The Big Man, by Jeffrey Sussman

He was big: 6 feet 4 inches, 260 pounds, and all muscle. He had hands that seemed as large as catcher’s mitts. His large, rectangular face and broad features reminded me of one of the heads on Easter Island. He played football in the 1930s for John Adams High School in Queens. One day, he beat up three pro-Nazi members of the German-American Bund, which supported Hitler in the 1930s. For that heroic act he was briefly known as the Knight of Woodhaven Boulevard.

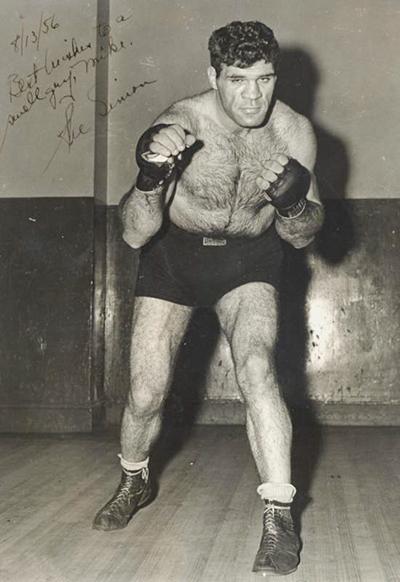

His name was Abe Simon. He was a friend of my father and my uncle Harold. He became a heavyweight boxing contender.

I met him three times. While I found his appearance intimidating, he was really a gentle giant, soft-spoken and quick to smile. I was surprised that one who looked so hard and tough was a lover of classical music and always had a radio tuned to WQXR, New York’s classical music station. He was such an odd mixture of tough and tender that The New Yorker published a profile of him in April 1941. He lived on 215th Street in Bayside, Queens, with his wife, daughter, and son, and worked as a liquor salesman.

By the 1950s, when I met Abe, he was suffering from severe arthritis that made walking painful. Back in the 1930s, however, he seemed indestructible.

My father told me that Abe, while playing football in high school, broke the leg of a running back on an opposing team. Some boxing promoters sitting in the stands had watched and admired the big, hulking football player and thought he could be molded into a heavyweight boxer. They offered him a lot of money and said they would arrange for him to be trained by one of boxing’s legendary trainers, Freddie Brown.

In addition to being a great trainer, Freddie was also considered one of the best cut men in the sport. Among some of the more famous boxers he worked with were Rocky Graziano, Rocky Marciano, Larry Holmes, and Roberto Duran. Freddie had started out as a boxer, and his face showed the result: a cauliflower ear, a nose that looked as if it had been split with an ax. His knuckles and fingers were as gnarled as the weathered bark on an ancient tree trunk. Yet, like Abe, he had an engaging and affable smile. He taught Abe all the tricks of the trade as well as the basics: jabbing, feinting, slipping punches, right crosses, left uppercuts, dodging, weaving. It all paid off.

Abe had his first fight in March 1935, winning by a knockout against Jim Dowling. Abe won his next 13 fights, most by knockouts, before he had two losses. One was to Lou Nova, the other to Buddy Baer, brother of the heavyweight champion Max Baer.

Then, in 1940, Abe knocked out one of the finest heavyweights of the 20th century, Jersey Joe Walcott, a future champion. Now Abe was a contender for the heavyweight title, which was held by Joe Louis.

On March 21, 1941, in Olympia Stadium in Detroit, Abe challenged Louis. He was larger and stronger than Louis, but not as quick and not as skillful. He lasted 13 rounds and lost by a technical knockout. Abe had another shot at the title on March 27, 1942, when he fought Louis again, this time in Madison Square Garden. He lost again by a T.K.O., but claimed that he had risen from the canvas before the referee had counted to 10.

It was Abe’s last fight. He had a good run for seven years, losing 10 bouts and winning 37 — 53 percent by knockouts. He was smart enough to retire before suffering any injuries to his brain, and then wrote an article about his retirement from boxing for Esquire magazine.

Because of his imposing appearance, he had a striking though intermittent career as an actor. In the movie “On the Waterfront” he played a thug in the employ of Johnny Friendly, the dockworkers’ crooked union boss portrayed by Lee J. Cobb. In one scene, Karl Malden, standing in the hold of a ship, is seen urging the dockworkers to rebel against the criminal union that has been keeping them in bondage to poverty and victims of violence and shakedowns. Signaled by a nod from Cobb, Abe throws a beer can that hits Malden’s head. It was a startling scene, and Abe — a Jew — felt uncomfortable throwing a beer can at a character who was a priest.

After “Waterfront,” Abe appeared in the movies “Never Love a Stranger” and the 1962 “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” as well as in several television dramas.

Abe died on Oct. 24, 1969, 11 years to the day after my father died. I am grateful to both men, for while it was my father who introduced me to boxing, it was Abe Simon who exemplified the life of a boxer. I had admired Abe from a distance, but I would never have wanted to follow in his footsteps, never mind that I didn’t wear size-13 shoes.

Jeffrey Sussman is the author of a new book, “Max Baer and Barney Ross: Jewish Heroes of Boxing.” He lives part time in East Hampton.