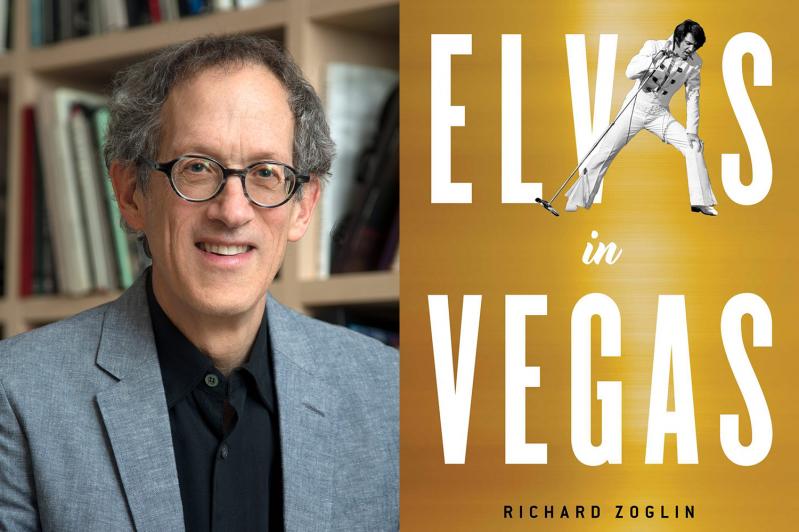

“Elvis in Vegas”

Richard Zoglin

Simon & Schuster, $28

You probably think you’ve had enough Elvis for one lifetime, yeah? I was 11 years old when the King called it a day, slumped over on his throne, chin on his chest with a fistful of Charmin that, sadly, would never see action. Since then there’s been an endless flow of biographies, made-for-TV movies, documentaries, docudramas, and feature films made about the Presley phenomenon — not a moment in the man’s life has gone unexamined, not a theory as to his musical, cultural, or social significance unexplored.

Now one would think that at some point (and that point should’ve been reached a long time ago) the King’s carcass would’ve been sufficiently picked clean and that it would stop — that there would be no demand for it anymore. I’m here to tell you that day is never coming and I’ll tell you why.

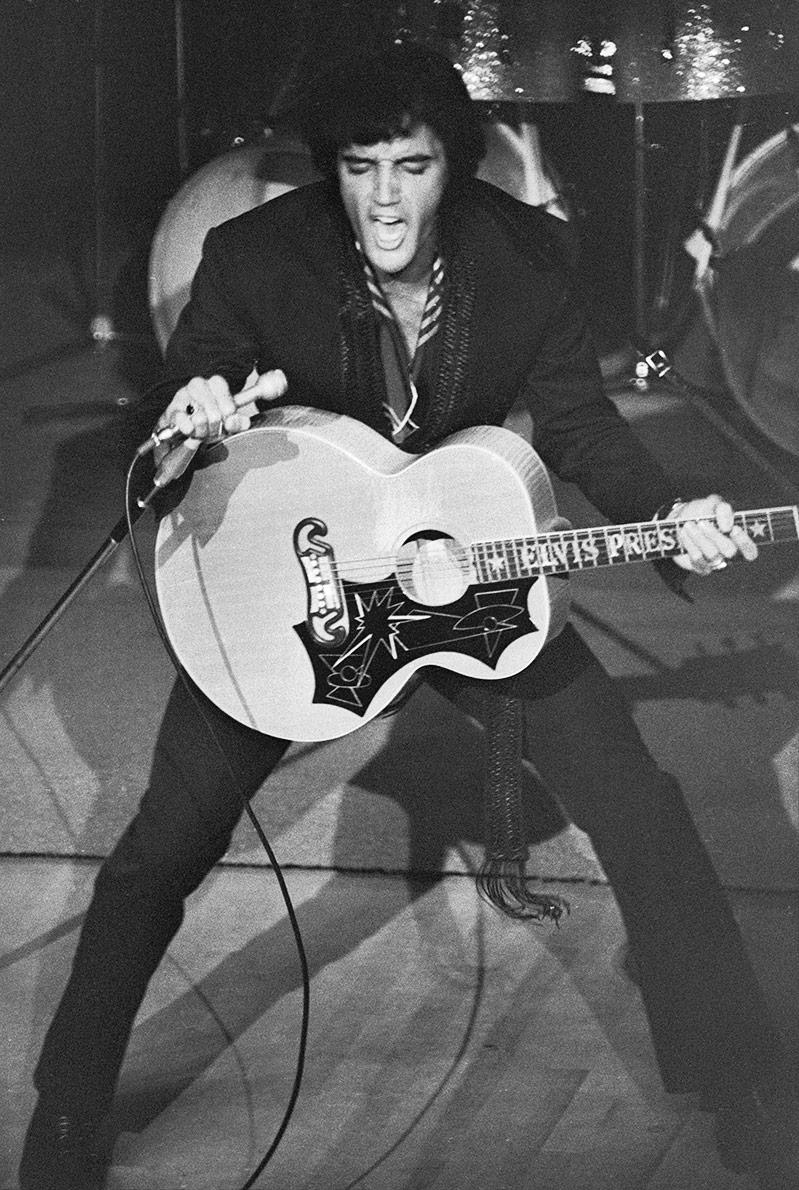

Let me ask you ask something: When you’re in an unbridled state of boredom and speeding through the channels, your light case of temporary A.D.D. run amok (this digital age has most certainly given us all a touch of it), and you come across an Elvis thing, maybe one of his early movies or a retrospective with concert clips and interviews, do you have to stop and watch it? You might leave it on for only a few minutes, but you’re momentarily spellbound by the sight of him and you stay with it for a while, right? I know I do.

