Behind the Big Bat

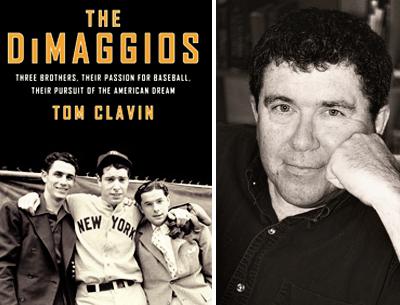

“The DiMaggios”

Tom Clavin

Ecco, $25.99

When I told my wife I was reviewing a book titled “The DiMaggios,” she asked me, “There was more than one?” There were, in fact, three — the brothers Joe, Dom, and Vince, all big-league ballplayers of varying skill levels and fame.

But it’s the subtitle, “Three Brothers, Their Passion for Baseball, Their Pursuit of the American Dream,” that’s the problem, identifying the book as a document in the long literary history of this country’s animating vision, of which baseball, of course, played a part. The DiMaggio parents, Italian immigrants who worked hard to give their children a better life in San Francisco than they could have had in Sicily, had a version of the American Dream in their minds that corresponded to the classic narrative that has shaped the fiction of Horatio Alger, Nathanael West, John Updike, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Arthur Miller.

The problem is that none of these three brothers was Jay Gatsby (though perhaps Vince, who ended up selling Fuller brushes door to door, was a kind of Willy Loman). Dom, the one with the brains, always underrated and in Joe’s shadow as a ballplayer though he was voted American League M.V.P. in 1947, at least found a successful career in business. And Joe, after Marilyn Monroe’s death, became even more reclusive, bitter, and paranoid than he had always been. None of them was a hero, least of all Joe, who just wanted “an excuse to get away from the house.”

The fact that Joe was lionized by the press and the fans was the product of America’s conflation of athletic skills and character. Undoubtedly, the cult that surrounded him was enormous: Paul Simon’s lyric “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio? / A nation turns its lonely eyes to you” testifies both to the size of the myth and to the absence of the man, and Joe reveled in his fame, using it as a screen to keep everyone else out. He was from the start vain, not very bright, suspicious to the point of paranoia — a loner who seldom spoke to his teammates and ended up estranged from both brothers.

Here’s what he told Gay Talese in 1966: “There are . . . personal things that I refuse to talk about. And even if you asked my brothers, they would be unable to tell you about them because they do not know.” Clavin quotes Charlie Silvera, a Yankee teammate, as saying that Dom and Joe “each in his own way was a great guy and a great ballplayer.” But Clavin makes it abundantly clear that Joe was anything but a great guy. Vince was the affable one; Joe was, as Gay Talese put it, “a kind of male Garbo.”

Telling the story of these three lives involved, for Clavin, a prodigious amount of research; he seems to have read every book, every article, every news story written by, for, and about the brothers, their family, and about baseball itself in the ’30s and ’40s — he stops just short of including box scores. And this is a problem: He doesn’t really tell a story. “The DiMaggios” is something of a cut-and-paste job, an immense amount of data arranged in chronological order, but with no overarching idea to serve (not those in the subtitle, at any rate). Too much space is taken up by meaningless factoids (a friend of Joe’s, serving in Korea, was promoted to sergeant; Ted Williams had fun learning how to fly; Lefty O’Doul died on “the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor”).

And it isn’t only facts that Clavin’s research turns up, but opinions as well: Whenever things get pulled together in a meaningful way, it’s Roger Kahn or David Halberstam who’s doing the pulling. Clavin seems to have interviewed several members of the DiMaggio family and scene, but the only one he quotes extensively is Vince’s daughter, Joanne DiMaggio Weber. And she’s good for an anecdote every few pages. But as a family member, she’s not necessarily a reliable witness (though I believe her when she says that her favorite baby sitter was Phil Rizzuto). The “as told to” autobiographies produced by each of the brothers are, as Clavin rightly calls them, formulaic, self-serving, and unreliable.

But there have been many biographies of Joe, one of the best being Richard Ben Cramer’s “Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life,” an excellent and juicy book that probes into all the sordid, interesting crannies of “the hero’s” stunted personality. Where Clavin tells us that after his divorce Joe “wasn’t looking for another wife, just companionship,” Cramer reveals that between and after his marriages, virtually the only women he met were prostitutes, one of whom still marvels at Joltin’ Joe’s physical attributes: He was “bigger than Milton Berle,” she said, Uncle Miltie representing the phallic paradigm of the ’40s and ’50s.

This is juicy stuff, and it’s what’s missing from Clavin’s version. It’s not that “The DiMaggios” is sanitized, just that it’s plodding and literal, lacking narrative style and telling details. The brothers’ personality quirks are mentioned regularly but Vince’s affability, Dom’s shyness, and Joe’s sullen grudge-holding get lost among endless reiterations of what happened in Cleveland, in New York, in Boston on summer afternoons 70 years ago, when Joe went 3-for-4 and won a game that won a pennant that led to yet another World Series. In 1950, “The gutty Red Sox did not fold. On July 18, their 12-9 win over the Tigers at Fenway Park brought them to .500 at 39-39. In the next 59 games they went 47-12.” There must be baseball fanatics who will lap up all these stats and replays, but for most of us, a little more than a little of that is much too much.

When the book gets interesting, predictably, is when Joe meets Marilyn. Clavin observes that they slept together on their first date, though I think it would be bigger news if they hadn’t; “dating” doesn’t seem like what these two were up to. Yet Clavin, in defiance of all evidence that their marriage was a liaison between two damaged, narcissistic, sex-addicted celebrities, tells us that their wedding was “a fairy-tale event for gossip lovers,” attended by none of Joe’s family. The marriage lasted less than a year.

“He had loved her deeply. He always would,” writes Clavin. But Joe really was incapable of love, and didn’t want a homemaker and child-rearer for a wife; he’d tried that once before and gotten burned. Neither had any idea who the other really was. Returning from a promotional tour of Japan, Marilyn told her husband, by now retired, “You never heard such cheering.” He replied, “Yes, I have.” The people closest to him probably shared Toots Shor’s opinion of her: “Joe, what can you expect when you marry a whore?”

The last few chapters of “The DiMaggios” are painful, as the brothers’ relationship deteriorates and one after another they sicken and die. Joe seems in his later years to have fallen under the spell of a sleazy lawyer named Morris Engelberg who made his money on the memorabilia circuit impersonating, as it were, Joe DiMaggio, and who, as Joe lay on his deathbed, may have pulled his World Series ring off his finger and then tried to pull the plug on his ventilator.

The kid who just wanted to get out of the house ended up hoarding money and, except for a moocher, alone. If this is the American Dream, it’s a sad one.

Richard Horwich, professor emeritus of English at Brooklyn College, writes regularly for this and other publications. He lives part time in East Hampton.

Tom Clavin lives in Sag Harbor.