Art in Embassies: The Nation’s Best Face

The Capitol dome that greets visitors emerging from Union Station is a jarring welcome to Washington, D.C. Constructed to be a reassuring monument to probity and permanence, it now stands for the nation’s crippling divisions, personified by the voting members of the United States Congress. Seeing it in the flesh, unmediated by pixels or screens, it is a palpable and potent talisman of dysfunction.

How transformative, then, to be whisked away to the U.S. State Department to a reception and dinner where government and private endeavor join to put the nation’s best face forward as we greet the world, the implied din of competing viewpoints quelled by those working for a greater good.

That is the history and present function of the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies, an organization that works hand in hand with the State Department to provide art to America’s diplomatic buildings around the world. It is the kind of world where liberal Hollywood, in the guise of Meryl Streep, can participate in a celebration of Alice Walton, a Walmart heiress, purely for her efforts to promote American art in an atmosphere devoid of the divisive dialogue that is Fox News and MSNBC’s bread and butter.

A small but varied sampling of the type of work the foundation has secured for the government through donations and commissions for this mission is now on view at Guild Hall. It includes artwork by Ellsworth Kelly, Vija Celmins, Chuck Close, John Baldessari, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Susan Rothenberg, and many others. Robert Storr, the man who put the show together, is the dean of the Yale School of Art, a former curator at the Museum of Modern Art, and the chairman of the organization’s professional fine arts committee.

It is a sober task and one that he and the artists who work with the foundation treat with great seriousness. Some have criticized the committee’s choices as tame, but Mr. Storr disagrees. In a telephone conversation last week, he said that the artists who participate understand the gravity required. “No artist has chafed at any restrictions that might have arisen from the diplomatic mission,” he said. “It just hasn’t come up as an issue.”

Since all the committee members are busy professionals within the field of visual arts, much of their discussion about new acquisitions is done over the phone. This can be as simple as one work, often original prints in a limited edition just for FAPE or, lately, photographs, or more complex site-specific works commissioned for different places. Artists like Lynda Benglis, Maya Lin, Ellsworth Kelly, Joel Shapiro, and Sol Lewitt have had such artworks installed in embassies in India, China, Germany, and Turkey.

A good portion of the art serves a public relations purpose and is put on view in the main floors accessible to visitors, but Mr. Storr said much of it is in private offices as well. “Embassy workers spend hours and hours there writing up policy statements or processing passports,” he explained. “We want to give them something that engages their mind when they look up.”

He hopes, for example, that someone’s initial wariness of abstract art might shift to engagement and pride of possession. For that to happen, “it has to be intrinsically interesting.”

Although Mr. Storr has had the luxury through MoMA and other venues of having his pick of the best art and exhibition spaces, the work he does for FAPE is challenging in other ways. He is limited by the art that already exists or comes into the collection and the space available to display it, be it hallways or office walls.

“Yes, it’s a challenge,” he acknowledged, “but it can be done, and I have done it a lot. It’s like solving a puzzle step by step.”

At the beginning of his career, he said, he worked with a large corporate art collection. “I was a hammer-and-nails guy, hanging paintings above the desk. I know from way back how to solve those problems.”

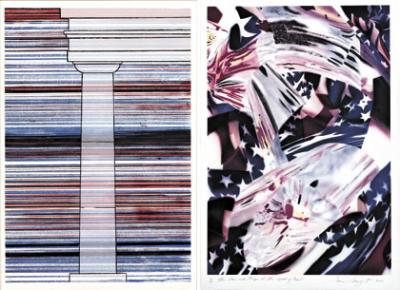

Artists who agree to design print editions specifically for FAPE may look to the history and symbols of the nation as an inspiration. Flags are common images, as are color abstractions featuring red, white, and blue. A recent Carrie Mae Weems donation is a self-portrait in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

Just as often, symbolism that might be read into works was never the artist’s intent. “If someone is determined to see symbolism, you can’t stop them,” said Mr. Storr, but neither FAPE nor the artists, nor the diplomatic missions and embassies themselves, put forward ideological readings.

Mr. Storr will moderate a panel discussion with Tina Barney, Ms. Benglis, and Mr. Shapiro on Saturday from 3 to 4 p.m. at Guild Hall on the role of the artist working with his organization. One of the central questions will be how to make artwork independent of politics. Most artists, he said, are “keen to do just that. They are not trying to do nationalistic art. They want to represent the best we can offer in visual culture.”

The show will be on view through July 27. A reception will be held after the panel discussion from 4 to 6 p.m.