What can we learn from the third iteration of Eric Firestone Gallery’s copious exhibition “Montauk Highway,” now on view in East Hampton? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Over the past few years, Mr. Firestone has turned his attention to rooting out the undiscovered or under-recognized artistic denizens of the East End. These artists have ended up in both solo and group exhibitions in his galleries here and in New York City. With hundreds of creative types finding their way out here from the postwar years to the present, not everyone could be or has been singled out in the way that their talent might otherwise merit. He is on a mission to rectify the imbalance by introducing lesser-known artists into a mix of their more enduring peers. And mix he does.

What is intriguing and exhilarating about these shows is that the unfamiliar and forgotten artists are placed right alongside some of the most esteemed artists of the 20th century to provide immediate context. Their placement reminds viewers that installations juxtaposing these artists were commonplace during the heyday of the New York School in galleries such as Tanager and Stable and the Whitney Museum’s annual exhibitions of contemporary art.

Featured on the center wall in the front gallery is a Pat Passlof abstraction from 1948. “Escalator” is a pivotal hybrid of European Cubism and a move away into a more imprecise interior realm adopted by the Surrealists. At this point in her career, she was studying with Willem de Kooning at Black Mountain College, where he became a mentor and influenced her work. Before learning that she later turned to figuration in depicting mythological creatures such as centaurs and nymphs, it was tempting to see the frenetic movements of such creatures in this work in a highly abstracted form. The chaos implied here is reminiscent of a 16th or 17th-century “Rape of the Sabine Women” subject by artists as such as Giambologna and Rubens, with the white rectangle a plausible plinth from which the old classical mode of expression was knocked down. It’s an endlessly fascinating painting, completely modern and yet steeped in history.

Nearby, a de Kooning oil-on-newspaper drawing, made in his studio by cleaning his brushes on that day’s New York Times, displays a date from 1969. It is a lively composition, seemingly random, yet full of the energy and color that marked his work from that time.

Speaking of de Koonings, a surprising Elaine de Kooning rounds out a figurative nook at the back of the gallery featuring the work of Jane Freilicher, Hedda Sterne, and Louise Nevelson. Her “Winter Still Life” is a lovely grouping of plants taken indoors from 1980. In her house in Northwest, she had a sunroom and a studio filled with light. It is easy to imagine these flowering plants happily soaking up the rays on a table there.

This grouping of women makes sense from the subject matter and their surprisingly figurative style. Elsewhere in the show, the female artists are blended into the rest of the room so that their achievements can be readily assimilated into the greater whole. As worthy as some recent exhibitions have been that have highlighted solely the work of women artists of this period, such shows can also be seen as continuing to separate women from the canon. What always has been revelatory about these “Montauk Highway” exhibitions is that the artists are displayed with little or no favoritism shown.

One fascinating case of a female painter making her way through the macho atmosphere of the New York School is that of Corinne Michelle West, who adopted the name Michael both professionally and privately. She is represented by a bright 1956 painting with a black linear skeleton called “La Voir (The Sight) After Juan Gris.” Sharing the wall with adjacent paintings by Manoucher Yektai and Joan Mitchell, the grouping demonstrates a strong use of dark linear elements in paintings otherwise filled with light or color.

Peter Busa, whose 1949 work is just down the wall from them, is much different in style. Inspired by Native American design, “Beauty and the Beast II” is considered one of his “Indian Space Paintings.” These works, which were hard to categorize at the time, do not look out of place with some of the other outliers in the room such as Joseph Glasco and Alfonso Ossorio.

Other artists who may be new to viewers include Michael Lekakis, Ernest Briggs, Fred Mitchell, Theodore Stamos, Paul Brach, and Sydney Geist. Each has on offer enticing examples of their work that merit further study. Stamos and Brach are probably the best known of the group. Stamos was a close friend and colleague of Mark Rothko’s, and Brach was married to Miriam Schapiro and also taught and served as dean at the California Institute of the Arts (Cal Arts) in Valencia.

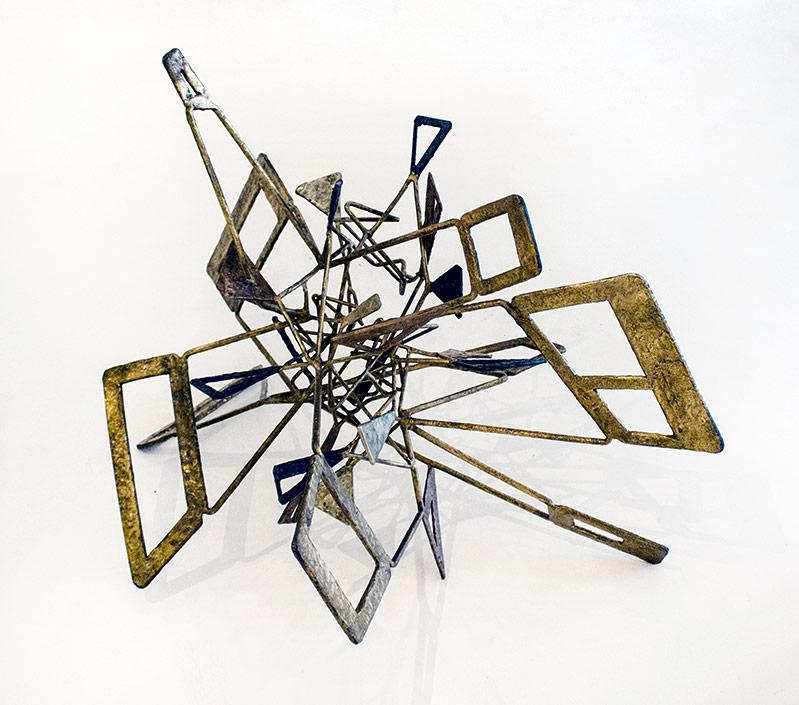

According to his New York Times obituary from 1987, Lekakis was gaining notice in his later years, after consistent showings early in his career at the Whitney. His wood sculpture “Spondilos” looks as if it were inspired by Grecian fluted columns from his ancestors’ homeland, but he has said his sense of form was influenced by the flowers his father arranged and sold through his business in New York City.

Fred Mitchell was one of the founders of Tanager. An artist cooperative gallery, it had other co-founders such as William King and Lois Dodd and members like Perle Fine (on view here in two impressive works), Alex Katz, and Philip Pearlstein. “Harbor,” from 1953, is indicative of Mitchell’s work at the time, using color in bold patches and black linear forms that allude to calligraphy and symbolism.

With more than 30 artists in the show, some will be old cherished friends and others quite mysterious, just as not everything will be to everyone’s taste. Yet there is likely something to please everyone, and others will be led on a quest of discovery.

The show is on view through Sept. 29.