A Bold Piece

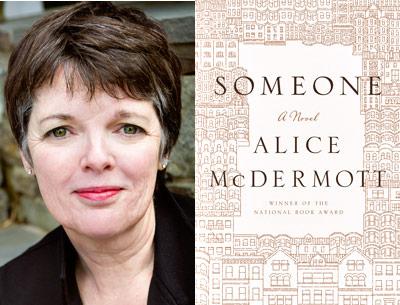

“Someone”

Alice McDermott

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25

The first time I became enthralled with Alice McDermott’s fiction was when I read her second novel, “That Night,” a beautiful and haunting novel about an all-consuming first love set in the 1960s on Long Island. Through a 10-year-old narrator, a neighbor next door, Ms. McDermott brilliantly and sensuously evokes a world of dangerous love, loss, fear, and desperation through the prism of a single summer night.

In “Someone,” through the lens of one woman, she broadens the range of experience to chart the tragedies and milestones of one Irish Catholic family and a neighborhood in pre-Depression Brooklyn.

Marie, the novel’s central character, looks back and pieces together snapshots of her life, from her childhood in prewar Brooklyn as the daughter of Irish immigrants, through the years of her coming of age, her marriage on Long Island raising four children of her own, to her final days in a nursing home.

Feisty, strong-willed, and a keen observer, Marie at a young age is called a “bold piece,” by her mother. On Marie’s wedding night, Tom says, “there’s not much to you, is there.”

“Take it or leave it,” Marie says. And indeed it is her tenacity and compassionate voice that seduce the reader as she reflects upon the joys, dreams, heartbreaks, and sorrows of a life.

What makes this novel timeless and singular is the way in which it slips in and out of time, illuminating a range of pivotal moments in Marie’s life, from a childhood raised by immigrant parents where she witnesses the grief of her best friend’s mother, who dies in childbirth; an account of her own mother’s death; her first encounters with love and heartbreak; her wedding day; the near-death experience of giving birth; to the marvelous and poignant end piece of the book where her older brother, handsome Gabe, early in life bound for the priesthood and to an extent the spiritual center of the novel even after he gives up his ambition, comes to stay with her family on Long Island after being released from a mental hospital, as if plot itself were the way in which our memories live inside us, without regard to coherence or chronology. The incidents of love, loss, and joy reflect off one another like the prisms in a diamond illustrating the many dimensions of a single life.

What on the surface appears to be an unremarkable existence, a life of someone, anyone, Ms. McDermott renders extraordinary through exacting quotidian detail and the poignancy of ordinary relationships. The drama and tension come, as she explained on NPR, “in the most unlikely places,” in the durable relationships between mother and daughter, father and daughter, sister and brother, husband and wife.

While some writers are masters of the broad stroke, Ms. McDermott’s poetic mastery lies in how she boldly renders, illuminates, and elevates small and quiet moments to the quintessential. Who are we, if not defined through the experiences we’ve lived, the novel asks.

In one memorable scene, Marie sits across the booth from her first love, Walter Harnett, who half looks at her and half looks above her head to others coming into the restaurant, and it is transformed into a universal experience — that thrill and dread of falling in love. “In the first throes of my first foray into love’s irrational joys,” Ms. McDermott writes, “I felt both the thrill of his acknowledgement and the hot black rush of shame.”

Or the powerful epiphany she has at the end about her brother:

“My brother was a mystery to me, but a mystery I had always associated with the sacred darkness of the bedroom we had shared in Brooklyn, or the hushed groves of the seminary, or the spice of the incense in the cavernous church, even with his lifelong, silent communion with the words he found in his books. Incomprehensible, yes, but in the same way that much that was holy was incomprehensible to me, little pagan.”

It is in these flashes of intimacy where the magic of Ms. McDermott’s art is on full display: The reader forgets that the indelible lives on the page are fictional creations.

While it succeeds in painting a convincing portrait of one woman’s ordinary life, “Someone” is finally a novel about love. “Who is going to love me,” Marie says to Gabe, who tries to comfort his 18-year-old sister after Walter Hartnett — afflicted with one leg shorter than the other — tells her he won’t marry her because she isn’t beautiful enough for him. “Someone,” he said. “Someone will.” The scene’s poignancy derives from the fact that we witness our own terror and desire for love in its pages.

While in “Someone” Ms. McDermott skillfully delineates the course of love between husband and wife, and parent and child, if there is a central story of love it is the deep and abiding love between a brother and a sister, “different as night and day,” that is evoked most poignantly. From the beginning, when Gabe opens his blanket for his sleepless younger sister after a bad dream, “the way he did everything: quietly, methodically, with a good-natured but stoic acquiescence to duty,” and tells her to say a prayer to keep the nightmares away; when Gabe leads her down the aisle and pulls her into a firm embrace; or at the end of the novel when Marie takes scissors and clips off her brother’s blue hospital band after he is newly released from a psych hospital, their emotional bond is palpable. Though Marie’s brother remains to her an enigma, it is her uncompromising acceptance of him, and his of her, that is most touching. Love is not glamorous or star-crossed in “Someone,” it’s down to earth and necessary.

It is often the quietest of novels, those that allow us to construct a clear structure for examining and framing our own existences, that in the end pierce and endure. “Someone” embodies within its pages the inexplicable dreams and mysteries of all of us.

Jill Bialosky is a poet and novelist. Her memoir, “History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life,” was a New York Times best seller. She divides her time between New York City and Bridgehampton.

Alice McDermott has been a summertime visitor to East Hampton since she was a child.