The Boys on the Bus

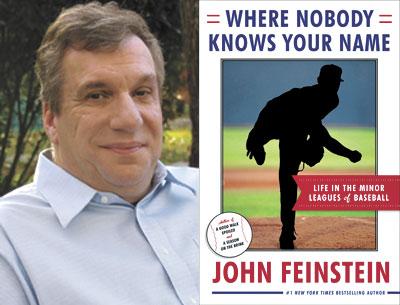

“Where Nobody

Knows Your Name”

John Feinstein

Doubleday, $26.95

“Managing at that level is the worst job there is in baseball,” Buck Showalter, the manager of the Baltimore Orioles, once said of Triple-A ball, where he led a team for four years after having played his entire career in the minor leagues. “Why? Because no one wants to be there.”

Whether it’s limbo for a major league pitcher sent down to rehab a blown-out shoulder, a stopover for a talented prospect on the rise, or purgatory for a demoted outfielder who has drunk the rarefied air of the big leagues and finds himself waiting for another player to be laid low by injury so he can return, “when you’re in Triple-A, you’re ‘this close,’ but you can also be a million miles away,” in the words of John Lindsey, who knows particularly well of what he speaks, having set a record — 16 years — for time spent in the minors before a call-up to the bigs, “the show,” “the life.”

As John Feinstein recounts in his latest book, “Where Nobody Knows Your Name: Life in the Minor Leagues of Baseball,” Lindsey, at 33, was wrapping up a season with the Albuquerque Isotopes when he was called in to his manager’s office one September day in 2010 and stunned by the news that he would be joining the Los Angeles Dodgers. He went to bat 12 times, managing one precious hit, before a pitch broke his hand.

Lindsey, cleverly nicknamed “the Mayor” after the handsome 1960s New York City politician and Mets fan, despite the different spelling, is “a quiet and thoughtful man, very religious and extremely considerate of others’ feelings,” Mr. Feinstein writes, so much so that he was reluctant to tell his teammates that he’d been called up.

All the cliché-heavy “one game at a time” locker room interviews may have left you thinking of athletes as overgrown children, best seen and not heard, but the nine men Mr. Feinstein has chosen to focus on over the 2012 season — besides Lindsey, a designated hitter, there are three pitchers, two outfielders, two managers, and an umpire — are by and large likable and have something of substance to say. The two managers are even admirable in their fair, straightforward treatment of their players and fortitude in handling family tragedies. Charlie Montoyo of the Durham Bulls has a son who undergoes several heart surgeries by the time he is 4, and a daughter of the Norfolk Tides’ Ron Johnson is hit by a car while riding a horse. She survives, barely, but loses a leg.

Lindsey’s case may have been exceptional, but it was also typical, in that he heeded his father’s advice — “Don’t stop until you have to stop” — rather than hang up his cleats to continue online classes with the University of Phoenix, a dreary prospect out-dulled only by Johnson’s stint in his father-in-law’s carpet store in Florida. (This following a significant minor league career and 22 games in the majors.) An opening as a hitting coach with the Kansas City Royals’ Class A team saved him.

“I get paid to go to the ballpark and put on a uniform every day,” he says. “How can I possibly complain?” What’s more, “we’ve got a great bus,” he deadpans one night before a nine-hour trip into the steaming heart of north-central Georgia. “Nobody beats our bus.”

Despite the almost-made-it bitterness that can rival body odor in fouling Triple-A clubhouses, Johnson’s sentiment is echoed throughout the book — an “I’ve always understood that I’m lucky to still be playing” here, an “Anything to get between the white lines” there.

You don’t have to be a baseball nut to appreciate the enthusiasm. Take Doug Bernier, a Californian who went to Oral Roberts University for the top-notch facilities and the scholarship he was offered, not realizing the evangelical nature of the place: The campus’s giant golden hands freak him out upon his arrival; he is reprimanded for going to class in shorts and a T-shirt. “I went to Walmart and found a clip-on tie,” he tells Mr. Feinstein. “I wore it for the next two years.”

After graduation the Colorado Rockies came calling, in a way, offering to sign him as an undrafted free agent, the lowest of the low, for no bonus and $850 a month. “Where do I sign?” was his immediate response.

Although “Where Nobody Knows Your Name” touches on the goofiness we’ve come to expect in the minor leagues — the former Chicago Cubs star Mark Prior being overshadowed by a Lehigh Valley IronPigs “whack an intern” promotion, for instance — if you’re looking for a gritty description of a dying Midwestern city and accounts of struggling players miserably sleeping three futons to a one-bedroom apartment, there’s the recent “Class A: Baseball in the Middle of Everywhere” by Lucas Mann, a young professor of writing who very much puts himself in the story.

This, on the other hand, is serious reporting, and for Mr. Feinstein, the author of “A Season on the Brink: A Year With Bob Knight and the Indiana Hoosiers,” one of the most influential sports books out there, it’s a return to form after “One on One: Behind the Scenes With the Greats in the Game,” which nearly read like a fulfillment of a book contract peppered with score-settling. That form is marked by extensive interviews, with follow-ups sometimes in triplicate, and dogged research. The result is gripping and fun.

Among the injury-hampered trajectories of the nine primary subjects are a few “name” players, too: Scott Podsednik, a hero of the 2005 World Series-champion Chicago White Sox, the 100-game-winner Brett Tomko, and the 6-foot-7 Scott Elarton, who won 17 games as a Houston Astro at age 24. (The book comes with a helpful “cast of characters” glossary.)

Outside of the nine, Mets fans will be interested to hear from Wally Backman, the “spark plug” second baseman for the indomitable 1986 team, who in 2012 was managing the Buffalo Bisons, “an ever-present pack of cigarettes on his desk.”

And then there’s John Maine, once the Mets’ number-three starting pitcher, a star of the 2006 National League Championship Series who five years later was pitching in a coed softball league. As he spoke to Mr. Feinstein, he was with the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Yankees (now the RailRiders), and when they finished, he stood up and grabbed a bucket to go fetch baseballs from the outfield and return them for batting practice.

That’s life in the minor leagues.

John Feinstein had a house on Shelter Island for many years, and still visits family there in the summertime.