I think that no matter how many times I see Elvis deliver a song, there’s still this disbelief that all of that beauty, talent, and combustible charisma could come together like that in one human being. We all have our favorites, but, to me, Elvis is uniquely ethereal that way. Watching him is stunning and surprising every time, as if it were my first time witnessing it.

We also love him because he did things like shoot his television set when he didn’t like what was on, and once flew with his cohorts from Memphis to Denver in the middle of the night on his private jet to get deep-fried peanut butter and jelly/bacon/mashed banana sandwiches. I came home hammered one night in my 20s and tried to make one. It didn’t end well. Here’s a tip: Don’t microwave the bacon.

So we’ll never tire of Elvis, and, musically speaking, or at least in a rock ’n’ roll sense, he represents the exponential leap from what was to what is; the evidence of that is still being seen today.

This point is well illustrated in Richard Zoglin’s new book, “Elvis in Vegas.” In it Mr. Zoglin chronicles Elvis’s return to live performing from the self-imposed gulag of his B-movie-making period, crescendoing with his much-ballyhooed comeback residency at the International Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip in July of 1969.

In addition to Elvis’s journey back to the stage, Mr. Zoglin gives us a well-researched historical overview of Vegas, from its rustic and small-time desert hospitality origins to its mob-masterminded growth and the ensuing golden age of the wild late-night lounge acts of the 1950s and early ’60s, profiling such musical groups as the Mary Kaye Trio and Louis Prima’s band featuring his wife, Keely Smith. He also explains the comedians’ role in the lounges and their importance as M.C. catalysts, unfurling micro-biographies of legendary comics — Don Rickles, Bob Newhart, and Buddy Hackett, who all built up their careers in Las Vegas.

Then (and I’ll ask for a drumroll, please) comes the expectant entrance of Sinatra’s “ring-a-ding-ding” era Rat Pack, who go on to rule the town for a number of years before the Beatles, Vietnam, and the counterculture change the country, and the tuxedo brand of cocksure crooning and booze-bag improvisation goes out of style (only to be cemented as classic a few decades later).

Right as the taillights on the Rat Pack vehicle figuratively begin to fade, who drives up but the always fun, Gandalf-the-wizard, Ginsu-knives-for-fingernails version of Howard Hughes, who takes up residence in Las Vegas and starts buying up the strip in a move of real-life Monopoly. He immediately ushers in a new order, pushing out the mob and corporatizing the casinos, and the happy days, as they once were, are soon over, leading to the eventual Disneyfication of Las Vegas that we see today.

In the book, we find out that Elvis had a career-long love affair with Las Vegas. He kept natural crackhead hours from the get-go, even before he started popping pills, and liked Vegas for the all-night action it provided (not the gambling, but the shows). So he spent a lot of time there even when he wasn’t working, but he actually got off to a shaky start there professionally.

His colorful carny manager, the infamous Colonel Tom Parker, as part of a quick money grab booked him for a two-week engagement at the New Frontier Hotel in 1956, the year of his meteoric rise, and he bombed miserably. The Vegas clientele of that time were all crusty middle-aged gamblers and wanted nothing to do with this new thing called “rock ’n’ roll.” Bewildered by his inability to turn it around, he sought the council of Liberace, who was already an established Vegas star and happened to be working there at the same time.

Liberace told him to dress up and go bigger with the show. Elvis wasn’t in a position financially then to employ that note and ended up handing the headlining duties over to his opener, the mercurial comedian Shecky Greene, but I think the advice was time-released. Fourteen years later he’d be gracing the stage in Las Vegas, a sequined and bejeweled white jumpsuit visage, spazzing out with karate kicks and engaging in overly dramatic and choreographed gestures. I never saw the connective tissue between Lee and the King before, but now it seems pretty obvious. I mean, it was right there.

I’m gonna come clean here. I’m a level-five geek when it comes to old show business stories. I can’t get enough of them, and this book is chock full of ’em — really interesting and cool ones, too. And what’s great is, in tandem with his copious research, Mr. Zoglin found great interview subjects, folks who are still around to tell the tale, including members of Elvis’s Las Vegas band, Corinne Entratter (ex-wife of the fabled Sands boss Jack Entratter), old showgirls who dated Elvis, comedians like the aforementioned Bob Newhart and Shecky Greene, and many others who give intimate accounts of their time there during the Rat Pack and Elvis reigns and lend credibility to certain stories and dismiss others as pure myth.

The one thing they all agree upon is that the enormity and spectacle of Elvis’s Vegas show in the ’70s, with the multitude of backup singers and 40-piece orchestra, shifted the paradigm and changed the Las Vegas show forever, and it never went back.

I don’t want you to get the wrong idea about “Elvis in Vegas” just because it’s a book about showbiz. It’s also very well written and informative as much as it is a good-time read. And you can tell Mr. Zoglin is extremely passionate about his two main subjects, Elvis and Vegas, and the meaning of their intersection — not in the sense that he’s overly rhapsodic or sentimental, but he delivers the story with great care, the same way Elvis and Sinatra did with a song.

Christopher John Campion, a singer-songwriter and regular visitor to Amagansett, is the author of “Escape From Bellevue: A Dive Bar Odyssey,” published by Penguin-Gotham.

Richard Zoglin lives part time in Wainscott.