Celluloid Secrets

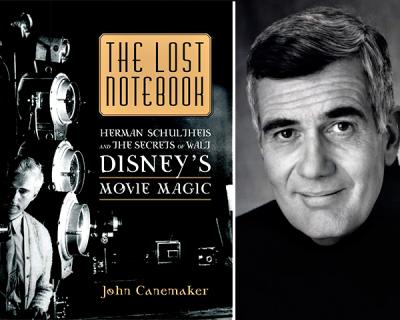

“The Lost Notebook”

John Canemaker

Weldon Owen, $75

“Don’t park your car there, you jackass!” the recluse in the muumuu would call out from a window of her bungalow near Hyperion Avenue in Los Angeles, where the Walt Disney Studio used to be. Hollywood being Hollywood, naturally she had stashed away in a drawer a notebook that amounts to “a Rosetta stone of animation special-effects cinematography,” unlocking “the secrets of how Disney’s first feature-film productions — among the greatest of animated films — were made.”

So writes John Canemaker, the director of the animation program at New York University, in his latest book of animation history, “The Lost Notebook.” The notebook, actually one of five found in Ethel Schultheis’s house upon her death in 1990, was the work of her husband, Herman Schultheis, a photographer, photographic effects engineer, and lab technician whose tenure at the Disney Studio roughly corresponded with its best and most innovative run, from “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in 1937 to “Pinocchio” and “Fantasia” in 1940, “Dumbo” a year later, and “Bambi” in 1942.

Disney’s early artists and animators have long since been celebrated, the author points out, but not so the technical crews, whose work, if not for Schultheis’s obsessive cataloguing of charts, tables, drawings, filmstrips, and photos of obscure equipment, was simply forgotten as technology progressed. Schultheis worked in the Process Lab and the Special Effects Camera Department, where craftsmen “invented and produced imaginative visual effects to enhance the believability of the films’ character animation,” in essence making it up on the fly and coming up with a vocabulary for the new field as they went along.

One famous sequence in “Pinocchio,” which contains some of the most beautiful animation the Disney Studio, or anyone, ever produced, highlights the technological labors: An elaborate “multiplane camera dolly” through Geppetto’s quiet village starts on a bell tower overlooking it. “The ringing bells disturb a flock of white doves, whose flight leads the camera downward” into the streets, Mr. Canemaker writes, where “townspeople begin their day and children head for school as the camera swoops past trees, over rooftops, under an arch, into the main town square, and down a cobblestone street ending at Geppetto’s toy shop.”

The scene lasts 40 seconds and cost $1.8 million in today’s currency.

“The Lost Notebook” is a big, handsome coffee table book, allowing for a complete reproduction Schultheis’s fifth notebook and his documentation of the painstaking work behind such artistry. The production of “Fantasia” is documented in even greater detail.

Mr. Canemaker describes the notebooks as time capsules, Schultheis’s meticulous scrapbooking as the invaluable work of an unintentional historian. (All of his notebooks are in the Walt Disney Family Museum at the Presidio in San Francisco.) But the book is just as much the story of an immigrant striving to make it in the movie business.

That he was an outspoken and opinionated self-promoter hurt Schultheis, though you might think the opposite in Tinseltown, and so did the fact of his multifarious skills, from the camera to the lab, from lighting to sound recording, in an industry that put a premium on specialization. What’s more, hailing as he did from Germany, in the lead-up to America’s entry into World War II he came to be viewed with increasing suspicion, and any number of times was thought to be a spy.

One of his main jobs for Disney entailed wide-ranging travels to take still photos for researchers and artists to use in their work, and away from the studio he kept the shutter snapping, taking untold thousands of shots, the most lasting of them revealing L.A. as it was in the late 1930s — not the glamour, but the working-class side: picnickers in the shadow of a forest of oil derricks, an Asian greengrocer amid her stacks of produce, stable hands taking a break, a young African-American in a bellhop’s uniform selling hats for 88 cents. They’re now being catalogued at the Los Angeles Public Library, which is making them available on its website.

Whether it was fueled by his outsider’s difficulties in assimilating to America and landing a foothold in its exclusive entertainment biz, or simply by his passion for archaeology, just one of his many avocations, is impossible to say, but Schultheis’s wanderlust never abated. In 1955, a plane deposited him in Central America and, carrying two cameras, a pocketknife, and not much else, he strode into the jungle. His scattered bones were found a year and a half later.

Not a pleasant ending, but the stuff of movies.

John Canemaker won an Academy Award in 2005 for his animated short “The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation.” He lives part time in Bridgehampton.