Ask Him All Questions, Tell Him No Lies

Unlike the rest of us, when asked for advice Philip Galanes doesn’t have to wonder if it’s flattering or if an honest response would touch the third rail of social intercourse. As the “Social Q’s” columnist for The New York Times, it’s his job, and he’ll take on all supplicants and entertain all embarrassments.

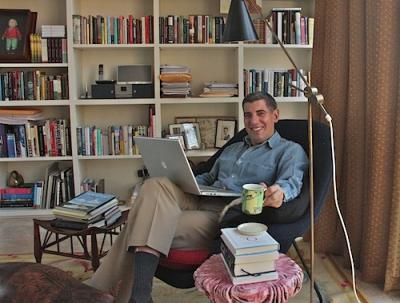

Beyond the professional veneer, the hell of other people is further mitigated because he writes, largely, from the comfort of his East Hampton home.

“The column lets me be out here a lot,” he said the other day. “The best way to sort out other people’s problems is by walking a dog on the beach.”

Writing an advice column isn’t work you apply for. An editor of the Sunday Styles section turned out to be “one of the 17 people” who bought Mr. Galanes’s 2004 novel, “Father’s Day.”

“She said, ‘This is the voice I want.’ Smart-alecky but with a heart behind it. It’s nice that it came out of what I thought was the biggest failure ever.”

That editor, by the way, “transferred out to another section. That seems to be how it works at The Times — you never leave the building, you just move to a different desk.”

“Starting out, the column was clearly entertainment, with a little bit of service. But I quickly saw that people needed help. When it’s your problem, common sense goes out the window. People get hamstrung by their own annoyance.”

“We receive several hundred questions a week,” he said, “and it doubles from November to January.” (That was no royal “we” — the volume alone has cost him “more than one assistant.”) “We’re all so spread out from our families,” managing them at a distance. “At the holidays we come together, and it creates a massive amount of stress.”

“We see people and it makes us nervous. E-mail and Twitter keep people at an arm’s length. The digital revolution took away a lot of stuff; we’ve lost a muscle when it comes to dealing with people face to face.”

Mr. Galanes’s experience with face time comes in part from his work as an entertainment lawyer. He said he has a dozen or so clients in the fine arts and theater. “The column is a silent process, and it can be lonely,” whereas in his practice, “clients always have problems and want to talk.”

“I do,” he said when asked if he thought an expertise in etiquette related to lawyering, its minding of Ps and Qs, as it were, its, uh, empathy? “I try to imagine what the lawyer on the other side would say. . . . The job is to bring people together and see how to make things work. When you say you’re totally wrong or totally right, it never works.”

“Hold your hollandaise, Benjy!” Mr. Galanes wrote to Ben from Florida, who earlier this month asked him about the wisdom of proposing marriage in front of his girlfriend’s parents at a big family brunch. “I took a sensible approach,” in effect splitting the difference: Why not proceed with the proposal without a parental surprise that could ruin their first party of the new year?

“The guy 100 percent disregarded my advice.” (Mr. Galanes wondered if such an impulse to self-display resulted from too much reality TV.)

He called on his lawyerly diplomacy regarding a far touchier subject when a Latina with a fair-complected white husband wrote in to relay how, say, on an elevator she would be mistaken for her child’s maid or nanny. His advice? Extend a hand and introduce yourself.

“People were furious. They wanted her to shout, ‘You racist!’ But it was an honest mistake. We all make assumptions. . . . Why make it a war?”

“The sad questions I get are the ones I feel really need help, more than the Styles section can give them.” When kids write him, for instance.

“This one girl, 13 or 14, was told by her boyfriend that if she drank balsamic vinaigrette she wouldn’t get pregnant. And she writes me? Something’s going wrong here. We like to assume kids are so sophisticated today, but they’re still kids, not fully developed.”

“Besides, everybody knows it’s ranch dressing.”

The success of the column led to a book of the same name, out from Simon and Schuster not long ago and subtitled “How to Survive the Quirks, Quandaries, and Quagmires of Today.”

“After publishing novels” — “Emma’s Table,” a comedy of manners, appropriately enough, was his most recent — “and nonfiction, it’s been like a walk in the park. . . . The book keeps going and going. People really want to talk about stuff we don’t deal with day to day.”

One recent question broached the subject of payment for private tutoring when the matter hadn’t been brought up beforehand. Mr. Galanes elucidated the faux pas: “But what if you were thinking $500 an hour, and Miss Mortarboard’s parents were leaning toward a thank-you lunch at the Olive Garden?” That column went online a couple of days ahead of its Sunday publication and within hours of its posting he’d “already received 40 letters on either side of the issue.”

“It may be a sad thing to say about the world, but yes, it’s one of the most popular parts of the paper. Take that, Maureen Dowd.”