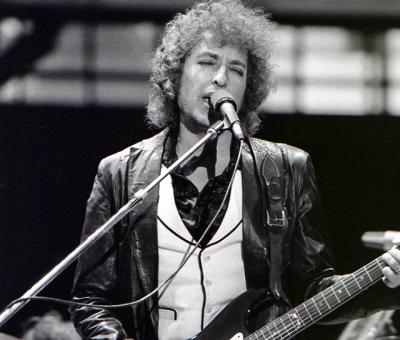

Bob Dylan Was Here, Hiding in Plain Sight

Bob Dylan, always enigmatic, kept the world guessing for 17 days after he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The prize committee honored Mr. Dylan, the first songwriter to receive the award, “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition,” on Oct. 13. Days later, efforts to reach him had not borne fruit, and the world began to wonder if the legendary musician would follow in the footsteps of Jean-Paul Sartre, who refused the same honor in 1964.

Save for a cryptic and quickly deleted reference on his website, it was not until Oct. 30 that Mr. Dylan said that he would attend the Dec. 10 award ceremony in Stockholm, “if it’s at all possible.” At 75, he maintains an active schedule, presently on tour in the South. This week, he wrote the Swedish Academy, which awards the prizes, a letter stating he would not attend the ceremony due to prior commitments.

News of the prize has spurred recollections of Mr. Dylan’s time in East Hampton in the 1970s. Though details are understandably hazy among South Fork residents who encountered him, the artist himself wrote of the period in his 2005 memoir, “Chronicles: Volume 1.”

“My face wasn’t that well known,” he writes, “although the name would have made people uncomfortable.”

“Bob Johnston, my record producer, was on the line,” Mr. Dylan writes. “He was calling me from Nashville and had reached me in East Hampton. We were living in a rented house on a quiet street with majestic old elms — a Colonial house with plantation-shuttered windows. It was hidden from the street by elevated hedges. There was a large backyard and a key to a gated dune, which led to the pristine Atlantic sandy beach. The house belonged to Henry Ford.”

According to a 2008 issue of Deeds & Don’ts, a publication of Cottages & Gardens magazine, the house is on Nichols Lane, landward of the property owned by the late William Clay Ford Sr. Leonard Ackerman, an attorney who represented the artist in a matter — the details of which he does not recall — remembered a hammock hanging in the living room. “They had a problem, some issue I had to resolve,” Mr. Ackerman said. “I had to go to the house. Maybe a zoning violation, but I don’t remember. But I do remember, whoever I spoke to — I believe it was his manager — said, ‘Do you know whose house this is? This is Bob Zimmerman, a.k.a. Bob Dylan.’ ”

Bruce Harry, who grew up in East Hampton and now lives in East Quogue, was a second chef at Roger’s Restaurant, now Townline BBQ, in the early ’70s. “Someone said, ‘Bob Dylan’s sitting in the dining room,’ ” Mr. Harry recalled. “We had other people — I remember Cheryl Tiegs, Marlo Thomas, Craig Claiborne, a bunch of other people.”

“I always try to perfect what I do,” Mr. Harry said, “so I tried to make a perfect order of flounder” for Mr. Dylan. After the meal, “He popped his head in and said, ‘Thank you very much, that was a great meal.’ I was all dirty and greasy, so I didn’t shake his hand.”

The house was rented in the name of Mr. Dylan’s mother, the artist wrote in “Chronicles,” and he was able to maintain a low profile in the town. “I started painting landscapes there,” he writes. “There was plenty to do. We had five kids and often went to the beach, boated on the bay, dug for clams, spent afternoons at a lighthouse near Montauk, went to Gardiner’s Island — hunted for Captain Kidd’s buried treasure — rode bikes, go-carts and pulled wagons — went to the movies and the outdoor markets, walked around on Division Street — drove over to Springs a lot, a painter’s paradise where de Kooning had his studio.”

“Dylan is a master of hiding in plain sight — ‘Don’t bother me, I’m a recluse but I’m here.’ He’s got that going,” said Michael Weiskopf, a musician who fronts the Complete Unknowns, a band that performs Mr. Dylan’s music. Mr. Weiskopf, who lives in East Hampton, was speaking of Mr. Dylan’s long silence on the Nobel Prize, but the observation applies equally to his time in East Hampton.

Mr. Dylan’s description of East Hampton is as poetic as many of his song lyrics. “East Hampton, which was originally settled by farmers and fishermen, was now a refuge for artists and writers and wealthy families,” he writes in “Chronicles.” “Not really a place but a ‘state of mind.’ If your balance had been severely disrupted, this was a place where you could get it back. Some folks there traced their families back three hundred years and some houses dated back to 1700 — there’d been witch trials there in the past. Wainscott, Springs, Amagansett — green expanses — English style windmills — year round charm and a unique kind of light approximate to the woods and oceans.”

In addition to painting, Mr. Dylan composed music during his stay here. In a 2004 interview preserved on YouTube, Jacques Levy, the late director and songwriter, recalled traveling from Greenwich Village to East Hampton, where the two of them spent several weeks writing songs, many of which would appear on the 1976 album “Desire.”

“Sometimes we would go out for a drink late at night,” Mr. Levy said. “After we finished the first song, we went out to a bar. He had this sheet with him, and he’d sit in the corner of the bar. He’d get someone who was sitting there, and said to this person, whoever it was, ‘Would you like to hear a new song I just wrote?’ You can just imagine, can’t you? The person sat there, and he pulled out this lyric sheet, and with great intensity he’s reading this lyric to the person. . . . It was a very funny moment to me.”

Throughout a five-decade-plus career, Mr. Dylan has been nothing if not controversial, and the Nobel Prize announcement has maintained that tradition, setting social media abuzz with shock and no small amount of criticism. Some authors offered praise. Others were disparaging, some of them citing Philip Roth, who was widely expected to be given the prize this year.

“There’s nothing wrong with a musician getting the prize,” said Steven Gaines, the author of books including “One of These Things First” and “Philistines at the Hedgerow: Passion and Property in the Hamptons,” who lives in Wainscott. “But I’m not sure ‘Lay Lady Lay’ is appropriate fodder for a prize for literature.”

Mr. Weiskopf is decidedly with those applauding the Nobel committee’s decision, blasting “all the Mr. Joneses that came out of the woodwork that say he didn’t deserve this. Has Philip Roth had as much impact on the culture? I don’t think so.”

The announcement, after all, referred to the artist’s work within the American song tradition, he said. “How could you argue with that? There are a handful of artists that, maybe, deserve that kind of recognition. These are the people that give peace prizes to Henry Kissinger, so figure that out. I think they finally got something right.”

This article has been updated from the print version to include the news that Mr. Dylan will not attend the Nobel Prize awards ceremony in December.