Appetite for Beauty

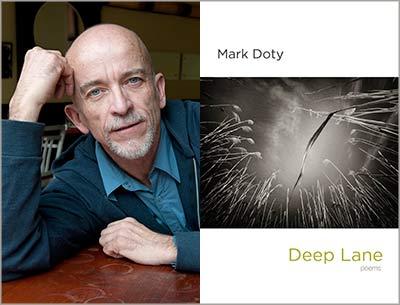

“Deep Lane”

Mark Doty

W.W. Norton, $25.95

Mark Doty’s “Deep Lane” is a book about country, symbolized by gardens and animals, frequently Mr. Doty’s dog, Ned, who accompanies him on long walks, but also birds, deer, goats, sea lions, a mammoth, a white fish, and ticks that enter his Eden. “Deep Lane” is about city in poems that take place on New York’s streets, in bars, gyms, hospitals, and barbershops.

In each of these environments, the poet’s appetite for life and awareness of loss and recovery are omnipresent, particularly when human beings make entrances: the poet’s ex, his present love, his mother and father, painters like Robert Harms and Jackson Pollock, and poets, among them Alan Dugan and Robinson Jeffers.

Poetry, a leitmotif throughout the book, beautifully captures Mr. Doty’s deep connection to his identity as a poet. He shows us, with a touch of irony, Alan Dugan, the “recalcitrant old boho,” and with precise description, Robinson Jeffers, a poet who “who could not be wholeheartedly pleased / with anything human.” His awareness of the art of poetry extends his humanity, as in the poem “ARS POETICA 14th St. Gym,” in which the title equates the precepts of poetry with “beauty that does not disguise the wound” when a one-armed man lifts himself on a pull-up machine.

Another major human connection, of children with their parents, was painful for Mr. Doty. He reveals this honestly as they speak to him from the underworld in poems that evoke their hurtful relationship with him. In “Apparition,” as he trims forsythia at the kitchen sink, his father says, “Mark is making the house pretty.” We learn his father did not speak to him for the last five years of his life, but he concludes that though he has been addressed in the third person, “He did say my name,” and it wasn’t mockery.

His mother, gone for 30 years, similarly is given the benefit of the doubt when her voice in him says, “You’ve got to forgive me,” and for a moment they are at last “equally in love / with intoxication,” after which she says, “I never meant to harm you.” The understatement in these poems is masterful in conveying irony and hurt.

But pain caused by humans can be mitigated by the beauty of nature, as in “Verge,” a poem about blooming cherry trees on the highway in April, which turns into a love poem when the poet, after a party, walks with his soon-to-become lover to his motorcycle, “perhaps a pair / of — could it be — soon-to-flower trees?” Mr. Doty shows his appetite for beauty and for life most clearly in “Hungry Ghost,” where he learns from his teachers that “my desire was a thirst / for something beyond forms.” He wonders, “When I’m gone, will I stop wanting?” He concludes that wanting “is also a form of immortality.”

The poem that to me most fully and poignantly represents the theme of loss and recovery is “This Is Your Home Now,” an elegy in which he describes the closing of the barbershop on 18th Street where the Peruvian barbers for years have been comforting: “I was happy in any chair, though I liked best / the touch of the oldest, who’d rest his hand / against my neck in the thoughtless confident way.” When the shop closes and he feels at a loss, he finds a sign, WILLIE’S BARBERSHOP, down the street. Willie tells him, “This is your home now,” leading Mr. Doty to the recollection of “the men I have outlived” and for whom he still feels grief.

The barbershop metamorphoses into “the kingdom of the lost” as Mr. Doty adds up his present satisfactions, a man who loves him, their dogs, more years together. For those of us who have lost a sense of belonging, this poem strikes a universal nerve.

In other poems home represents life’s difficulties. An example is “Spent,” when the poet, locked out of his house several times as he tries to bring the hydrangeas he cut inside, has to climb through a window, reminding us, almost comically, of life’s unforeseen hazards. And yet, as he shows in the poem that follows, “Amagansett Cherry,” “the contorted thrust” of the cherry tree, rather than an unbent branch, is what gives it fervor.

Eight of the poems in “Deep Lane” are titled “Deep Lane,” the site of the poet’s Eden with its “crooked house” that exemplifies his human Garden of Eden. This shingled house symbolizes a oneness with nature. This is where the poet picks radishes, walks through paths in a cemetery, pulls up wild mustard.

The city, on the other hand, is a place of more human experience, as exemplified in “Underworld,” “the boy in outpatient . . . has failed to kill himself,” and in a needle-drug addict in “Crystal.”

“Deep Lane” sometimes seems more emotionally invested in the plant and animal world than in the human, most fully in “The King of Fire Island,” where “a buck in velvet at the garden rim” observing the men in “tea-dance light” makes the men “objects of his regal, / mild regard,” rather than he, theirs. The deer becomes “monarch of holly” and “hobbling prince of shadblow grove,” while “the men swayed and danced.”

When a deer’s head is found floating in the bay, the poem resolves its narrative by the poet asking to be guided out of the story and concludes the deer “must have been weary of that form, / as I grow weary of my head.”

What is so compelling in this long narrative is how the buck ultimately takes over the poem, and the island’s men who “stand with cocktails” recede as mere mortals.

Mr. Doty’s projection of himself as one with the deer epitomizes his constant identification with animals and plants, both an escape and a recognition of the mortality of humans. “Deep Lane” is a book of such moments; a paean to the fertility and the tragedy of human, animal, and vegetable life. It is sensitively and subtly written, and deeply satisfying, as the power of love with a found mate merges with the beauty of the natural world.

Carole Stone’s most recent book is “Hurt, the Shadow: The Josephine Hopper Poems.” A professor emerita of English at Montclair State University, she lives part time in Springs.

Mark Doty of Springs won a National Book Award for “Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems.” He teaches at Rutgers University.