The Fast Track for Fresh Fish: The railroad changed the face of the seafood market, and the East End

The Fast Track for Fresh Fish: The railroad changed the face of the seafood market, and the East End

In 1895, 73 years after meat and vegetable merchants along South Street on the downtown Manhattan waterfront were officially recognized as the Fulton Market, the Long Island Rail Road was extended from Bridgehampton to Montauk, and that extra 10 miles of track would eventually become one of the foremost supply routes for fresh fish in the nation.

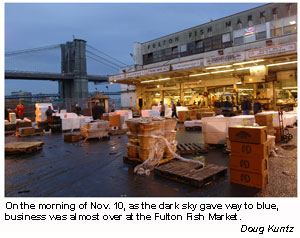

On Sunday, three tractor-trailer trucks, each carrying 35,000 pounds of loligo squid and whiting, left Montauk, heading for processors in New Jersey, and then to the new Fulton Fish Market, which opened for business in the Hunt's Point section of the South Bronx on Nov. 14.

Five more fish-filled trucks left for the city the next day. Montauk's Inlet Seafood alone ships an average of nine million pounds of fish to the Fulton Market each year. Refrigerated fish trucks also pick up boxes at the Montauk Fish Dock, from docks in Greenport, and at Shinnecock.

Years in the planning, and built at a cost of $85 million, the new Fulton market offers 400,000 square feet of refrigerated space to wholesale dealers who, in turn, sell to purveyors who distribute fish throughout the metropolitan area.

Despite the fact that Fulton's sources of supply have grown exponentially over the years, it is safe to say that the East End has made a major contribution to what is now the second largest fish market in the world. Only Tokyo's Tsukiji market is bigger. The impact of the Fulton Market on East Hampton and Southampton would be hard to overstate. The 100-mile run to the city and its gigantic appetite for fish freed fishermen from the need to market their catch directly. The city's diverse ethnic makeup has allowed fishermen to take advantage of the great variety of species that swim off the coast.

Gone is the darkly-lit world of South Street, with its ancient buildings and its strong odor of fish and of the 19th century. The law of supply and demand ruled there, one way or another, for 183 years. Also gone are the market's original links to the East End.

In 1879, Arthur Benson, the developer of Bensonhurst in Brooklyn, bought 10,000 acres in Montauk for $151,000. Ten years later, Mr. Benson and Austin Corbin, president of the Long Island Rail Road, became partners in a scheme to make Montauk a resort and deepwater port that would attract the well-heeled returning from Europe by steamship. After playing for a day or two, the posh set would return to the city by train.

The dream never materialized, however, in part because of Mr. Benson's death. In June 1895, Mr. Corbin bought 5,500 acres from Mr. Benson's heirs. The first train rolled into the Montauk station on Fort Pond Bay on Dec. 17, 1895. Mr. Corbin died the next year in a carriage accident.

During the summer of 1898, the dock was used by the Army to take soldiers off troop ships following the Cuban campaign of the Spanish-American War. Nearly 30,000 men recovered at Camp Wikoff, which, that summer, included most of Montauk. The pier extended far enough into the bay to accommodate up to three freight cars.

Whether or not the fish business played into Mr. Corbin's original plan, boats returning from the fishing grounds were now able to tie up at the dock and offload their catch directly into the waiting cars. After they were backed off the pier and coupled to the coal-powered steam engine, the train headed west. Montauk was not the only source of fish.

At 4 a.m. on Jan. 16, 1894, the American schooner Fanny Bartlett, loaded with 1,250 tons of coal, ran aground in thick fog. The railroad was under construction, and a flag station with a platform was built on Napeague. Someone removed a plank from the grounded schooner that bore her name and nailed it to the wooden platform. From then on, the Napeague flag station was known as the Fanny Bartlett stop.

According to Stuart Vorpahl, a commercial fisherman and one of East Hampton's three official historians, the platform was located beside the tracks where the remaining radio tower is today. Mr. Vorpahl said the platform was used by inshore fishermen who could have reached it either from Napeague Harbor or from the ocean side of the narrow stretch of sand that connects Amagansett to Montauk.

It was probably used by the Edwards brothers of Amagansett, who worked large, floating fish traps off the south shore of Napeague. The Edwardses also seined for menhaden, otherwise known as mossbunker, or bunker.

Beginning in 1872, a number of fish docks and processing plants were built at Promised Land on the north side of Napeague. There are three versions of how Promised Land got its name. According to the records of the East Hampton Town Trustees, the area took its name from the "large number of customers who promised to pay, but never did."

The roads were bad in the days when a sole deliveryman traveled them to carry supplies and the mail. The owner of the Smith Meal plant, the largest and longest running of the Promised Land businesses, was looking for an address. The letter carrier, a religious man, suggested Promised Land because it was so hard to get to.

Fannie Gardiner, a descendant of East Hampton's first English settler, once said she thought that an act of Congress had "promised" that the factories would never have to move because of their smell. The area was also known as Bunker Hill, because bunker were possessed there.

In any case, Mr. Vorpahl said he remembered the "oil cars" lined up on the railroad siding that connected the Smith Meal plant to the railroad's main tracks. The plant was closed in 1968. Neither the oil nor the fish meal were delivered to the Fulton Market, although market fish were also landed at the Promised Land docks, and presumably were sent by rail. Another platform for loading fish was located a bit farther west on Napeague near Mulford Lane, Mr. Vorpahl said.

The train made other stops for fish en route to the city. In November 1880, 3,000 barrels of crabs were shipped from the Moriches station. At Jamaica, the iced fish cars were directed to the railroad docks at the Bushwick Terminal in Brooklyn where they were loaded onto one or two-track barges, or "float bridges," as they were called. The barges carried the cars across the East River to the Fulton Market. After World War II, Long Island's roads had improved enough for trucks to take over the job of hauling fish. The railroad stopped its run to the Fulton Market.