Between Devotion and Betrayal

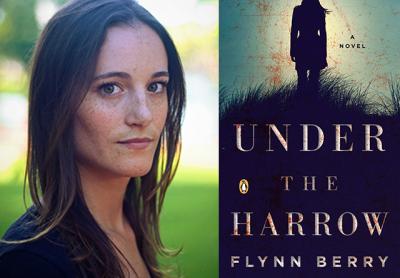

“Under the Harrow”

Flynn Berry

Penguin Books, $16

A thriller is supposed to thrill and this one does, right from the outset, but not with the usual car chases or shootouts or spooky, otherworldly phenomena. Instead, the reader is gripped by masterful plotting, tight, elegant prose, and assured psychological insight.

Nora Lawrence, the narrator of “Under the Harrow,” has come by train from London to the small, bucolic suburb of Marlow to stay with her sister, Rachel, a visit she happily anticipates. The 30-something siblings, survivors of haphazard parenting, are especially close. Their conversations are intimate and sympathetic; they’ve rented a vacation house together in the past and plan to do so soon again. Nora, who’s recovering from a painful breakup, is looking forward to sharing some good news — she’s been awarded a residency at an artists’ retreat in France — and a celebratory drink.

She’s not alarmed when Rachel isn’t at the station to greet her, and she sets out by foot to Rachel’s house. The bloody scene she encounters there is shocking — her sister dead of multiple stab wounds, and Fenno, Rachel’s large German shepherd, hanged from a banister and turning slowly on the noose of his lead. The details are certainly grisly, but not gratuitous. Nora’s shock is also ours, her grief palpably real, coming down “like a guillotine when the woman put her finger to Rachel’s neck.”

At the police station, she thinks, “It’s strange to be so tired, and also so scared, as if my body is asleep but receiving electric jolts.” And much later, she wants to tell someone “about the moment between opening the door of the house and understanding what had happened, when what I felt was wonder. It was an incredible feeling, golden and drugged. . . . I wouldn’t mind living my whole life in that gap.”

We learn that Rachel, a nurse, had endured another brutal physical attack — years earlier, when she was a teenager — for which no one was ever charged. Nora sustains guilt about that event because she chose to sleep in rather than accompany Rachel on the day it happened.

Gradually and steadily, we become aware of other details of the sisters’ past and of their character. Rachel harbored obsessive vengeful thoughts about her first attacker, owned a blackjack, and had committed lesser acts of violence herself, like dropping beer bottles on a bartender’s feet and punching a man in the head at a party. When a detective remarks that Rachel could be unpleasant, Nora evokes a smile by saying, “I liked that about her.” Nora, who has a history of sleepwalking, keeps a carving knife under her bed and carries a straight razor and pepper spray by day.

Despite Nora’s conviction that she and Rachel kept nothing from each other, she discovers that Rachel withheld some vital information. Her beloved dog, Fenno, was acquired as much for protection as for companionship. She had recently stayed for a week with her best friend, lying about a broken boiler at her own house. But even when Nora unearths a disturbing personal betrayal — a valid reason for ambivalence — she’s still irrevocably devoted to Rachel: “Bitch, I think, and the venom does nothing to how much I miss her.” And she’s no less determined to find her sister’s killer.

Several suspects present themselves, with Nora, not surprisingly, among them. Others include Stephen Bailey, the man Rachel almost married — “Close brush, she said” — and Keith Denton, a married plumber who seems to be fixated on her. He admits to having seen her on the morning of her final day. And Rachel had mentioned meeting with someone named Martin — from work, she said vaguely, but no one at the hospital can place him.

Then there’s Andrew Healy, Lee Barton, and Paul Wheeler. All of them have served time for inflicting grievous bodily harm on women. Rachel seemed to think Healy was her initial assailant. She had even visited him recently in prison, another secret she’d kept from Nora. The lead detective asks questions about the sisters’ father, an alcoholic and a petty criminal with whom they’ve lost touch. The detective wants to know if he’s violent, and Nora isn’t sure.

Is there any connection between Rachel’s murder and a woman from the sisters’ hometown who’s gone missing, or with a local, fatal car crash? Rachel knew the accident victim. Nora is convinced that her sister was being stalked; she shows the police a place in the woods with a clear view of Rachel’s house, a virtual hideout littered with beer cans and cigarettes. She pictures creepy Keith Denton as the voyeur, but the police suggest she might have set the site up herself.

“Under the Harrow” is written in the present tense, so that everything seems to be happening in the very moment it appears on the page, heightening its cinematic suspense. The novel offers many pleasures in addition to its driving narrative, especially the fresh and scrupulous descriptions of place and circumstance. At Rachel’s funeral, Nora observes, “The air in the church is restive and tortured, the result of two hundred people trying not to make a sound. I wish they would all talk.” She feels isolated in her mourning, but when the last of the guests leave, she “thought they would stay longer, and knowing that they didn’t is like watching it grow dark in the afternoon.”

After an impulsive hookup with a man she met at a bar, she says, “He was handsome and the encounter was surreal, and jolly, as they can be sometimes, as though we had a snow day when everybody else had to work.” And when the detective with whom Nora becomes involved asks her what she hates about London, she tells him it’s the noise. “The noise is the best part,” he says, which really resonated with this big-city-loving reader.

Best of all, though, are Nora’s thoughts about her sister — “Her face is so familiar it is like looking at myself” — whom she resurrects in moments of wishful amnesia before lapsing again into the horror of reality, where loneliness, as she puts it, has her by the throat. She thinks, “I don’t know how to survive the hours until I can sleep.”

But her misery is nothing compared to Rachel’s forfeiture of the living world, of the extraordinary and the mundane. “She had so much left to do . . . she has been taken away from everything, she lost everything. She likes red lipstick, and will never again stand in the aisle at a chemist’s, testing the shades on the back of her hand.”

Flynn Berry, an American writer, has chosen a British setting for her story, perhaps in homage to Ruth Rendell and P.D James, both virtuosos of character study, whose literary heir she might be. There’s never a sense of dislocation or fictional tourism in “Under the Harrow.” It’s a classic whodunit that is greatly enriched by the quality of the writing. I found myself marking up pages while fighting the urge to turn them.

Even the book’s title seems inspired. Its source, revealed in the epigraph, is “A Grief Observed” by C.S. Lewis, an aching meditation on the death of his young wife. “Come, what do we gain by evasions? We are under the harrow and can’t escape.” Love and loss, and their fateful link, are also at the heart of this debut novel by a first-rate storyteller.

Hilma Wolitzer’s novels include “An Available Man” and “The Doctor’s Daughter.” She lives in New York City and spent many years in Springs.

Flynn Berry has spent summers in Amagansett since 1990.