Chasing the Unicorn

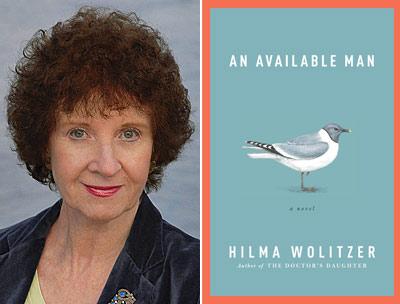

“An Available Man”

Hilma Wolitzer

Ballantine, $25

“The universe is offering you a gift. Claim it.” This is the urgent imperative put forward by a friendly psychic advising the skeptical and reluctant Edward, a widower and the protagonist of Hilma Wolitzer’s engaging new book, “An Available Man.” Edward, whose beloved wife, Bee, has recently died and left him lonely and bereft, ultimately struggles to find a way to claim the gift: a second chance in life, in love.

Those of us who have lost a spouse (and those who have not) will identify with the great stalled tide of grief that engulfs and isolates Edward at the novel’s beginning. Edward’s situation is extreme, but Ms. Wolitzer’s style is restrained, economical, spare, yet canny. She sets her narrative in the conventional flow of life, then skillfully plumbs the sudden, slanting depths. The first time we encounter Edward, he is ironing his dead wife’s blouses, as if pressing memories of her living flesh from the fibers of her clothing.

This portrait of an ordinary person who has suffered an extraordinary loss reveals Ms. Wolitzer’s fine skill in drawing a character who is not exceptional, or even intriguing, yet sympathetic. This is a kind of old-fashioned chivalric tale — Edward is a bit restrained in the fast-moving digital world. He is not “old old,” he is 62, a high school biology teacher, thoughtful and trusting, but a scientist, a naturalist. Edward isn’t conversant with the world of social media, of Facebook or Twitter. When he talks on the phone, he’s usually on a landline (answering machines and even a Rolodex are mentioned), though caller ID, of course, cellphones, and e-mail are in evidence.

Thus when a personal ad is placed on Edward’s behalf, it is published in The New York Review of Books, in old-fashioned newsprint. Responses from potential dates arrive in old-fashioned letter form — via the U.S. Mail.

This plot advances on the title’s seemingly cliched assumption — if a man is widowed or single, he is immediately fair game, “available” to the hordes of desperate single women eager to entrap him.

In fact, this story of a suddenly single, deeply mourning male set adrift in an alien milieu of busybody matchmakers, watchful female family and friends and the assertive widows and other female hopefuls who follow him, breaks free again and again from stereotype, from an old-time movie plot, and illuminates the virtues of its guileless, passive hero — and the saving graces of a few of the ensemble of women.

Ms. Wolitzer does not riff on or refer to the solid statistics that show that, in fact, it is men who are the ones eager to marry immediately after the loss of a partner, and that many women “go rogue” after a spouse’s death — loving the freedom from caretaking and convention, they do not marry again or “come in from the cold.”

The women in “An Available Man” remain mostly cheerfully hetero-conventional in this regard, except for three misfits, women who do not slide easily into the too-familiar patterns. One is Edward’s stepdaughter, who fears abandonment (because of “bad father” issues) and keeps choosing Mr. Wrong. Then there is a silvery sylph who long ago left Edward standing at the altar, a jilted bridegroom. She is hardly conventional, a woman who breaks vows and breaks hearts, a fugitive from love who also endlessly seeks love. She is portrayed as nearly pathological, certifiably crazy — the opposite of Edward’s great lost earth mother love, Bee. (Bee’s name calls up both the essence of steadfast “to be,” existence, and also nature’s busy winged pollinator.)

The elusive female is named Laurel, as in mythology, a hotly pursued beauty who is turned into a tree, inaccessible to all human lovers. She’s also a Lilith figure, the one who refuses to “lie under” Adam and leaves the Garden to Eve, to the “male gaze.” Laurel is the unknown, who keeps the story of Edward from becoming too easy and superficial: a last chance romance.

In contemplating Laurel, the reader begins to realize that despite all of the narrative attention paid to Edward, this is not so much the story of a lonely widower as it is a compelling subtext or sub-story of women’s complex alternative lives and careers — post-grief, post-sexual revolution, post-knee-jerk male dominance.

There is a third female character who is also a kind of misfit, but less darkly drawn than the other two, and finally transcendent. This is Olga Nemerov, a restorer of museum tapestries, a scientist of the artistic past, of history, of the narrative itself. Olga is also the “restorer” of Edward. She is positioned somewhere between the Eve of Bee and the renegade rebel of Laurel; she is an independent woman, a worker, a clearsighted no-nonsense soul, a lab rat like Edward and rescuer of his unicorn-like soul.

Her independence compels her to reject Edward (as he rejects her) at a blatantly obvious matchmaker’s dinner party early on in the novel. She insults him, acts like a “bitch” (as she later admits) to his “clueless prick” (his description). But after a few chapters, they land firmly, ultimately, on solid real ground — not so obviously in Eden as in daily life in the great spectacular egalitarian green of Central Park (Ollie’s Garden, as Edward calls it).

If things are summed up a little too neatly at the end of the book, there is still plenty of thinking to be done beyond the last page. Why do we value men over women, why do women fear age, why do they judge each other so mercilessly, why can only a very few connect to their honest power? And why are men still the unicorns of the family romance?

If none of these questions interest the reader, they can indeed be ignored and the entertaining and wise story of hapless Edward heartily cheered on: a man perhaps too good to be true, but truly “available” all the same.

Hilma Wolitzer’s previous novels include “Summer Reading” and “The Doctor’s Daughter.” She lives in Manhattan and Springs.

Carol Muske-Dukes is a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Southern California, where she founded the Ph.D. program in creative writing and literature. She has a house in Springs.