After the Buffalo

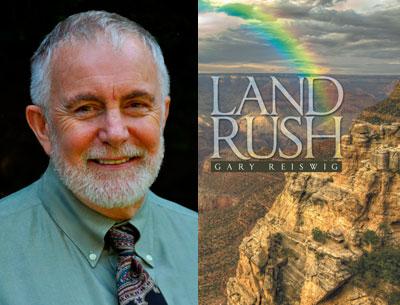

“Land Rush”

Gary Reiswig

Archway, $11.99

Gary Reiswig’s slim volume of four stories and two essays — one a memoir and the other family history — evokes the feel of growing up on a farm in the Oklahoma Panhandle during the middle part of the last century. The essays bracket the stories in “Land Rush,” and there is little tonal or thematic difference between them. All the pieces draw from the same familial well and the experience of farm and small-town life on the Great Plains.

The memoir and history provide a touchstone for the stories and reveal how much of his life Mr. Reiswig uses to infuse his stories with a sense of verisimilitude. As he writes in his brief preface, “These stories are based on true events,” of real things remembered.

The opening memoir, “The Buffalo Roam: And, Then, What Next?,” recounts Mr. Reiswig’s start in learning the “difficult but necessary farm lessons,” those having to do with hard work and the care and loss of animals. Those lessons expand into larger life lessons as well. At 12, he has reached the age where he is no longer only a son, but also someone who is expected to work the farm and carry his weight. When his beloved dog needs to be put down, Mr. Reiswig’s father asks him to do it.

“It wasn’t that Dad wanted to shirk the job. Rather, he wanted to cultivate my ability to discharge that kind of difficult but necessary responsibility.” Yet he is unable to bring himself to shoot the dog and remains uncomfortable when plowing the field near where the dog’s bones lie. Mr. Reiswig learns his father’s lessons even while knowing his temperament will take him in a different direction than the family farm.

The father-son dynamic introduced in “The Buffalo Roam” is a central focus in the stories as well. In “The Box Supper,” a box supper auction to raise money for a school is the scene of an unsettling competition between a boy’s father and Dootie Poor, a neighboring farmer. Dootie is “a small wiry man with a smirking grin” who makes too many comments regarding the boy’s mother and involves her in a suggestive practical joke. The mother dislikes him and calls him “a lot of names,” but her husband depends on his help: “He has new machinery. He’s the best farmer around here.” As far as the work on the farm is concerned, they are “lucky to have such a good neighbor.”

At the auction, Dootie tries to bribe the boy into revealing which box lunch his mother prepared. A tense bidding war develops between the husband and Dootie when both recognize the box lunch. The boy feels but does not fully understand the sexual tension underlying the bidding. While he is not completely cognizant of what is happening among the adults, “the boy felt the truth.”

“Two-Door Hardtop” slightly alters the father-son dynamic. Dean and his uncle Bernie have a close relationship. Bernie buys a new car a month before leaving to serve in the Korean War. He gives Dean the responsibility of taking care of the car in his absence, even though Dean is not yet old enough to drive. The car holds the promise of adventure and a life lived for both of them. Dean takes his responsibility seriously and anxiously awaits his uncle’s return.

However, Bernie returns from the trauma of war a different man: “He looked so empty, like he had left something from inside himself back in Korea. . . .” Dean cannot understand the change in his uncle and his lack of interest in the car. When Bernie sells it, Dean feels betrayed and longs for the time when he will own a car.

“Fair Game” is the book’s central piece of fiction. The story shares the same material as Mr. Reiswig’s 1993 novel, “Water Boy,” and focuses on the relationship between Danny, the young star quarterback for the Cimmaron Dustdevils, the high school football team, and his best friend, Sonny, the team’s water boy. Sonny, protected and influenced by his mother, does not play on the team, making him something less than the other boys who do in a town where football dominates community life.

Danny has a “God-given talent” and is a “once-in-a-lifetime kid.” Sonny, who offers game-winning suggestions to Danny and a coach on the sidelines, wants to be recognized for his own worth. Yet, in a community where football is tantamount to religion, is the best Sonny can achieve the reflected glory of being Danny’s best friend?

This is a multilayered story, and a good deal happens beneath its surface; Mr. Reiswig handles these undercurrents well. He suggests the forces that pull adolescents in different, and often conflicting, directions. Within a few pages questions concerning friendship, responsibility, death, deception, the place of football and religion within small-town America, as well as the idea of achieving the best years of one’s life far too soon are all presented.

“Bright Angel Trail” is a story of a family’s trip to the Grand Canyon at Christmastime. The trip echoes the one family vacation the father remembers taking as a boy, and it triggers complex memories for him regarding his relationship with his father and to what extent he may be repeating the same pattern with his son. The son, struggling to understand his own individuality, “felt small and uneasy about his place on the planet. What was his purpose?”

There is an intricate relationship among the mother, father, and child. They share an inability to communicate fully what they need, desire, and fear. Again, Mr. Reiswig only hints at much of this, allowing the reader to ponder the possibilities of the family dynamic and their future relationship.

The final piece in the book, “Free Land,” briefly traces the history of the establishment of the Reiswig family in the Oklahoma Panhandle. Mr. Reiswig’s ancestors moved from Germany to Russia in the 1700s to take advantage of free land to farm. The pattern is repeated in the next century when their descendants move from Russia to the United States to take advantage of the Homestead Act and settle on the high plains of the Panhandle. Mr. Reiswig provides a brief but vivid portrait of the harsh realities of trying to make a living farming on the plains, where the individual is at the mercy of the “landscape’s lack of generosity,” as he puts it elsewhere in the collection.

In his stories of young boys on the threshold of manhood, Mr. Reiswig portrays their dreams and desires, their uncertainties and fears — their longings to be recognized as mature and their, at times, foolish actions and subsequent feelings of guilt. They are acquiring an uneasy knowledge of the world’s realities and oddities, slowly coming to deal with loss, forgiveness, and understanding as they are initiated into experience.

Mr. Reiswig is not an effusive writer. He knows when not to say something, relying on subtlety and suggestion rather than an intrusive authorial voice. He has a plain and simple approach that emphasizes the commonplace and the past. All of these pieces have an easy, clear-eyed, conversational style — as if one were sitting around the kitchen table with a cup of coffee listening to Mr. Reiswig reminisce and tell his stories. It is not a bad way to spend an hour or two.

William Roberson taught literature at Southampton College for 30 years. He now works at LIU Post.

Gary Reiswig lives in Springs. A celebration of the release of “Land Rush” will take place at Ashawagh Hall in that hamlet on Dec. 19 from 5:30 to 7 p.m. There will be food and wine, and Mr. Reiswig will discuss the book at 6.