Albert Einstein, Rock Star

A New York Times headline on Nov. 10, 1919, read: “Lights All Askew in the Heavens: Men of Science More or Less Agog Over Results of Eclipse Observations. Einstein Theory Triumphs: Stars Not Where They Seemed or Were Calculated to Be, but Nobody Need Worry.”

Albert Einstein turned universal gravitation into geometry. He converted space into space-time curvature. His equation of general relativity “rules the universe,” as the science reporter Dennis Overbye vividly put it, “describing space-time as a kind of sagging mattress where matter and energy, like a heavy sleeper, distort the geometry of the cosmos to produce the effect we call gravity, obliging light beams as well as marbles and falling apples to follow curved paths through space.”

Because Einstein had upended Isaac Newton’s theories and our homespun intuitions about space, he said: “To punish me for my contempt for authority, fate made me an authority myself.”

Bill Bryson quoted the best compliment: “As the creation of a single mind, it is undoubtedly the highest intellectual achievement of humanity.” I agree.

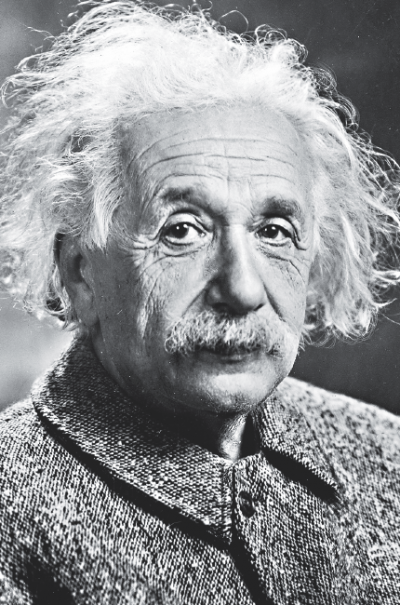

Einstein became not merely famous, but what we would today call a “rock star.” Everyone wanted a part of him. He was asked to speak at so many science conferences and ceremonial public occasions that he tired of fame. There’s a photo of him sticking his tongue out at the photographer.

A reporter encountering him on a train said, “Dr. Einstein, I’d like to interview you for my paper.” Einstein replied, “I’m not Dr. Einstein!” The reporter said, “But you are; I’ve seen your picture many times!” Einstein said, “Who should know better — you or me!”

Explaining General Relativity (1915)

How would you explain this to your parents, kids, or grandchildren? Here’s how I do it: Smartphones with global positioning systems use satellites, which need instantaneous corrections because their speed alters space-time (a la special relativity), as does the gravitational field of the earth (a la general relativity).

For your kids who inquire: “Space-time” has replaced our daily intuitive notions of space and time as separate entities. “Mass tells space-time how to curve, and space-time tells mass how to move.” Still puzzled? Einstein himself had trouble understanding all the nuances of his own theory, which others later improved on. When stumped, he once said, “I’m no Einstein!”

For grandchildren, I rewrote “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”:

Al/bert Ein/stein what a guy!

Had more thoughts than you and I

Spe/cial rel/a/tiv/it/y

Yeah yeah Em See squared is Eeeee.

Grav/i/ta/tion holds us down

It bends light a/round the town

It makes G/P/S/es right

Squee/zes space-time oh so tight!

Genius

There are two kinds of genius: one, the garden variety who’s just like your smartest friends and colleagues — only much smarter; the other kind’s abilities and profundities are so extravagantly beyond the first kind’s that their mysterious gifts seem to imply they came from another planet . . . like Einstein.

When he was only 5 years old, Einstein discovered a magnet and, mystified, later observed, “Something deeply hidden had to be behind things.” At 12, he was enchanted by plane geometry and its lucid methods of axioms and theorems. In 1905, he wrote three papers — each worthy of a Nobel in Physics.

A Dimple in Space-Time

General relativity is simpler to visualize by analogy. Imagine a rubber sheet stretched like a drum skin. Push down at the center, depressing and stretching the sheet (like putting your finger to your cheek creating a dimple). Now imagine many small BBs rolling along the dimpled drum skin toward the depression. Some of the BBs will strike the central depression and some will skirt it, curving around the depression as they follow the easiest path (called a “geodesic”).

The BBs resemble particles of light (photons). The depression resembles a dimple in the (four-dimensional) space-time continuum, like the one that surrounds a massive object: our sun. Its huge solar mass “warps” the surrounding four-dimensional space-time fabric enough to cause the BB or photon’s path to “bend” enough to be observed astronomically. Gravitational warping of space-time is enough to really bother a satellite, to cause galaxies to act as a lens, magnifying objects far beyond them, and to produce gravitational waves. Their detection is the next frontier for astronomers.

Special Relativity

More subtle and slippery to grasp, special relativity (1905) started when Einstein tried to define simultaneous events as seen from a moving train versus as seen from the station. Einstein knew the startling experimental result that the speed of light is constant no matter whether the light is coming or going from a moving or stationary source of light. He postulated there is no preferred absolute reference frame. Time has to slow, space has to shrink, and mass has to increase when viewing a moving train from the platform, or when viewing the platform from a moving train. This is why Einstein (a great wit) asked a train conductor, “Does Oxford stop at this train?”

Einstein’s Long Hair

My mentor, Banesh Hoffmann, has his name on a scientific paper with Einstein and spoke about their work together in the 1930s at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J.

Sitting side-by-side in Einstein’s office, they were baffled by a problem in the complex equations of general relativity. To contemplate a solution, Einstein got up and paced the floor while twisting his famously long hair (now fashionable), muttering, “I vill a little think.” After a few moments, he sat down with a good solution.

After Einstein died in 1955, Banesh told me that whenever he got stuck on the same equations, he would get up from his desk, pace the floor, twist his hair, and think. “But,” he said, “it never worked.”

Dr. Stephen Rosen, a physicist who lives part time in East Hampton, is the author of a memoir, “Youth, Middle-Age, and You-Look-Great!” He will discuss “Einstein’s Jewish Science” on Dec. 20 at 1 p.m. at Temple Adas Israel in Sag Harbor.