From the Beckett File

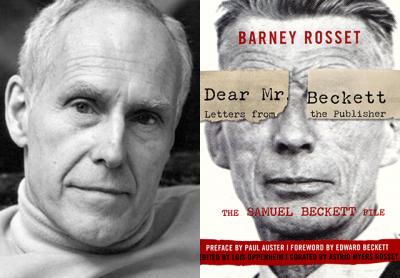

“Dear Mr. Beckett”

Barney Rosset

Opus, $32.95

”Barney and I go to the tennis matches. . . . We play games, and we talk politics. We don’t talk literature. I don’t talk literature with nobody.” — Samuel Beckett

Years ago Barney Rosset’s wife, Astrid, telephoned to invite me to shoot pool with Barney in their East Hampton home. Me? Pool? I told Astrid I’d think about it and call her back.

I pondered the fact that I hadn’t played pool since I was a kid and I was no good at it then. Next I thought about Barney, the legend. And I got the quivers. Who was I to play pool badly with a legend? I called back and declined.

The legend? Rosset died in 2012, age 89. The New York Times front-page obit chronicled his life. And what a life.

Rosset, the son of a Chicago banker, was a lifelong renegade. His one credit was a 1948 film he produced, a documentary called “Strange Victory,” about racism in post-World War II America — a noble flop. His previous publishing hit was a mimeographed newspaper, The Anti-Everything. But that adolescent effort predicted a future that would change America and indeed world culture.

One of Rosset’s first acquisitions for Grove Press, a modest reprint press he acquired in 1951 for $3,000, was with an unknown writer named Samuel Beckett, an Irishman who lived in France, wrote in French, and was rejected by French publishers. An initial letter to Beckett, included in “Dear Mr. Beckett,” a marvelous collection of interviews, telegrams, reviews, clippings, canceled checks, book covers, contracts, letters, photos, and scribbles, goes as follows: “Our catalogues have already been mailed to you so you can see what kind of a publisher you have latched onto . . . I hope you won’t be too disappointed. We will do what we can to make your work known in this country.”

Beckett responded in June 1953: “I hope you realize what you are letting yourself in for,” going on to explain that his novels were unsalable, his plays unperformable, and adding, “All are difficult in ways which I am not disposed to mitigate.”

After this unpromising start, Beckett and Rosset first met in Paris at the bar of the Pont Royal Hotel. Rosset recalls: “Beckett came in, tall, trench-coated and taciturn . . . ready to get rid of us.” They ended up near dawn drinking champagne at La Coupole.

And so began one of the great literary and personal friendships of the 20th century. Rosset’s first letters to Beckett from New York begin with “Dear Mr. Beckett” (June 15, 1953), progressed to “Dear Samuel” years later, and finally, on March 23, 1957, “Dear Sam.” It is not too much to say that Rosset truly loved Beckett — even naming his son Beckett. This just doesn’t happen in today’s conglomerate culture. Love is bad for the bottom line.

Beginning with “Waiting for Godot,” which revolutionized world theater, Rosset was to publish almost all of Beckett’s work. Beckett went on to win a Nobel Prize in 1969. He was not pleased with the froth of his prize, but accepted it anyway.

Rosset’s other publishing triumphs included the works of Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco, Frank O’Hara, LeRoi Jones, David Mamet, John Rechy, and Marguerite Duras.

His legal campaigns against the censorship of D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer” were epic. United States censorship rules at the time were rooted in the 19th century. The government dictated what we could and could not read. To bring a banned book into the country was the equivalent of drug smuggling. Rosset, in a one-man war, changed all that. He fought more than 60 legal challenges for Miller’s book alone (which he had signed up over a game of table tennis with Miller). It sold 100,000 copies in hardcover and over a million in paperback.

Rosset loved a good legal fight and eventually had the funds for those fights. He was our great postwar cultural impresario. As the filmmaker D.A. Pennebaker said, “He knew what would last and what was dross. I think he was born knowing. Very few are. . . .”

Lois Oppenheim in her introduction to this wonderful literary scrapbook notes that what Beckett and Rosset “had in common was perseverance. ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on. . . .’ ”

Even after Rosset overreached and ended up with fancy offices, 120 employees, and mounting debts and was bought out by George Weidenfeld and Ann Getty in 1985, he kept on going with new presses named Blue Moon and Foxrock. Despite lifelong accusations of being a “smut peddler,” he ended up a true cultural hero.

No review can do justice to this comprehensive and detailed compilation about Beckett and Rosset and so much else. A big thank-you to Astrid for pulling this all together, presenting facsimile reproductions that, as one reviewer put it, exude “a wonderful period aroma.” “Dear Mr. Beckett” is an essential document of a revolutionary era in American letters and culture. He was our scrappy, daring, and unbowed neighbor.

I am sorry I didn’t go to play pool with him. In fact I never even met Barney. This is my eternal regret.

Bill Henderson is the publisher of the Pushcart Press in Springs.