In one photo, a couple is talking over a table of food, looking tired, but smiling at each other. In the next, a woman has her hand over her mouth, an expression of despair in her eyes, as she holds a sandwich above a cellophane wrapper.

On social media, Mark Smith has shared only a few of the pictures he’s taken of these ordinary moments at a refugee center in southeast Poland, just a couple of miles from the Ukraine border, yet there is something about them that serves to make the everyday consequences of the war in Ukraine very palpable for people an ocean away who can easily push it out of their thoughts.

“What’s happening in this country could happen anywhere in the world,” he said. “It’s important to keep it in the forefront of people’s minds.”

As many on the South Fork already know, Mr. Smith is not a photographer, but a restaurateur and partner in the Honest Man Restaurant Group, which owns Rowdy Hall, Nick and Toni’s, La Fondita, Coche Comedor, and Townline BBQ. He and his partners have often stepped up to help people in need closer to home, and as he watched the tragic news coming out of Ukraine, “I just intrinsically felt that I needed to do something,” he said on a phone call from Poland on Friday.

He has been volunteering for two weeks with World Central Kitchen, the chef Jose Andres’s not-for-profit that feeds people “in response to humanitarian, climate, and community crises,” according to its website. To help Ukrainians inside and outside the country, the organization has a kitchen and food supply depot in Poland and warehouses in Lviv, Ukraine, from which food is shipped to cities to the east including Odessa and Mykolaiv. It is supporting restaurants in Ukrainian cities still under attack and is expanding its operations to be able to feed people in five countries.

Mr. Smith is staying in Przemysl, Poland, where World Central Kitchen has set up a field kitchen that can turn out up to 100,000 meals a day. From there, food is delivered several times a day to the Hala Kijowska refugee center in the city of Korczowa. There, volunteers like Mr. Smith assure that fresh meals are available to refugees around the clock.

Assigned to distribution, he said the work is “sort of like running a restaurant.” In his nearly two weeks in Poland, he has tried to offer “the same hospital ity” to refugees passing through the center as he does to patrons visiting his South Fork eateries: service with a smile, a home-away-from-home welcome. “It’s not just about throwing food on a plate; it’s about connecting with people, serving them, trying to give them a momentary respite from their lives.”

“I don’t speak the language,” he said, “but that’s the great thing about feeding people. It’s universal. It’s a way of comforting people. I serve people in the literal sense.”

According to Unicef, since the war in Ukraine began on Feb. 24, “more than half of Ukraine’s estimated 7.5 million children have been displaced,” in an “outflux of people — mostly children and women” that “dwarfs all other refugee crises of recent years in terms of scale and speed.” And the United Nations Refugee Agency reports that between Feb. 24 and Monday, more than 4.6 million people had fled the violence in Ukraine, with more than 2.6 million of them arriving in Poland.

