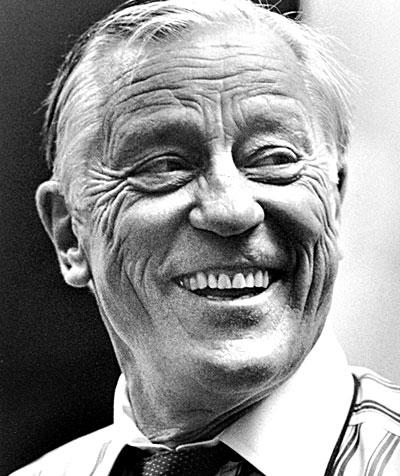

Ben Bradlee, Newspaperman

If Ben Bradlee was the archetypal American newspaper editor — brash, gravelly voiced, profane, barrel-chested — he also happened to preside over his paper, The Washington Post, during a golden age of journalism, 1968 to 1991, when reporters’ work never mattered more.

At its height, it was a time of spread collars and crushed cigarettes, of Dictaphones and shoe leather propped up on desks. It was before the profession diminished in the face of daily, even hourly, pressures to deliver superficial tweets, before online copy was made cumbersome by the interruptions of digital advertising and even, briefly, by “buy now” links embedded in stories, following the Amazon mogul Jeff Bezos’s 2013 purchase of The Post for a relatively bargain-basement $250 million.

“Oh, Ben has said publicly that he was there at the right time,” Ken Auletta, who writes about the media for The New Yorker, said yesterday. “It was easier for him then. He was editor at a time of expansion, when The Post became a national paper. And then to see the layoffs and the bureau closings, it was depressing for a guy like that.”

Mr. Bradlee, who led The Post through its biggest stories and tumultuous times, from the 1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers, the secret history of the military’s involvement in Vietnam, to the following year’s coverage of the Watergate cover-up, which brought down the Nixon administration, died at home in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 21. He was 93.

“He was an amazingly charismatic guy,” John Leo, a columnist for U.S. News and World Report for nearly 20 years, said. “When he walked into a room, he was the center of attention, for men and women alike.”

Mr. Leo and Mr. Auletta, part-time Bridgehamptoners, had socialized several times each summer with Mr. Bradlee, who with his third wife, the writer Sally Quinn, bought Grey Gardens on Lily Pond Lane in East Hampton in 1979.

Mr. Bradlee and Ms. Quinn, a former style section reporter at The Post, gutted and renovated the house, which might be the village’s most famous property, known as the falling-down residence of Big and Little Edie Beale, relatives of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis who became quasi-celebrities after a 1975 documentary by Albert and David Maysles aired their eccentricities.

In his book “A Good Life” Mr. Bradlee wrote that, 15 years on, he could still smell the urine of the Beales’ army of cats every time it rained.

“Ben was the kind of guy men would talk about the same way women would: ‘Isn’t he sexy?’ ” Mr. Auletta said. “But he didn’t talk about himself — you know, war stories, Watergate. You had to draw him out. It was one part modesty and one part security, and that’s what made him attractive.”

“He was an upbeat character,” Mr. Leo said, “and he always listened to people, which isn’t always the case with the famous. The Brahmin part didn’t hurt either,” he said of Mr. Bradlee’s patrician Boston background and Harvard education. He was born in that city on Aug. 26, 1921, to Frederick Josiah Bradlee Jr. and Josephine de Gersdorff Bradlee.

“You got the sense he would have gone far in whatever he did,” Mr. Leo said. “He had that kind of psychic pull on people.”

As it was, after two years’ service aboard a destroyer in the Pacific during World War II, Mr. Bradlee worked briefly at The Washington Post before accepting a position in 1951 as a press officer at the American Embassy in Paris. Three years later he joined Newsweek magazine as a European correspondent. By 1965, he was back at The Post as managing editor and, three years after that, executive editor.

“Ben, Sally, and Quinn [their son] would come up from Washington every August,” Mr. Auletta said. “Ben, Sally, and I would often go to a movie. He just loved movies; he’d cry like a baby — even at action films. Then we’d get a beer and a burger at Rowdy Hall.”

“At Grey Gardens he’d play tennis, swim in the pool. He enjoyed just sitting around talking about journalism, world affairs. . . .”

And then there was the garden. “What do we need it for?” he said at the first meeting with its designer, Victoria Fensterer. Ms. Quinn had hired her after seeing the work she had done for a friend, the screenwriter Nora Ephron. The Bradlee gruffness soon gave way to “How did we ever live without it?” Ms. Fensterer said, and then to an enthusiastic, “I’m the first in my family to have a real garden.” Ms. Fensterer tended it for 24 years.

“What a pleasure it was to be around him,” she said. “He always seemed happy and connected to you in the moment.”

“The funeral last week in Washington was a tribute to Sally too,” Mr. Auletta said. “She really made his life better. I have a daughter the same age as Quinn, and Sally and my wife were pregnant at the same time. I remember we spent New Year’s together” in the early 1980s, “and Ben was very expansive that night. He talked about Kennedy,” whom he had known at Harvard and befriended in Washington, “and about being a godparent to John-John. Jackie was not happy with his book on J.F.K.” — “Conversations With Kennedy” — “because it said he used ‘florid language.’ Meaning he cursed.”

Capping a newspaper career that included 18 Pulitzers on his watch, in 2013 President Obama awarded Mr. Bradlee the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the country’s highest civilian honor.