Among the Monster People

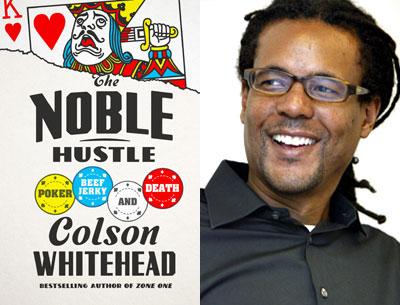

“The Noble Hustle”

Colson Whitehead

Doubleday, $24.95

Those searching for the latest how-to book on Texas hold ’em or a straightforward account of the World Series of Poker in Colson Whitehead’s new memoir, “The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky, and Death,” are in for a surprise. It isn’t written by the latest guru or moonlighting celebrity. The author will not be cluing us in on stratagem or mind-blowing philosophies. This is a tale told by an outsider, a creature of metaphor and simile set upon a unique subculture. He’ll report to the mother ship in his own distinct tongue, and we are welcome to observe.

This is indeed a memoir about the World Series of Poker, yet be forewarned. Any college dropout who heads to Vegas with this book in tow will find himself trapped inside a vortex of his own doing.

With a suicidal monarch on the cover and a bone-chilling first line, Mr. Whitehead’s journey begins. “I have a good poker face,” he says, “because I am half dead inside.” This is a statement we might expect from a no-name gunslinger riding into town, or perhaps something less than human. Zombies are big now. So is poker. Mr. Whitehead offers both.

In an essay for The New Yorker in 2012, Mr. Whitehead made an assertion regarding his life’s work that lends a great deal of insight to this book. “An artist is a monster that thinks it is human,” he wrote. We learn that, as a child, the best-selling author of “Zone One” preferred to stay at home absorbing an array of bad cinema until he came upon a genre called psychotronic, a hurried, low-budget style of horror-science fiction that mesmerized him.

“They were unaware of their utter freakishness,” he explained, “unaware that the world found them absurd. . . . If these movies existed then surely whatever measly story was bubbling in my brain was not so preposterous.”

This breakthrough offered the young writer total freedom to develop a style of unique observation and lightning-quick prose packed with boundless pop culture references. When admitting a desire to establish a King Kong persona at the poker table, he confesses, “On the Simian Scale, I was more Bubbles the chimp, break-dancing for cigarette and gin money before Michael Jackson rescued him from the streets.” The author is just getting started, fine-tuning an engine of revved-up witticisms and one-liners.

Mr. Whitehead freely admits to being no poker expert. He is a better-than-average player who enjoys a friendly game with writer friends. When a magazine editor offers to bankroll him the $10,000 entry fee for the World Series of Poker, he accepts. There will be no payment for his account of the experience. His payment is the entry fee.

He decides upon Atlantic City, “Vegas’s little cousin,” as an excellent training ground for the big competition and goes searching for his people, the monsters and unrepentant losers who inspire him, before he even arrives. Unfortunately, New York’s Port Authority has cleaned up a bit, offering little to none of its former infamy. “I could be anywhere,” he laments, “starting a journey to anyplace, a new life or a funeral.” He climbs aboard a state-of-the-art Greyhound and ponders his chances as “one of the most unqualified players in the history of the Big Game.”

Mr. Whitehead’s mind really starts to twitch once he arrives at the Tropicana Casino and Resort. “The contemporary casino is a more than a gambling destination; it’s a multifarious pleasure enclosure intended to satisfy every member of the family unit.” Despite intense makeovers to the culture and atmosphere of legalized gambling, Mr. Whitehead knows that diehards never change. “I found my degradation,” he marvels. “I was among gamblers.”

Here is where we find the author’s monsters, something akin to Kerouac’s “mad ones.” They’re the ones who’ve stopped pretending, a people of oblivious purity. They live life as they see fit, so incredibly uncool that it somehow makes them wondrous.

Mr. Whitehead approaches the table and sums up the competition as though he were describing a legion of superheroes: “Big Mitch is a potbellied endomorph in fabric-softened khaki shorts and polo shirt. . . .”

“Methy Mike, a harrowed man who had been tested in untold skirmishes, of which the poker table was only one.”

“And then there was Robotron, wedged in there, lean and wiry . . . a young man with sunglasses and earbuds, his hoodie cinched tight around his face. . . .”

He joins them representing his own tribe, a dystopia he inhabits called Anhedonia (the inability to experience pleasure). “We Anhedonians have adapted to long periods between good news. . . . We have no national bird. All the birds are dead.”

By the time he’s ready for the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas, Mr. Whitehead’s hired a personal coach to administer crash courses, pep talks, and numerous conference texts. The man is taking this seriously and becomes enthralled with the unlikely desert oasis. “I recognized myself here. Monster places for monster people.”

Due to Mr. Whitehead’s unique powers of observation and assessment, the reader considers the possibilities should he step away from the table to wander the cartoonish landscape. What would he think of tourists clutching two-liter margaritas or men snapping escort cards on every corner? With this writer the possibilities are limitless. But this is a memoir about poker.

The author eventually learns staying power at the table, a core value he compares to writing. “In novel-writing, biding is everything. . . . Waiting years for a scofflaw eleven-word sentence to shape up into an upstanding ten-word sentence: This is the essence of Patience.”

In time we discover the role that beef jerky plays in all this, and the influence corporate sponsors have on Mr. Whitehead’s adventure. His odyssey concludes with an ending that film buffs may recognize from past decades. “But you know how ’70s sports movies end.”

J.B. McGeever is a graduate of Stony Brook Southampton’s M.F.A. program in creative writing. He is at work on a novel about the closing of a New York City high school.

Colson Whitehead is the author of “Sag Harbor,” a 2009 book based on his experiences growing up there. “The Noble Hustle” comes out on Tuesday.