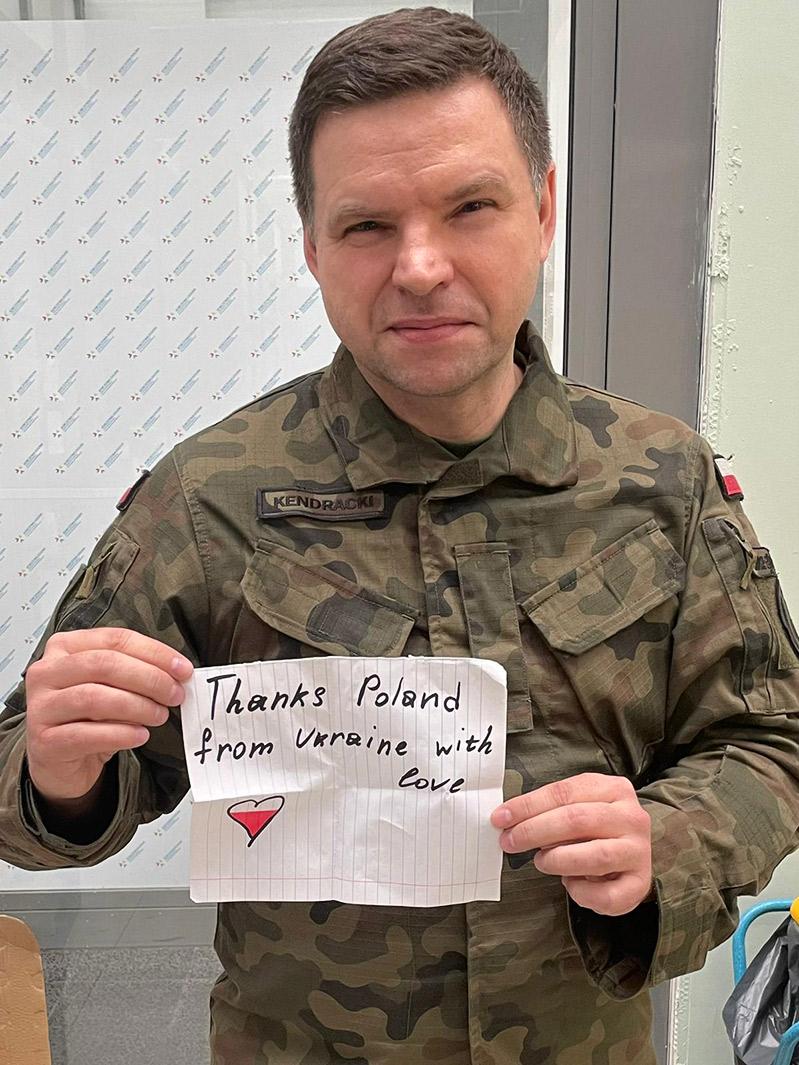

“The Polish people . . . are incredibly hospitable people,” said Mr. Smith.

He described the refugee center in Korczowa as a huge repurposed warehouse, possibly as large as half a million square feet. People coming from the Ukraine border arrive there by bus, some already knowing people who can take them in somewhere, and “they stay in the refugee center until that connection can be made,” Mr. Smith explained.

It recalls for him the situation in the Rockaways after Superstorm Sandy, where he and some of his Honest Man team delivered food in the days after the storm. Aside from this being a disaster wrought by man, not nature, the sheer scale of people in need is perhaps most striking. “There are just so many thousands.” He was prepared for seeing people sleeping on cots, rooms full of donations — of medical equipment, of boxes of food. “The masses of people are sort of mind-boggling.” Some people move on quickly, others he saw every day of his first week there.

“It’s intense, but it’s sort of uplifting in a way,” he said. In the worst of circumstances, “You also see the resiliency of people. Even in these situations, they’re fighting to keep their families together, literally and spiritually.”

“You can imagine the devastation, but you really can’t imagine the amount of giving,” he said of the many individuals and organizations large and small that are there to assist, “the people you meet, the volunteers from all over the world who stop what they’re doing and come and give of themselves.” There are psychologists, doctors, teachers, coaches. He met a troupe of clowns who drove all the way from Portugal and walk around the center just trying to make kids laugh.

The Ukrainian people “weren’t doing anything to Russia. And it’s hard for me to sit back and watch this when I feel I could be helping in any little way,” Mr. Smith said. The enormity of the crisis spurred him to action. “It’s easy to see the news and say, ‘That’s really horrible,’ and then forget about it until we see the news again.” He couldn’t get it out of his mind, and in fact found he was seeing blue and yellow, the colors of the Ukrainian flag, everywhere he went, almost like a message. He’s been posting photos of these Ukrainian reminders on his Instagram feed, as a small way “of keeping it out there.”

Not everyone moved to help can get on a flight to Poland, but there are many ways to be of assistance, he said. “People need to do whatever it is they can do,” he said. “Doing nothing is wrong; doing something is what it’s all about. Doing something is worthy.” If people have the means to donate, he said the World Central Kitchen, at wck.org, is a worthy cause, but there are “so many small organizations doing things to help.”