Beyond the Cinderblock

“A World Unto Itself”

Ruth Ann Bramson,

Geoffrey K. Fleming,

and Amy Kasuga Folk

Southold Historical Society, $40

It is refreshing that in this age of communication indecision our cousin fork is turning out an impressive number of regional studies that trace architecture, visual arts, and local lore within the confines of paper covers. Not unlike the revival of vinyl records, books seem to keep dodging death.

There is little question that the Southold Historical Society has taken the lead in supporting local history publications with a delightfully eclectic lot of well-illustrated volumes shedding light on many aspects of North Fork history that deserve attention from a much larger audience. Rather than returning to print older writings, the society has focused on bringing us new authors and exciting new research. While I await a full history, written by an academic, of any one of our townships, I am mighty happy to get my history fix through shots rather than a cocktail.

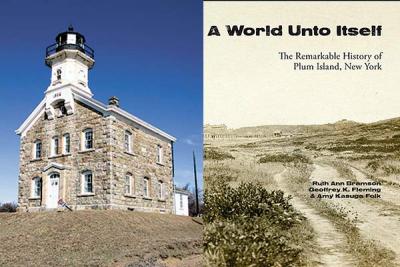

One of the most recent publications from the Southold Historical Society is “A World Unto Itself: The Remarkable History of Plum Island, New York” by Ruth Ann Bramson, Geoffrey K. Fleming, and Amy Kasuga Folk. The “Remarkable” in the title may be hyperbole, but the story of Plum Island is fascinating.

Most of us have met the island only from afar, as we ferry past it on our way to and from New England. It seems oddly close to us as we peer out the ship’s windows at the island’s famous lighthouse. This picture-postcard image is almost a state of Maine cliché. There cannot be anything amiss in such a lobster roll setting, right?

Well, if we look back at what the beach read of 1997 was, you might think differently. Nelson DeMille’s best-selling novel “Plum Island,” with its bad-boy detective, murder, and genetically altered viruses, certainly induced me to look deeper into the windswept landscape of the island for a glimpse of those sinister cinderblock labs filled with Frankensteinian experiments. Later titles for the Plum Island bookshelf have been “Lab 257: The Disturbing Story of the Government’s Secret Plum Island Germ Laboratory” by Michael Christopher Carroll, an exposé of the island’s biological warfare research, and, most recently, “Plum Island” by Michael Williams. Mostly the island gets the Fox News approach to journalism.

Thankfully, Ms. Bramson, Mr. Fleming, and Ms. Folk treat their subject with respect, facts, and a taste for storytelling.

One of Long Island’s early historians, Nathaniel Prime, wrote in 1845 that “Plum Island contains at present about 800 acres, and is inhabited by only three families, including fifteen individuals . . . the surface of the Island is very stony, and has no wood except a small pine swamp.” This is not an inviting description, but the authors have uncovered reams of new primary-source material that introduce the reader to a very detailed and engaging journey. They start us off with prehistory and the geological formation of the island and continue up to last year’s election ousting Representative Tim Bishop, who was active in trying to decide the island’s fate. As history never stops, so goes the story of Plum Island.

Adriaen Block’s 1635 map was the first to delineate Plum Island. Tradition tells us that wild beach plums once grew there in large patches, hence the island’s name. To the Native Americans, it was called Manittuwond, or “the island to which we go to plant corn.” Its transfer from Mammawetough, sachem of the Corchaugs, to various colonial governments and individuals is clouded. By 1648, several representatives of the New Haven Colony purchased lands that included Plum Island. In 1659, Samuel Willis, a Connecticut magistrate, made a deed for the island with the sachem Wyandanch, facilitated by Lion Gardiner on Gardiner’s Island.

The Town of Southold claimed the island’s ownership in 1665. To clarify the matter, the governor of the New York Colony, Edmond Andros, granted Willis a patent that made the island a manor in 1675. The governor, the year next, gave Southold Town the right of civil jurisdiction, but the manor was still owned by Willis. Willis sold Plum Island after 10 years. Just about 1700, the island was divided by two buyers, Samuel Beebe Jr. and Isaac Schellinger.

The story of the island continued as a progression of farmers raising cattle, sheep, and hogs. Players like the Gardiners of Rhode Island and the Tuthill and Truman families all had their roles to play. Chapters on significant events like the American Revolution and the War of 1812 enrich this portrait of the island by reminding the reader of the local importance that national and international situations presented, even to an area that might have seemed remote.

After the Civil War, Plum Island real estate began to beckon those big-city investors who are always looking for the next gold mine, oil well, or resort property. Through inheritance and purchase, several islanders had increased their land holdings, and by 1883 the entire western end of the island had been purchased anonymously. It turned out to be a partnership named the Plum Island Company, led by Abram Hewitt, a former mayor of New York City. His representative was Edwin Bedell, a New Jersey merchant who worked out of New York City. Through some clever foreclosures, Hewitt had rid himself of his other investors and most of Plum Island was ready for groundbreaking by 1889. But, oddly, Hewitt did not start a resort; rather he continued to lease farmland for grazing.

The United States declared war on Spain in 1898, but the government had started acquiring land the year before for the construction of Fort Terry on Plum Island. The first purchase was for 150 acres (it later turned out to be 193) for $25,000. In 1901 an additional 647 acres was bought for $64,700. The government owned the island.

There are many chapters — on rum-running, shipwrecks, the lighthouse, the history of Fort Terry, the Maj. Benjamin M. Koehler court-martial case (involving the sexual harassment of over a dozen of the men in his command), and the transformation of the island into an Animal Disease Center.

This book is richly illustrated with period photographs, engravings, and works of art. The three authors have created a seamless narrative that speaks in one voice.

This is definitely a book for historians, but because of the wealth of the material and the fact that the narrative is confined to one small island, it can certainly be read for pleasure. And since we don’t know yet what might happen to Plum Island in the next few years (will it be sold, will it be given to Southold, or whatever), this book is history at its most current. It is also about the only way you’ll get to see what is on the island without being arrested!

Richard Barons is the executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society. He lives in Springs.

Geoffrey K. Fleming is the director of the Southold Historical Society, where Amy Kasuga Folk is collections manager. Ruth Ann Bramson is a historian who lives in East Marion.