After the Flood

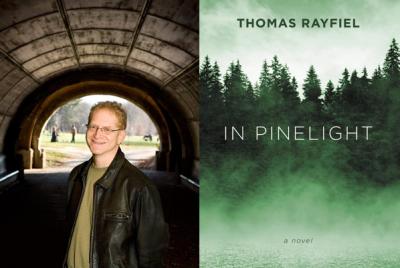

“In Pinelight”

Thomas Rayfiel

TriQuarterly, $18.95

“In Pinelight,” the sixth novel by Thomas Rayfiel, is narrated by an old, crotchety man living in a home for seniors. The novel is essentially a continuous reminiscing monologue. There is an interrogator who remains nameless and faceless throughout. We never hear his voice. What we do hear is the narrator responding to, or repeating, the interrogator’s questions.

“That’s the sound of shoveling. Cecil he takes his job seriously. Well, to see us through to the other side I guess. Other side of what? I never thought of this as a side.”

The tone of the book is that of an old man, rambling, recollecting, philosophizing, and chewing over the significant moments of his life and those of the people around him. In support of that tone, there is very little in the way of punctuation other than infrequent periods and question marks. No commas, absolutely no paragraphing, and lots and lots of run-on sentences.

The old man has lived most of his apparently long life in and around Conklingville, a small town in upstate New York that at some point was depopulated and intentionally flooded by the state in order to create a dam. I looked this up online, and the dam was built in 1930. This leaves him pondering what things are like deep below the surface of the water, an excellent metaphor for his attitude about everything he encounters.

“The funny thing is now I see it every day town through the waves. Yes Conklingville buried underneath the waves although you can’t really be buried in water can you? Drowned I suppose but no not drowned either because there was nothing left no one living so if it’s not living it can’t be drowned. Submerged I see it every day submerged.”

William had a rough start in life. When he was young his mother died, his older sister soon ran off with some stranger, and his father drank himself, if not exactly to death, then he drank himself into the front of the car that killed him. All of which left the young boy living alone and having to fend for himself. He made his living by becoming a carter, driving a delivery wagon behind two horses he loved, the willful and choleric Allure and the more placid Firebrand. To supplement his income he took on other odd jobs whenever he could — manual labor, as a night watchman for the local rich folks’ homes, and selling an elixir made of wild berries that he mixed with sugar and a liqueur of Benedictine and brandy.

“No I don’t have any more. That was a long time ago. Ray Eggleston he came by one day and told me they’d determined those berries the ones I was using along with the B&B that they were illegal. Imagine that. How could a berry be illegal? I asked. He didn’t really know or couldn’t really say but he also pointed out that I was selling liquor without a license plus it wasn’t really a medicine apparently the state says what is and isn’t a medicine too. The way he made it sound I was breaking about half the laws in the county a regular Al Capone . . .”

There is a sadness to his talk about his carting, as he was well aware that with the advent of motorized trucks, he was fast on his way to becoming obsolete. “A horse will take on any mood whatever you feel inside that’s what animals are for they show you what you’re feeling. Allure and Firebrand would go at a stately pace.”

“The milk truck doesn’t have anything to do with local history yes it took away my business but by then I didn’t mind it was all in bottles then the milk and they clinked so much that it drove me and Allure crazy and of course I didn’t have refrigeration . . .”

There is an intentional dreamy vagueness to the book. The narrator skips around in his storytelling from his present in the retirement home, to his long-ago youth (I am guessing perhaps in the 1920s?), and much of the time in between. We see him lose his virginity to Gabrielle for “a shiny dollar” in the local whorehouse. He gets married to Alice, the daughter of a local lawyer, and has a daughter. He drinks, often too much, and hides it from Alice and others.

“I wasn’t drinking not most of the time see I never got credit for all the times I wanted to drink but didn’t there’d be three or four times a day when I wanted to take a nip but didn’t but then if just once I gave in it’s not like that made the score four to one in my favor or anything like that.”

Specific dates are not mentioned, except that there are some scenes with the invading hippies that he informs us take place during the Summer of Love. For those of you who aren’t sure, that was 1967.

One of the places to which he made deliveries was a kind of odd and eerie and frightening clinic run by Christopher and Cochrane, two gay men. It seems a cross between a spa for rich people and a huckster medical clinic: “. . . they combined science and God. Cochrane he was the preacher of the group the snake oil salesman Christopher he was more the one who gave it its what would you call it its mystery.”

At one point the narrator spilled the contents of a box he was delivering to the clinic, and it was filled with eyeballs. Human eyeballs. He gathered them up again, and when he delivered the box he said nothing. Turns out they were injecting people with human body parts mixed up in a blender.

Mr. Rayfiel is clearly a talented writer, and parts of the book are entrancing, but I must admit to being irritated by what I saw as the unnecessary lack of punctuation and paragraphing, which not infrequently made me read, back up, and read again before I could grasp the meaning of a sentence.

“Everyone said how lucky he was and on the surface well he walked out of this hospital his wife Cheryl I remember Cheryl saying what a miracle it was but then it was like a different person had taken over his body or worse than that that the real him was somehow coming out in a way it hadn’t before like the leaves you know in the fall everyone says they turn colors but really that’s their true color coming out the chloroform that’s what makes them green no I know what I’m talking about I read it in Science magazine the chloroform it knocks unconscious the true color and then when it goes away in the fall everyone says Look at the colors but really they were there all along underneath.”

I will admit that after many years as a college English instructor, it is challenging for me to read this kind of nongrammatical writing without a mental red pen in mind. Still, there is much to enjoy and admire in “In Pinelight.” Like Sherwood Anderson’s “Winesburg, Ohio,” the book builds a picture, or more a collage, really, of a place and time that has disappeared. Small town upstate New York.

Michael Z. Jody, who regularly reviews books for The Star, is a psychoanalyst with practices in Amagansett and New York City.

Thomas Rayfiel’s previous novels include “Colony Girl” and, most recently, “Time Among the Dead.” He lives in Brooklyn and Amagansett.